Fleischer Studios (1933-1938), Warner Home Video (July 31, 2007), 4 discs, 540 mins plus supplements, 1.33:1 original full frame ratio, Dolby Digital Mono, Not Rated, Retail: $64.98

Storyboard:

E.C. Segar’s classic comic strip creation fights for love and honor with the aid of spinach and a whole lot of spunk in these brilliant Fleischer cartoons.

The Sweatbox Review:

How odd to finally be writing this review. When one has found the holy grail, what is there to say? How about…. “Yippee!!!!”

This is the one we’ve all been waiting for, after years of lamenting the fact that these gloriously great golden age cartoons were not available on home video. Due to legalities involving the rights to these cartoons, they have never seen an official release, though the same handful of public domain shorts showed up again and again on videotape and then DVD. Seeing the public domain shorts has been enough to excite animation fans who have either vague or no memories of the Fleischer cartoons starring the sailor. Likely any adult person in the civilized world can recall discovering the Sailor in one form or another early on in life, but for many of us the cartoons that we knew as youngsters were color ones, not the splendid Fleischer originals. And as anyone who has watched the Fleischer ones can attest, the Famous Studios and Hanna-Barbera Popeye cartoons just don’t measure up. And don’t get me started on the ones produced for TV in the 1960s!!

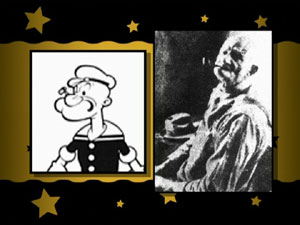

I won’t go into the whole history of Popeye here, but we certainly do need to explore how Popeye made his transition to the big screen in 1933. Popeye had entered the Thimble Theatre comic strip in January of 1929, and within a few short years had come to be the strip’s most popular character. One fan who had come to appreciate the odd magnetism of the Sailor was cartoon producer Max Fleischer, best known at the time as the producer of the Betty Boop cartoons and probably Walt Disney’s biggest rival. Fleischer approached a Mr. Gortatowsky at King Features Syndicate, the cog in the Hearst newspaper empire that owned and distributed Popeye around the country. Mr. Gortatowsky was reportedly amused that Fleischer had any interest in so homely a character, but an agreement was reached. Aside from some money changing hands, the only other parts of the agreement were that King features would have final approval of the initial cartoon’s storyboards, and that the negatives to any resulting films be destroyed in ten years. Thankfully, no one ever followed through on the latter part!!

Popeye was not the only Hearst-owned comic strip property that Fleischer tried out. Little Jimmy, Henry, and The Little King all got their shots later, but none of them lasted beyond that one Fleischer appearance. They all had one thing in common with Popeye, however— they all got their shot in a Betty Boop cartoon. Popeye’s inaugural outing was in a Boop short called Popeye The Sailor in 1933, and despite its official status as a Betty Boop cartoon, the whole show belonged to Popeye. Betty’s only appearance in it was as a Hawaiian dancer, using pre-existing rotoscoped animation from Bamboo Isle. Other than that, Popeye The Sailor established the formula that would be employed dozens of times in the ensuing years. Popeye sings his own theme song, finds Olive being hounded by Bluto, gets bested by Bluto initially, and then eats spinach to gain enough strength to vanquish his romantic rival.

Like all the Fleischer cartoons, directing credit went to Max’s brother Dave, who provided leadership through verbally telling others what he wanted, as opposed to working on storyboards or sketches like directors from other studios. The actual animation direction was done by supervising animators like Seymour Kneitel (Max’s son-in-law) or Doc Crandall. Dave’s influence was all over the cartoons from the studio, however; he insisted that every scene carry at least one gag, and characters were generally kept bouncing to the music even when otherwise standing still. Animation at that time still tended to be from the “rubber hose” school of often non-articulated limbs, and background characters (particularly in the early Popeye shorts) were definitively from the Fleischer school of drawing, including the initial use of very non-Segar-like anthropomorphic animals. Gags were often of the mechanical variety, and usually surreal, utilizing the classic cartoon staples of anthropomorphism and metamorphosis.

