Warner Bros. (1929-1931), Bosko Video/Image Entertainment (September 12, 2000), single disc, 95 mins plus supplements, 1.33:1 windowboxed original full frame ratio, Dolby Digital Mono, Not Rated, Retail: $24.99

Storyboard:

The original star of the Looney Tunes series is featured in a variety of vintage cartoons.

The Sweatbox Review:

While we can now enjoy several beautiful Looney Tunes sets from Warner Home Video, appreciators of vintage animation should not limit themselves to those sets. Some truly classic material that has been released in the past by Image Entertainment, even though the presentation may not be the best. The animation section of your favorite DVD retailer would be woefully bereft of older cartoons if not for the fine folks at Image. Any budding scholar of animation history would do well to purchase their Cartoons That Time Forgot series (in partnership with Kino), The Complete Uncensored Private Snafu (with Bosko Video), The Puppetoon Movie, or their discs featuring Bosko himself. Bosko’s place in history is so significant that the producers of this collection named themselves “Bosko Video”.

Bosko was the star of the very first cartoons distributed by Warner Bros., beginning in 1930. He came about due to the confluence of events that included the changing fortunes of two friends of Walt Disney, the advent of sound in motion pictures, and the fortunate misperception of a fellow who made title cards.

The Bosko shorts were created by the team of Hugh Harmon and Rudolph Ising. Harmon and Ising were early associates of Walt Disney in his Kansas City days, and they continued with him on the Oswald and Alice series when Walt moved to California. The pair later parted with Walt, who was fired from the Oswald cartoons despite being Oswald’s creator. Harman and Ising stayed on with the Oswald producers until Universal Studios in turn cut those producers out of the picture and set up their own studio with Walter Lantz. Harman and Ising, perhaps seeing how their fortunes had hinged on those of the producers, then decided to take a lesson from Disney and climb as close to the top rung of the ladder as they could. They teamed up to be producers of their own series of cartoon short subjects. Thus, the fortuitously named team of Harman-Ising was born.

At the same time, Leon Schlesinger was looking for a new line of work. He was the founder of Pacific Art and Title, and had recently helped to finance the production of the first “talkie”, 1927’s The Jazz Singer. As Pacific’s main line of business then was in producing dialogue cards for silent pictures, Schlesinger thought he would soon be unemployed. In fact, Pacific continues to thrive today, doing work on film restorations (Star Wars Special Edition, Wizard Of Oz), and new artwork for films like the Matrix series. Nevertheless, at the time Schlesinger thought it appropriate to look for a new way to make his fortune.

Based partly on the help he provided with The Jazz Singer, Schlesinger was pals with the Warner Brothers. Jack Warner gave him the idea to produce sound cartoons, and Schlesinger had just happened to have come into contact with Harman and Ising, who were having trouble selling their Bosko character.

Bosko was Harman-Ising’s first creation, a being that was originally of uncertain species. Ising reportedly once stated that Bosko was “an inkspot sort of thing”. For an “inkspot”, it had a certain similarity to a well-known mouse who had debuted in 1928, minus the big black ears. Back in those days, it was common to see characters drawn in similar ways. The Van Beuren studio was notorious for swiping Mickey Mouse’s look in their Aesop’s Fables cartoons, for example, although it could be argued that Mickey himself looked somewhat similar to his predecessor, Felix The Cat. Disney even stated that the character design in his early silent shorts was actually inspired by Paul Terry’s early silent (pre-Van Beuren) Aesop’s cartoons (with a Felix look-alike or two also lurking in the Alice shorts), so one should not be too quick to judge.

Bosko’s cartoons, like Mickey’s, were marketed strongly on the benefit of containing sound. Schlesinger further told Warner Bros. that the Boskos could use music from WB’s own music library, an early example of cross-promotion (as well as a money-saver for the shorts). While the early Boskos did indeed use Warner music, the practice would reach its height in the Merrie Melodies series.

