Over the years, animator-director Phil Nibbelink has gained a noticeable reputation within the animation community. During his time at Disney, he helped design and animate characters for such films as The Fox and the Hound (1981), The Black Cauldron (1985), The Great Mouse Detective (1986) and Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988). Later, Nibbelink served as director for the features An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991) and We’re Back! A Dinosaur’s Story (1993), in addition to acting as animation director for Casper (1995).

Over the years, animator-director Phil Nibbelink has gained a noticeable reputation within the animation community. During his time at Disney, he helped design and animate characters for such films as The Fox and the Hound (1981), The Black Cauldron (1985), The Great Mouse Detective (1986) and Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988). Later, Nibbelink served as director for the features An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991) and We’re Back! A Dinosaur’s Story (1993), in addition to acting as animation director for Casper (1995).

It was after his experience with the cancelled Cats that Nibbelink chose to create his own production company. With his own animation enterprise, he helmed and animated the features Boogie Woogie Whale Sing-Along (1997), Puss in Boots (1999) and Leif Ericson, Discoverer of North America (2000).

Nibbelink recently participated in a discussion with Animated News & Views’ Josh Armstrong about his latest film, Romeo & Juliet: Sealed With A Kiss (2006). This traditionally animated movie presents a unique vision that was single-handedly brought to life by Nibbelink. Describing the project as a “labor of love,” he explains the journey he took to write, direct and animate the comedic adaptation of William Shakespeare’s classic tale.

Animated Views: How did you become involved with animation?

Phil Nibbelink: Well, I’ve been drawing cartoons ever since I can remember. I’ve always drawn. I’ve filled my closet with sketch pads. I guess in junior high, I bought the Super 8 camera and started animating. I did all sorts of animation using flip books and cutouts and my sister’s Barbie dolls. I was just bitten by the animation bug, and I’ve never turned back.

AV: What animation schools did you attend?

PN: Actually, when I left high school, I went to Italy to learn cinematography at Il Instituto di Stato per la Cinematografia el Televisione. It was a school that was part of Dino De Laurentiis’ studios. I studied film there for a year. Then I came back and went to Western Washington University, where I studied art and film. Afterward, I went to California Institute of the Arts, where I studied the Disney animation program for a couple of years.

AV: Could you share some thoughts regarding your time with Disney?

PN: I was there for ten years. I started in 1978, I think. I started out as a trainee under Eric Larson. From there, I worked my way up, starting out as an in-betweener and then an assistant on The Fox and the Hound before becoming an animator on The Fox on the Hound.

PN: I was there for ten years. I started in 1978, I think. I started out as a trainee under Eric Larson. From there, I worked my way up, starting out as an in-betweener and then an assistant on The Fox and the Hound before becoming an animator on The Fox on the Hound.

That was at the time when Frank and Ollie were just leaving. They had started Fox and the Hound, and they were upstairs writing the book The Illusion of Life. So, we got to see a lot of them. A lot of the old guard were just dying and retiring at the time. It was kind of a ‘changing of the guards’ time for us.

I went on and worked with Andreas Deja on character designs for The Black Cauldron and was on that show for about 4 or 5 years. It seems like forever. Gosh, that was during the time of the takeover. Eisner and Katzenberg came in, and they moved us all out to a little warehouse in Glendale.

We did Oliver & Company. I must say we also did The Great Mouse Detective. I had the great fortune to work with the computers, doing the clockwork mechanism for the Big Ben tower sequence. That was the first foray into computer graphics, back in the days when the most a computer could do was draw lines on a plotter. I was animating to the line art, and the computer drawings were then Xeroxed and painted. That was back in the days when computers couldn’t do full-color rendering or anything like that.

AV: And then you moved on to working for Universal and Steven Spielberg’s Amblin?

PN:I ended up joining the group that went to England to do Roger Rabbit. There, I got to work with Richard Williams and Steven Spielberg. After that, Steven asked Simon Wells and I to co-direct An American Tail: Fievel Goes West.

PN:I ended up joining the group that went to England to do Roger Rabbit. There, I got to work with Richard Williams and Steven Spielberg. After that, Steven asked Simon Wells and I to co-direct An American Tail: Fievel Goes West.