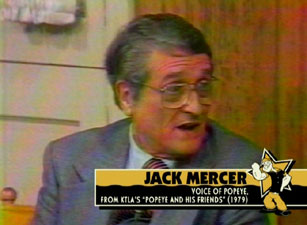

In that first Popeye cartoon, followed by over two dozen more, Popeye’s voice was provided by someone who had done the voice for Gus Gorilla on Betty Boop’s radio show. William Costello, whose vaudeville name was “Red Pepper Sam,” may therefore be credited as the originator of Popeye’s voice, but his involvement came to an end when his ego got the better of him and he demanded a vacation in the middle of production on one of the cartoons. He soon found himself out of a job, and the search commenced for a new Popeye. Though this was initially a difficult proposition, a young in-betweener named Jack Mercer was soon discovered by Max’s brother Lou Fleischer to be doing Popeye’s voice in order to amuse his co-workers. Though there was some reluctance to tie up a promising artist at a studio always looking for new animators, it quickly became evident that Mercer was perfect for the job. He actually had a performing background, as his parents were in show business and had used him in their act before encouraging him to pursue a career in art. Mercer’s new role as Popeye began in 1935’s King Of The Mardi Gras, and it gave him bigger theatrical success than his parents could have dreamed. The comical mutterings he did under his breath became an essential part of the cartoons, giving the Sailor a new layer of character. His role over the years increased such that he provided other voices in the cartoons and became part of the story department. And, for close to fifty years after doing his first Popeye cartoon, he remained the voice of Popeye in his various animated incarnations for film and television.

On the other hand, Olive was played right from the start by the voice of Betty Boop herself, Mae Questel. She immediately found the perfect voice for Olive, based on performer Zasu Pitts. Questel was a versatile performer, and even filled in for Mercer as Popeye on a few occasions. Bluto was another story, as he was voiced by a handful of performers. William Pennell did him initially, but the majority of the time Bluto was done by Gus Wickie, who had ties to Paramount (Fleischer’s distributor) through a quartet he sang with. Wickie died during Popeye’s Fleischer era, though, and others including Mercer and Pinto (“Goofy”) Colvig did turns before Jackson Beck took over the role for the next few decades starting in the 1940s.

Though Fleischer began doing his Color Classics series in 1934 (with Poor Cinderella, starring Betty Boop), all of the single reel Popeye cartoons were done in black and white. The Fleischers, however, did do three Popeye two-reelers in color, with the third of these coming out over eight months before the Fleischers’ first feature, 1939’s Gulliver’s Travels. Those color Popeyes were seen as experiments to see whether the studio could pull off a feature film, and to this day they are seen as masterpieces far more than the resulting features. (Those would be Gulliver, plus 1941’s Mr. Bug Goes To Town. Aside from the Popeye ones, the only other two-reelers that the Fleischers did would come out in the Aprils of 1941 and 1942— Raggedy Ann And Raggedy Andy, and The Raven.) The first two Popeye two-reelers appear on this set.

The DVD set starts out with a disclaimer explaining the obvious (especially to those that have seen the same disclaimer on other cartoon sets from Warner)— that the cartoons presented in the set are a product of their time, and that modern audiences will find that the cartoons’ contents consist of some stereotypes that would be considered offensive today. The point was brought home as I watched Strong To The Finich with my daughter, and she asked why the children in the cartoon were playing with a monkey. In fact, that character was a caricature of an African American child. Yes, this did spark a good dialog between daddy and daughter. You will also see depictions of aboriginal Americans in I Yam What I Yam and Big Chief Ugh-Amugh-Ugh.

We have all seen the public domain Popeyes appear over and over again on cheap tapes and DVDs, so you may be wondering just how many appear on this set. By my count, there are six titles that fall into this category (Little Swee’Pea, I’m In the Army Now, I Never Changes My Altitude, The Paneless Window Washer, and the first two two-reelers, Popeye Meets Sinbad and Popeye Meets Ali Baba). That leave 54 cartoons on this set that most of us have not seen ever, or at least in the long time since they last appeared on television. With sixty cartoons on the set, this is a good match for Warner’s Looney Tunes sets.