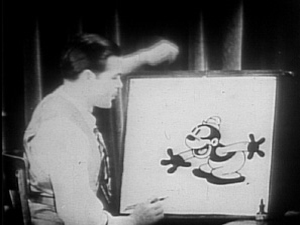

Harman-Ising had made a short pilot film, never released to the public, called Bosko The Talk-Ink Kid. This pilot relied on the early toon tradition of mixing animator and drawing, as the viewer watches Ising draw Bosko. Bosko then takes on a life of his own, all the while existing on the artist’s drawing paper. He is seen dancing, playing piano and singing, before being taken up by Ising’s pen and dropped back into the inkbottle. Fortunately, this already-quaint device was dropped when the regular shorts went into production, starting with May 1930’s Sinkin’ In The Bathtub.

Bosko went on to star in 38 theatrical Looney Tunes cartoons. The name of Looney Tunes was chosen by Harman-Ising as an obvious riff on Disney’s Silly Symphonies. When the similarly-named Merrie Melodies series was begun just as Bosko’s shorts were being prepared, duties were split so that Harman stayed on Bosko while Ising took on Merrie Melodies. During his run, Bosko soon added a Minnie Mouse-ish girlfriend, Honey, and a dog named Bruno.

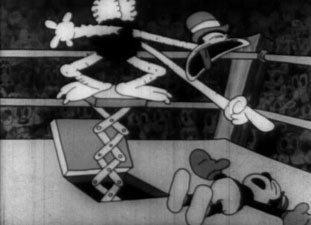

The Bosko shorts featured animation somewhat typical of its day, often by future directing legend Isadore “Friz” Freleng. The limbs of the characters had a rubber hose element where placement of elbows and knees were often difficult to ascertain. Bosko, Honey, and other players stretched, lost their heads, and broke into pieces in the course of a cartoon. Notice that I avoid the term “story”, since the shorts tended to feature a string of events that one would be hard-pressed to describe as a narrative.

Bosko’s rights were retained by Harman-Ising when they left the studio in mid-1933 due to a dispute with Schlesinger over costs. They retained ownership of Bosko, which forced Schlesinger to not only hire new directors but also to have new characters created. Warner Bros. had lost Bosko; but they were soon to gain (after some false starts) Bugs, Daffy, and more.

And what of Bosko? Well, he turned up in 1934, along with Harmon-Ising, at MGM. In keeping with the Silly Symphonies “homage”, Harmon-Ising’s cartoons now appeared under the banner Happy Harmonies. Bosko’s look there evolved substantially until he was quite recognizably a young black boy, which was consistent with his speech patterns in the early Warner Bros. shorts. After a handful of MGM cartoons, Bosko fell into obscurity…

…until appearing in a remarkable episode of Tiny Toons called Fields of Honey, in 1990. Here, Babs Bunny was elated to find that old-time Warner Bros. cartoons did have a female star. This made Bosko take a bit of a back seat, but he did appear. The episode manufactured a backstory about Bosko and Honey disappearing from Warner Bros. cartoons due to the advent of color, rather than a money dispute. But then, Bosko and Honey were also presented as being real, so what can you expect? If you want a real history lesson, read a book.

Speaking of which, I would like to cite my main sources for the above history. Leonard Maltin’s Of Mice And Magic is required reading for all toon buffs, while Steve Schneider’s That’s All Folks is a beautiful coffee table book which presents the history of Warner Bros. animation.

Uncensored Bosko Vol. 1 presents 13 theatrical Bosko cartoons from 1930 and 1931, plus the 1929 pilot. Oddly, they are not presented in chronological order, but they are easy enough to select individually from the menus. The total runtime is 96 minutes. A breakdown of the individual titles follows:

Bosko The Talk-Ink Kid (1929) pilot – see above for info

Congo Jazz (1930) – Hunter Bosko battles a tiger and monkeys before joining into a jungle musical revue with numerous animals and some hula-dancing trees.

Big Man From The North (1931) – Bosko is a Mountie in the frozen North who battles the elements in order to bring in a fierce criminal with the help of his dog team and some big, rubbery pistols. He finds space in his schedule, however, to whoop it up with Honey in a saloon. The villain here bears a remarkable similarity to Mickey Mouse’s Pegleg Pete, including peg leg.

Ups ‘n Downs (1931) – Bosko sells hot dogs that run on the grill, a goat rides a rail while being ridden by several animals including what appears to be Mickey Mouse, Bosko rides a mechanical horse in a race, and somehow it all kind of seems to make sense.