We formed Amblimation, which was Spielberg’s animation company in London. We did quite a few pictures. I spent another ten years then in London, working with Spielberg. We did Fievel Goes West, We’re Back and Balto. We developed Cats forever and ever and ever. Unfortunately, that got shelved.

Ultimately, the whole production got moved to L.A., where it became DreamWorks. So, the core staff at DreamWorks hails from those days in London.

AV: What can you tell us about that production of Cats?

PN: Well, it was originally a London production by Andrew Loyd Webber. I was attached to that for – gosh, I don’t know – six years or something. We developed and developed and developed, and we must have gone through about six or seven different scripts.

PN: Well, it was originally a London production by Andrew Loyd Webber. I was attached to that for – gosh, I don’t know – six years or something. We developed and developed and developed, and we must have gone through about six or seven different scripts.

I think it probably would have gone forward had it not been for Jeffrey Katzenberg leaving Disney, joining Amblin and creating DreamWorks. During all of that big ruckus. Cats kind of got spun out the back door, during the process. I think if that hadn’t happened, we probably would have made Cats. It never got made, unfortunately. But I worked long and hard on it.

We never got as far as nailing a cast down. It was always in storyboard development. We had many meetings with Steven Spielberg and Andrew Loyd Webber, and it was a lot of fun. But it just never quite took off.

In fact, I got separated from DreamWorks to continue working on Cats for Universal. But then, there was the big buyout from Matsushita. We had new management then. The old guard was kicked out. In typical style, when a new guard comes into a studio, they tend to want to bring their own projects and lose the old projects. So I was considered an old project, and out the door we went. That was the end of Cats. We’d love for it to be started up again. But I don’t know if it’s possible.

AV: Why did you decide to start Phil Nibbelink Productions?

PN: I think probably Cats had something to do with that. [laughs] You know, after you work on something for six years and finally have it shelved, it’s kind of frustrating. I thought, ‘Well, you know, I could have made my own film.’ I could have animated Cats six times by myself with the time and money that was spent on development.

PN: I think probably Cats had something to do with that. [laughs] You know, after you work on something for six years and finally have it shelved, it’s kind of frustrating. I thought, ‘Well, you know, I could have made my own film.’ I could have animated Cats six times by myself with the time and money that was spent on development.

I always felt like it might be possible just to do it myself. So, I gave it a try. I did a little half-hour sing-along called Boogie Woogie Whale. It was kind of an experiment for me, of different styles, and allowed me to test how fast I could actually travel by myself. I did the math and figured out that I could probably animate a film all by myself.

I’ve made three feature animated films by myself: Puss in Boots, Leif Ericson: The Boy Who Discovered America and then finally Romeo & Juliet.

People told me, ‘Well, gee, if Leif Ericson had only been on film, we could have sold it for a lot more money!’ So, I bought a film recorder – an Oxberry animation camera that is attached to a high resolution computer monitor. That way, once you’re finished with a frame, you could send it to the film recorder and fire out a frame that’s recorded on 35mm.

I did the math on it. Because it was on a 35mm, I knew that it would have to be fully animated. I looked at how much money I had in the bank and how long it would take for me to do full animation on a film. I thought, ‘Well, if I do characters that don’t have glasses, buttons, fur, hair, clothing, shoes and shoelaces, I probably could go a lot faster.’ I did the math. If I could do a character in two minutes, I figured I could finish the film before my bank account ran out.

I did the math on it. Because it was on a 35mm, I knew that it would have to be fully animated. I looked at how much money I had in the bank and how long it would take for me to do full animation on a film. I thought, ‘Well, if I do characters that don’t have glasses, buttons, fur, hair, clothing, shoes and shoelaces, I probably could go a lot faster.’ I did the math. If I could do a character in two minutes, I figured I could finish the film before my bank account ran out.

You think, ‘What kind of character can I animate other than, say, beans, circles or happy faces?’ I thought, ‘You know, undersea creatures.’ Aqua dynamics being what they are, you could streamline all those animals. Everything from fish to sea mammals are all very featureless, so they could swim through water. So, that’s why I picked them. And I’m a great lover of the California sea lion, and I’m also a great lover of Shakespeare. So, I put together the two things that I love most in the world: seals and Shakespeare. I figured if Bugs Bunny could do opera, seals could do Shakespeare.

AV: Why did you decide to develop Romeo & Juliet by yourself?