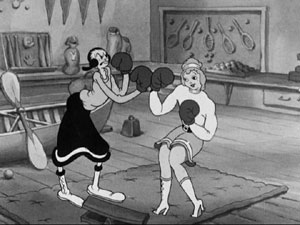

The formula seen in these cartoons is often noted— I have done so myself earlier in this review; but it is worth noting that many of the cartoons do break the mould. Bluto was not always Popeye’s foe, for example, with a trapeze artist being Popeye’s adversary in The Man On The Flying Trapeze. In Strong To The Finich, there is no enemy per se, as Popeye visits a group of children in Olive’s care (here, by the way, Olive is not being voiced by Mae Questel) and tries to convince them to eat spinach. Shiver Me Timbers sees Popeye, Olive, and Wimpy alone on a ghost ship. Choose Your Weppins has no Bluto, but Popeye does battle a crook (who has escaped from Constable Wimpy) instead. Popeye fights only wild animals in Wild Elephinks. Olive actually does some fighting of her own in Never Kick A Woman, where she takes on a pretty “Fleischer girl.” There are a couple of clip cartoons in this set, but even they come off as unique. The Adventures Of Popeye features a live action sissy boy being picked on by a bully, until Popeye comes to life and inspires him with a selection of his best scenes. I’m In The Army Now sees Popeye and Bluto bragging to a recruitment officer about their past battles. A particularly novel cartoon is Football Toucher Downer, where Popeye, Olive, and Bluto appear as children.

The fickleness of Miss Oyl is legendary in these cartoons. She typically starts out with either Popeye or Bluto, but always ends up with Popeye…. Well, almost always. In Barnacle Bill, Popeye proposes to Olive, but she professes that she loves Bluto (renamed Bill for this cartoon to fit the song Olive sings). After seeing Bluto beat up by Popeye, Olive agrees to marry Popeye; but Popeye is disgusted with her, and leaves in a huff. She then proclaims that she may have already worked her way through the navy, but there’s still the army!

The cartoons generally dealt with Popeye, Olive and Bluto, with Swee’Pea, Eugene The Jeep, and Pappy coming in later. Swee’Pea was particularly helpful to the writers, as it gave Popeye someone else to save, as well as other plot variations. In this set, you can see Popeye protect Swee’Pea in a factory in Lost And Foundry, or watch Bluto and Popeye fight over who can best amuse Swee’Pea in I Likes Babies And Infinks. Some Popeye fans have a liking for the 1960s television cartoons only because they made greater use of the comic strip’s vast roster of characters. However, if you look closely enough, you may get the odd glimpse of another Thimble Theatre denizen popping up in the Fleischer cartoons. Olive’s mother shows up briefly in The Man On The Flying Trapeze, and someone who looks suspiciously like Olive’s brother Castor Oyl appears in The Spinach Overture.

The cartoons prominently featured spinach, with only an early exception or two, which was in contrast to the strip, where Popeye initially gained his strength from petting a whiffle hen, and later just seemed to be strong all the time with hardly a mention of spinach. In the cartoons, though, there was no end to what spinach could do for Popeye. Aside from making him super-strong, he could become a super fire-fighter, dancer, or piano player (such as seen in The Spinach Overture).

A fine innovation that Fleischer introduced in these cartoons was the use of three-dimensional backgrounds. A set would be constructed on a turntable that could be spun in front of a camera. The resulting background plates would then have cels placed in front of them and re-photographed, allowing the characters to move across real live backgrounds designed specifically for them. This obviously gave the cartoons a new sense of realism, though this worked to varying degrees in the various Fleisher film series. Generally, they worked very well indeed in the Popeye films. Examples include street sets in For Better Or Worser and Little Swee’Pea, and a delightful carnival in King Of The Mardi Gras.

Watching these cartoons is an absolute delight. Though there is an established formula, it is changed often enough to keep the proceedings from ever getting stale, and the cartoons are expertly directed. Even watching so many in a row, I never tired of them. Somehow, they always seem to be the perfect length, and the gags never grow tiresome. As Michael Barrier notes on this set, Popeye was a perfect match for the eccentricities of the Fleischer studio. These are cartoons at their finest, and they are finally here on DVD for us to enjoy and to share with the next generation.