Yodeling Yokels (1931) – Bosko is in the Alps, where he encounters Mickey Mouse-looking bears and saves Honey from drowning. And a mouse golfs in a piece of cheese.

The Tree’s Knees (1931) – Trees frolic with Bosko in this forest cartoon.

Bosko The Doughboy (1931) – Bosko participates in World War I. The subject matter alone makes this one of the more interesting cartoons in the collection.

Bosko’s Fox Hunt (1931) – Bosko and others hunt Mickey Mo— oops, I mean a fox. Mud puddles are dragged to new locations, gun barrels bend and stretch, and other animation conventions get a workout.

Battling Bosko (1931) – Legions of animals come to see Bosko get pounded by a much larger boxer.

Sinkin’ In The Bathtub (1930) – Bosko’s first theatrical short features several examples of wacky cartoon happenings. Bosko plays falling shower streams like a musical instrument, a tub comes to life and prances around the bathroom, Bosko appears naked except for his hat (but apparently has nothing to hide), Honey also appears in the buff, Bosko and Honey share their first kiss, and have car problems.

Hold Anything (1930) – Bosko, now a riveter, again leaves work to woo Honey.

Box Car Blues (1930) – Bosko meets a pig hobo, and we see a mountain pull up its pants.

Ain’t Nature Grand! (1931) – Bosko goes fishing, chases butterflies, and cavorts with nature.

Dumb Patrol (1931) – Bosko makes like Snoopy to fight a Red Baron type, decides to make time with Honey when he gets shot down, and then has to cobble together another plane using a dog and a broom.

Is This Thing Loaded?

This is where the disc really falters. We get nothing at all for extras, in a release that could have benefited from audio commentaries or perhaps a short featurette on where these cartoons and their creators fit into animation history. We don’t even have proper liner notes— just a paragraph each on the back and inside cover from what I suspect was a review of the videotape version.

Case Study:

This disc dates back to Image’s days of using snappers, but this may have come out in a keepcase later.

Ink And Paint:

One could expect that 70-year old cartoons would look less than pristine, and those expectations are met. They are very watchable, but still riddled at times with scratches, film projection wear (notably Battling Bosko), and other imperfections. To me, though, that can be part of the charm of watching old black and white cartoons. A less endearing quality is the murkiness present in some of the cartoons, especially Yodeling Yokels and Bosko’s Fox Hunt. Overall, though, Bosko Video and Image have likely done the best they could. At least the film prints are complete, although some end title cards seem to be from another era. The shorts are windowboxed to various degrees in order to preserve the full image of each cartoon. Unlike Bosko Video’s Private Snafu collection, these cartoons fortunately do not have the Bosko Video “bug” in the corner. This screen capture gives the full image from the DVD. I cropped the others seen in this review for aesthetic purposes.

Scratch Tracks:

The mono tracks have the expected amount of lack of fidelity, although music and dialogue are generally clear. Crackles and hissing are kept to a minimum, though. Again, considering the vintage of these cartoons, the audio is definitely acceptable.

Final Cut:

These cartoons are fluidly animated, and full of energy. For surreal-ness, they fall in-between the Fleischer shorts and Disney. One thing you can say is that these shorts are unpredictable; you never know where they’ll end up or how you will get there. Just how much you enjoy them is somewhat dependent on your interest in animation history, though, since their entertainment value is somewhat less than their contemporary competition from Disney or the later Warner Bros. offerings. They are fun, but are a far cry from exhibiting the beauty of the Silly Symphonies, the personality of Bugs Bunny or the exquisite timing of Chuck Jones. One knock against Harman-Ising is that while their cartoons were usually polished and well animated, they did little to advance the medium. Taken as a whole, their cartoons exhibit a certain same-ness and few “wow” moments. Almost any one Bosko cartoon is enjoyable, but watching many Bosko cartoons can become a trifle dull. Bosko is worth watching, but perhaps in small doses. Still, my “Overall” rating has been influenced by the significance of these cartoons in animation history, and how Bosko Video and Image Entertainment have presented them in the best way possible. This is a must-buy for animation history buffs, a “maybe” for the curious.

| ||

|