PN: I just enjoy working by myself. It’s a pleasure to wear all the hats, everything from the writer to the director to the storyboard artist – well, I didn’t do storyboards, because I didn’t need them. If I write the script, I have the vision in my head.

In a big studio animated feature, you have to be a specialist. You just have to do one character; you can’t do everything. But it’s kind of fun to be able to play all the parts. Animators are like actors, in that it’s fun to do the villain, the hero, the heroine and then the clown. So, to go back and forth is exciting, fun and challenging.

AV: How did you decide to take a more family friendly direction with Shakespeare’s tale?

PN: As opposed to having a double suicide at the end? I was definitely making a G-rated film. I had heard – and I’ve always heard – that there’s a lack of G-rated films.

PN: As opposed to having a double suicide at the end? I was definitely making a G-rated film. I had heard – and I’ve always heard – that there’s a lack of G-rated films.

I certainly could attest as a parent that I’m constantly looking for films that are G-rated. I’ve got four children and their ages are 6 to 13. It’s hard for us to find G-rated films – or even PG, for that matter. You want to get out of the house, but you’ve done the zoo, and you’ve gone to Disneyland. Wouldn’t it be nice to go to a movie, for a change? But it’s all PG-13, which is inappropriate for the little guys. So, I thought I would make a G-rated film to fill that vacuum.

AV: What were some of the reactions you received when you first made your plans public?

PN: I never made my plans public. I just sat in my basement and drew. When it was done, I went around town and tried to sell it, showing it to 800 people. It was picked up by two distributors: MarVista Entertainment takes the film into foreign territories, and Indican Pictures takes it out domestically. We had a Spanish release last summer, during which it played in 32 theaters, I think, around Spain. So, that was a pretty good run.

(Click to enlarge)

AV: Would you break down the process of making Romeo & Juliet?

PN: Well, it was four and a half years of animating. Then, it was another half-year of posting, which means editing and sound. Then, another year of all the mumbo jumbo of trying to sell the film and then completing all the masters.

People don’t realize how much work goes into completing the distributables. In other words, people want to have the thing in PAL and NTSC, and they want it in Betacam and DVD. Plus, they want you to do the DVD menus and the poster. Then, we did the promotional art and all the advertising stuff. So, a lot of work goes into this stuff. I was drawing all of it.

People don’t realize how much work goes into completing the distributables. In other words, people want to have the thing in PAL and NTSC, and they want it in Betacam and DVD. Plus, they want you to do the DVD menus and the poster. Then, we did the promotional art and all the advertising stuff. So, a lot of work goes into this stuff. I was drawing all of it.

Then, every new territory wants a whole new set of deliverables. I mean, the Spanish wanted a Spanish poster. I had to do a trailer in Spanish, so that meant more work, too.

But the four and a half years of just animating – the way that worked was that I had to come up with a process that cut a lot of the steps. I think that if you work in the big studio environment, many of the steps that are taken – like storyboarding, for example – they need to do a storyboard so that you can communicate to a staff of 300 or 1,000 people exactly what this shot is and what it’s about. But in my case, where you have the director, writer and animator all sitting in one chair, I had a very clear vision of how this thing could go.

I think any writer will tell you that characters tend to run away with the plotline. They tell you what they want to do. You write the script with good intentions, and you know your structure. Then, these characters start to come to life, and they dictate the plot basically – not the complete structure, but at least how you get there is dictated by how the characters want to go. You find you write it one way. Then, the characters say, ‘No, no, no. I would never say that! I would never do that! I would go that way!’ If you’re courageous, you let your characters take you where they will.

In the case of Romeo & Juliet, I realized that halfway through, you lose Mercutio. Mercutio is killed halfway through – at least, we think he is. And that’s your sidekick; that’s your clown. That’s your entertainment that’s being killed, basically. So, I slowly had this little character of a goldfish, played by my daughter Chanelle, who was three years old at the time. Over four and a half years, she became better and better and funnier and funnier and quite a character in her own right. So, this character emerged slowly and got up to speed. When Mercutio is killed, Kissy the Kissing Fish just stepped right into the vacuum of the clown and took off and ultimately stole the show.