Is This Thing Loaded?

It would have been enough for many of us just to see these great cartoons coming to DVD for the first time, but Warner did the honorable thing and jazzed up this set with a heaping helping of bonus content almost as impressive as what they have offered in their Looney Tunes sets. Very little goes uncommented on in these special features that look at Popeye himself, all aspects of the cartoons, and even the birth of animation. The only thing missing are some stills galleries.

The first extras to be encountered are the numerous Audio Commentaries. Each disc includes fifteen cartoons, and the first disc alone has eight commentaries, followed by seven, four, and three commentaries on the remaining discs. An eclectic selection of speakers is included, including standbys Jerry Beck and Michael Barrier, as well as Paul Dini, John Kricfalusi, and others. Barrier also provides excerpts from audio interviews that he recorded in years past with those who worked on the cartoons. Each commentary has something to offer, and provides the perfect excuse for sitting through each cartoon again.

Disc One has the largest documentary on the set, I Yam What I Yam: The Story Of Popeye The Sailor (43:23), an excellent piece examining the birth of the character and following him in his many screen incarnations. Such notables as writer Jules Pfeiffer, King Features’ Frank Caruso, cartoon historians Jerry Beck and Steve Stanchfield, animator Eric Goldberg, and many more guide us through the history of comic strips, the birth of Thimble Theatre, and the real-life inspirations for Segar from his home town. Jack Mercer even appears in the form of a 1979 interview segment. Narrator Tom (“Spongebob”) Kenny also discusses the other cartoon versions of Popeye through the years, as well as the Robert Altman movie.

Each disc also has two Popeye “Popumentaries,” which are largely extensions of the main documentary, except that some of these are narrated instead by voice legend Gary Owens. On Disc One, Mining The Strip: Elzie Segar And Thimble Theatre (8:39) goes into more detail in regards to what made Thimble Theatre so brilliant, and contrasts its qualities with what was emphasized in the cartoons. This featurette reveals that Segar died at only 44 years old, just nine years after creating Popeye. Me Fickle Goyl, Olive Oyl: The World’s Least Likely Sex Symbol (4:21) further examines the relationship that Olive had with her two leading men, with comparisons again made between the comic strip and cartoons.

The last items on Disc One are three silent cartoons from the earliest days of filmed animation, under the umbrella title From The Vault: Colonel Heeza Liar At The Bat, Krazy Kat Goes A-Wooing, and the Mutt And Jeff cartoon Domestic Difficulties. One really may wonder what these are doing on the set, but they are placed in context better when one sees the first bonus feature on Disc 2, Forging The Frame: The Roots Of Animation 1900-1920 (31:00). Filmmakers and animators like Terry Gilliam and Ray Harryhausen are joined by animation historians such as Leonard Maltin and John Canemaker to discuss the origins of animation. They cover topics such as the zoetrope, Winsor McCay, early special effects techniques, puppet animation, and the innovations of Bray and Hurd. They get into some of the early cartoon series, which is where the “From The Vault” selections come into play. This makes a great primer for anyone interested in learning more about how animation got its start, and once they discuss the contributions of Max Fleischer in this context, its inclusion in this set feels right.

Disc Two’s Popumentaries include a character profile in the form of Wimpy The Moocher: Ode To The Burgermeister (4:31), where his role in the strip and the cartoons is described; and Sailor’s Hornpipe: The Voices Of Popeye (9:30). It is here that Billy West, Jerry Beck, and others lay out the contributions of Costello and Mercer with interesting commentary. They also identify the other voices heard in the Popeye cartoons, where Mae Questel, radio “Popeye” Floyd Buckley, and Harry Foster Welch filled in when needed.

Disc Two’s From The Vault selections are Earl Hurd’s Bobby Bumps Puts A Beanery On The Bum, Felix The Cat’s first appearance in Feline Follies, and Fleischer’s Out Of The Inkwell short The Tantalizing Fly.