In the case of Romeo & Juliet, I realized that halfway through, you lose Mercutio. Mercutio is killed halfway through – at least, we think he is. And that’s your sidekick; that’s your clown. That’s your entertainment that’s being killed, basically. So, I slowly had this little character of a goldfish, played by my daughter Chanelle, who was three years old at the time. Over four and a half years, she became better and better and funnier and funnier and quite a character in her own right. So, this character emerged slowly and got up to speed. When Mercutio is killed, Kissy the Kissing Fish just stepped right into the vacuum of the clown and took off and ultimately stole the show.

It was kind of fun to watch that blossom, and it was completely unscripted. I would just take these silly improvs that my little daughter would do. She would say, ‘Babies – PU! I hate stinky babies!’ I said, ‘That’s hilarious!’ So, I just would use it.

She was so little when I was recording her, she would get very impatient and very fussy, and she would only do one or two lines and then jump out of the chair and run away to go play. It’s impossible to work that way, in a big studio situation. But because I have my own recording studio in the basement, I was fine. I would just record the line I needed for that day’s work. Then, she’d run away. I’d go animate. The next day, I’d coax her down with cookies and orange juice, and we’d get another line out of her.

AV: How did you decide the cast for Romeo & Juliet?

PN: Actually, I was developing Romeo & Juliet at the same time I was finishing up Leif Ericson. All the actors that were working with me on Leif Ericson are friends of mine and really super-good actors. I just said, ‘Gee, I’ve got another project here. Would you mind doing that, too?’

See, for the actor to do the voice for an animated feature, it’s quite a quick job. It’s not more than just a few hours in front of the mike to do the whole thing. I think in the case of Mercutio, Chip Albers was such an amazing guy, and he was so into it, that we kept recording and kept recording. He was so funny on the mike that anything that I wrote was just, ‘Forget it.’ He was just much funnier. So, we would just use his improvs. He was having so much fun that we ended up doing it this way. He actually came back several times to add more stuff. We got a good performance out of him, ultimately. In fact, I was spoiled for choice. I had so much funny material, it was hard to edit it down.

See, for the actor to do the voice for an animated feature, it’s quite a quick job. It’s not more than just a few hours in front of the mike to do the whole thing. I think in the case of Mercutio, Chip Albers was such an amazing guy, and he was so into it, that we kept recording and kept recording. He was so funny on the mike that anything that I wrote was just, ‘Forget it.’ He was just much funnier. So, we would just use his improvs. He was having so much fun that we ended up doing it this way. He actually came back several times to add more stuff. We got a good performance out of him, ultimately. In fact, I was spoiled for choice. I had so much funny material, it was hard to edit it down.

AV: What about the voice cast for the film’s Spanish release?

PN: The studio used dubbing. They’ve got their little troop of repertory actors that just step right in and do the voices really fast and then go on to the next movie. Dubbing is quite an industry.

AV: So, you didn’t handle any of that part, right?

PN: No, that was done in Madrid.

AV: What were some of the deleted or abandoned concepts from the film?

PN: Well, when you’re a one-man band, obviously you really can’t afford to take any missteps or have too much reconsideration. I know when I worked on a Spielberg film, I had a multi-million dollar budget. You still try not to do that, but you end up making changes, and they do run into the millions sometimes. I just simply couldn’t afford that.

It’s all about thinking ahead of time. It’s about trying to be very, very smart about everything you do and trying to get it right the first time. There were very few – I think there’s one deleted shot, in a scene where I went down the wrong path from a story point of view and changed my mind. Within that shot, I decided to abandon it and go in a different direction. I think I did that once. Everything else was pretty much straight ahead.

AV: Could you elaborate on that shot you deleted?

PN: It wasn’t really spectacular. At one point, I had scripted that the shark would come back yet again for another attack. When I started to animate it – and by ‘started to animate,’ I mean when I spent a morning on it – I realized that we had just done it. We’ve seen the shark; we’ve killed the shark. Let’s just move on. So, I abandoned that shot and went forward with the story. It was just a small, small deviation.

PN: It wasn’t really spectacular. At one point, I had scripted that the shark would come back yet again for another attack. When I started to animate it – and by ‘started to animate,’ I mean when I spent a morning on it – I realized that we had just done it. We’ve seen the shark; we’ve killed the shark. Let’s just move on. So, I abandoned that shot and went forward with the story. It was just a small, small deviation.