The third disc does not have a longer documentary, but it does have two more Popumentaries. Blow Me Down! The Music Of Popeye (10:02) looks at the Popeye theme written by Sammy Lerner, and the New York and jazz scene influences on the music in the shorts. Popeye In Living Color: A Look At The Color Two-Reelers (5:46) examines the color Popeyes more closely. Moving on from there, the From The Vault selections this time around include six more silent Out Of The Inkwell shorts: Modeling, Invisible Ink, Bubbles, Jumping Beans, Bedtime, and Trapped.

Disc Four opens with some trailers for the fifth Looney Tunes DVD set and Superman: Doomsday. More trailers are selectable from a trailers menu on the disc, including Wait Till Your Father Gets Home, Smurfs: Season One (since reduced to a partial season two-disc set), Space Ghost/Birdman/Droopy, and Tom And Jerry Spotlight Collection Volume 3. The Popumentaries on Disc Four include two more character examinations. Me Li’l Swee’Pea: Whose Kid Is He Anyway? (3:47) answers the question of Swee’Pea’s origin. Et Tu, Bluto? Cartoondom’s Heaviest Heavy (4:41) once again contrasts the comic strip and cartoon versions, while skirting the very important “Bluto” vs. “Brutus” question. This last discs’s From The Vault selections are three more Out Of The Inkwell cartoons (A Trip To Mars, Koko Trains ‘Em, and Koko Back Tracks), as well as Let’s Sing With Popeye, a “follow the bouncing ball” cartoon that features Popeye’s theme song and animation from Popeye The Sailor.

The audio commentaries and Popumentaries are selectable individually from their own Special Features menus, or also by selecting icons beside selected shorts on the shorts listings.

Case Study:

I love the design of this set. This is how classic cartoon collections should look: understated, clear, and with character art modelled after what is actually seen in the cartoons. The artwork by Stephen DeStefano is perfect, even if it is mainly taken from past work he did for the King Features style guides.

The discs are stored in the overlapping format in a digipack, cradled in a slipcase that is not as sturdy as the Woody Woodpecker set but is reasonably durable. Artwork on the slipcase is embossed, giving it more of that Popeye “punch”. Inside the digipack, there are complete cartoon listings, with detailed information on the commentary participants as well as listings of the special features on each disc. Discs are single-sided and all carry character artwork. The single insert in the package is an advertisement for Popeye brand spinach, with recipes and a coupon.

Ink And Paint:

I really couldn’t be happier with how these cartoons look on DVD. They generally are quite sharp and amazingly clear, with minimal dust or other physical artefacts. One must keep in mind that these cartoons are seventy years old, and when you consider that, they look downright great. The odd bit of print damage may show, and some of the shorts do flicker, but to me that is to be expected. Compared to all those public domain cheapies, these look fantastic. I was particularly amazed by the color two-reelers, which are miles ahead of the muddy prints I was accustomed to seeing. The new restorations are simply stunning in their clarity.

Scratch Tracks:

Only the original English mono track is available here, which likely will suit cartoon fans just fine. It is hard to imagine anyone wanting the studio to fiddle with surround sound on these things, or replacing Jack Mercer’s famous depiction with a French or Spanish voice actor. Anyhow, the soundtracks have cleaned up nicely, with no significant hiss or distortion.

The music in these cartoons is very strong, as it should be. As the cartoons were initially distributed through Paramount, the Fleischers had access to the entire Paramount music library, and they could even use songs that were in current movies. When a specific tune was called for, there were also songwriters employed by the studio to create charming ditties to accompany the plot of the cartoon. The background scores were also top calibre, often featuring a distinctive urban or jazz feel.

English subtitles for the hearing impaired are also available.

Final Cut:

Simply put, this is the release of the year. The combination of a classic character, a golden age animation studio at its peak, terrific picture and sound restoration, and an abundance of informative bonus features (lacking only a stills gallery with storyboards, etc.) makes this set absolutely essential. You simply cannot call yourself a serious cartoon fan without owning this set. Everything you have ever heard about these cartoons is true. They really ARE that good. Thank you, Warner, for doing right by the Sailor.

| ||

|