The big deviations came, I think, with the sound, when I had great material from Chip Albers, my daughter Chanelle and also from Michael Toland, who did the Friar. Also, I have to say, the people who played Romeo and Juliet were the husband and wife team of Danny and Tricia Trippett. When you have a lot of great acting, you tend to follow it around.

You know, the sound comes first in an animated feature. So, I did a lot of sculpting with the sound, before I started animating. That’s a very free-flowing and changeable environment. But once you start making all those thousands of drawings, you really have to know where you’re going. You just can’t change your mind too much at all really, when you make that many drawings.

AV: How many drawings did you do for the film?

PN: Well, I calculated that I did 112,000 drawings. Much of the film is on ones, which means a drawing for every frame of film. Some scenes are on twos, but then there are multiple characters that are also animating on twos – you know, all the crowd scenes. On those particular shots, you have many more drawings per frame, because you have multiple characters. So, a lot of work went into this film.

AV: About how many of those drawings did you do every day?

PN: I had a basic benchmark of about a hundred drawings a day. If I did a hundred drawings a day, I could keep on track. In fact, I made it within a month of my original prediction. I was that tight on the math.

PN: I had a basic benchmark of about a hundred drawings a day. If I did a hundred drawings a day, I could keep on track. In fact, I made it within a month of my original prediction. I was that tight on the math.

AV: And it was all done to the current industry standards? The accepted aspect ratio and frame rate?

PN: Yes, it was 1.66:1. As for the frame rate, it’s 24 fps.

AV: And what was the average day for you like, during the making of the movie?

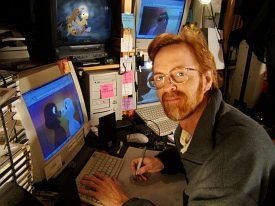

PN: Since it was in my basement, of course, I commuted in my socks. [laughs] Get the kids off to school and then go downstairs. I would work on a graphics tablet, and I worked with Flash. The backgrounds were done on a program called Painter – I guess it’s now owned by Corel.

Flash was used for the character animation. Behind it, I would put a bitmap. Flash is a vector-based drawing program. The computer draws in two ways. It either draws with bitmaps or vectors. A bitmap is where the painting is done like a checkerboard. It understands all the pixels going right across the screen, you know, the top left-hand corner is pixel #1, second pixel over is pixel #2… So, you can get very painterly effects with that.

Then, with the character stuff, I wanted perfect lines that could be blown up on the big screen. That’s hard to do in a bitmap world, especially because I wanted to keep the files small. So, I used Flash, because it draws with vectors. What I mean by that is, the computer understands a line in terms of its start point and end point and one point in the middle that creates the curve. What that allows the computer to do is output the line work to incredibly high resolution, which I would do. I would put out these giant files that would go to the film recorder and those would be shot one frame at a time on film. But, for me, animating vectors keeps the files very small so I can go very fast.

I also used a really interesting program called Anime Studio, which allows you to make a drawing and then put a skeleton into that drawing. You can move that drawing around like a 3-D character. That was used a lot for the crowd scenes and stuff, or sometimes you have an over-the-shoulder shot. The character that is the over-the-shoulder, you just want the heads to turn a little bit back and forth. I would use Anime Studio to animate the back view, and then the character you’re looking at would be done in full Disney-style motion.

I also used a really interesting program called Anime Studio, which allows you to make a drawing and then put a skeleton into that drawing. You can move that drawing around like a 3-D character. That was used a lot for the crowd scenes and stuff, or sometimes you have an over-the-shoulder shot. The character that is the over-the-shoulder, you just want the heads to turn a little bit back and forth. I would use Anime Studio to animate the back view, and then the character you’re looking at would be done in full Disney-style motion.

AV: What would you say was the budget for the movie?

PN: Oh, I’ve been told I shouldn’t tell. But basically, because I paid for everything myself, and I was the only employee, it was very low.

AV: You also composed the music for the movie, didn’t you?

PN: No, there’s a thing called Buyout Music. It’s music that is royalty-free. I would find music that had a good melody, and I would just write lyrics to it and get my children or my actor friends to sing to it.

(Click to enlarge)

AV: What are some of the most memorable experiences you had while making the movie?

PN: Well, I certainly enjoyed the whole process. Although it did take a long time, it was very satisfying work. I would love to do it again. So far, we haven’t broken even, so I’m hoping it will do well on DVD.

But most memorable? I don’t know, nothing really jumps out at me. Let’s see… I guess working with the actors.

AV: How did you find the motivation to complete the movie? Did you ever just say, ‘You know what, I don’t think I’m going to finish it!’

PN: Yeah, that’s always there. You’re fighting fear, frustration and depression. But you’re also egged on by the fact that the film is looking good, and you’re enjoying the work.

PN: Yeah, that’s always there. You’re fighting fear, frustration and depression. But you’re also egged on by the fact that the film is looking good, and you’re enjoying the work.

I knew how long it would take, and I had great support from my wife. I think my wife deserves a ton of credit here, because she supported my madness. Not many wives, I think, would do that. My love and appreciation – I have a lot for my wife, for letting me do this crazy thing. And it is crazy. I can’t recommend it.

I noticed on the internet, a lot of people were saying, ‘Oh, it’s so great to have somebody do this! Boy, this is lighting a torch for the rest of us who always dreamed of doing this!’ Frankly, I can’t recommend it, because it’s a lot of work and not much money.

Like anything in this world, when you create something, there are always the tomato throwers. I’ve had a lot of tomatoes thrown at me. But I’ve had a lot of compliments, too. It’s not like I’m a multi-billionaire, and I bought an island or something after all this.

AV: When you started the project, was there any myth or belief you had that would be changed during the film’s making?

PN: Well, since I had made two before, I kind of knew the routine. I mean, there’s always the tough end. All independent filmmakers say this, that it’s even tougher to sell and distribute the film than it is to make it. I mean, you think you’ve been through a living hell to try to make it. Then, when it comes time to distribute it, it’s even harder.

I think that’s the toughest part – when you have to go out and sell the thing to people. It is a meat market out there. When you go to try to sell your film, you’re standing next to a thousand, two thousand, eight thousand other guys that are trying to sell their movie. It’s a big meat market. All these guys that are the buyers are just bored as hell. They’ve already seen 14 films that day before they get to yours. They look at the first three minutes of it and go, ‘Eh… nah.’ But they go ‘Eh… nah’ to 8,000 films a day, so…

I think that’s the toughest part – when you have to go out and sell the thing to people. It is a meat market out there. When you go to try to sell your film, you’re standing next to a thousand, two thousand, eight thousand other guys that are trying to sell their movie. It’s a big meat market. All these guys that are the buyers are just bored as hell. They’ve already seen 14 films that day before they get to yours. They look at the first three minutes of it and go, ‘Eh… nah.’ But they go ‘Eh… nah’ to 8,000 films a day, so…

It’s not a pleasant experience. But if you fight for your film and continue to show it around, you’ll finally find someone who’s excited about it and wants to take it. They say, ‘Oh, this is the greatest thing I ever saw!’ That’s what you want. You want to find someone who’s excited about your film.

AV: While trying to find distribution, what was your most memorable experience?

PN: We had different screenings. We rented theaters and invited film acquisition executives to all of them. We had our very first on the Sony lot, in a really nice theater. We had organized it with the guards, who had the guest list and everything like that. Well, for whatever reason, the guards lost the guest list and all the executives were turned away at the gates. So, I had a very empty screening room, which was pretty frustrating.

Afterward, we decided to get screening rooms that had no security whatsoever – the main door opened right onto the parking lot. We found screening rooms that were literally on the parking lot. So, we were able to get more guys into the following screenings.

AV: How did Indican Pictures finally come across your film?

AV: How did Indican Pictures finally come across your film?

PN: They were at the very first screening. They were one of the few people that made it into that Sony screening at the time. They liked it and wanted it.

AV: What were some of the ways you helped market the film?

PN: I was doing just about everything. I made the poster. I made a sandwich board of it, put it on my front and my back, and walked around in front of the theater that was going to show my movie the following weekend. I was giving little Xeroxed handouts to all the families – ‘Come see my film next weekend!’

I was doing everything on the internet. You should read some of the stuff in the chat rooms. I don’t know if you ever saw some of that stuff of me and my work when it was just coming out. Animation World Network – you could do a search and see that there’s a number of chats there.

I was trying to get all my friends to help me one way or the other. Also, one of my friends got me into the Best of the Southwest digital film festival, which is every year in New Mexico. I won first place in the animation category and Best in Show, so I got two awards. It was really nice. That’s good, because then we can put ‘award-winning film’ on the poster. In fact, they’ve invited me this year, in October, to go out there and speak. That’s quite an honor.

AV: Animated News & Views’ review of the Romeo & Juliet DVD brings up the color differences between the digital transfer of the feature to the deeper look of the disc’s trailer, which was taken from the film print. What’s the story behind the DVD transfer for Romeo & Juliet, specifically regarding its colors?

PN: The master for the DVD comes from an HD that was created from all the 2K files. That was then bumped down to a Digi-Beta center extraction. Unfortunately, distributors today demand that you deliver an HD master of the film. To telecine film in a HD bay is more expensive than to just bring in 112,000 BMP’s on 15 USB drives and have them dump it to tape. I would have loved to go from the internegative, but I paid for the entire movie myself and had to look for corners to cut.

Whether it’s film or video, there’s always problems. What looks good on one monitor or movie projector looks completely different on another. It’s a moving target. Film has dust and scratches; video has crushed gamma and NTSC legal issues. Personally I prefer film, not just the look but because it’s a 100-year-old technology. It’s low tech and high quality. And as an independent filmmaker, if you run the numbers, you’ll be surprised how cheap film is by comparison to HD.

Whether it’s film or video, there’s always problems. What looks good on one monitor or movie projector looks completely different on another. It’s a moving target. Film has dust and scratches; video has crushed gamma and NTSC legal issues. Personally I prefer film, not just the look but because it’s a 100-year-old technology. It’s low tech and high quality. And as an independent filmmaker, if you run the numbers, you’ll be surprised how cheap film is by comparison to HD.

AV: Sounds as if there were a lot of technical demands. Looking back on the film, what would you say was your largest challenge?

PN: It was all a challenge – absolutely everything. I mean, I was fighting technical problems. I had a film recorder that I was fighting with constantly. I was trying to sort through all the technical crazies there.

The other challenge is artistic. I’m trying to be as good as I can possibly be, and I’m constantly frustrated with my own inabilities to draw a straight line. The financial challenges, the burnout… When I was running at full tilt, the kids would come home at the end of the day, and I would have to be with them and feed them and put them to bed. Then, I would go back to work, after they went to bed, and I would work until two in the morning. That kind of schedule, over many years, wears you thin. I was always operating at the cutting edge of burnout.

But I was always artistically challenged and eager – never bored. I never wanted to quit. I was really excited to run downstairs and get those kids off to school so I could jump back into the saddle and wrestle with this vision. It’s a passion. It’s a labor of love.

AV: Are you ready to jump in and do it all over again? Anything in the pipeline?

PN: While I was doing all the posters and all the deliverables for the individual distributors, I bought a 35mm movie camera from eBay, and I went out and shot a live-action film, again using my children as actors. I even used myself as an actor and got my 12-year-old daughter to film me.

PN: While I was doing all the posters and all the deliverables for the individual distributors, I bought a 35mm movie camera from eBay, and I went out and shot a live-action film, again using my children as actors. I even used myself as an actor and got my 12-year-old daughter to film me.

That film, Windcatcher, will be half-animated. If you know anybody who wants to fund it, I’m currently seeking funding. I’m also working with a friend on a graphic novel, so that’s coming sometime soon.

AV: Do you think you’ll continue to write, direct and animate your films by yourself?

PN: I don’t know. I’m kind of in a period of transition right now, because I would like to see how Romeo & Juliet does before I launch into another epic struggle. Making Romeo & Juliet is comparable to climbing Mount Everest. It’s kind of a life-and-death struggle to the top. I need to catch my breath a little bit.

AV: What advice do you have for anyone who wants to work in animation?

PN: The animation industry is changing now, with 3D coming sort of strong and hot, and 2D kind of almost disappearing. I came from a world where the artist was king. If you could draw, you got a job. The better you could draw, the more money you’d make. So, I’m one of these guys who tries very hard to draw very well. That’s sort of a disappearing art.

It’s being replaced by computer animation. I know how to do computer animation. I have done it. I co-directed the animation on Casper. So, I have done 3D animation and live-action films. I animated the 3D stuff in Windcatcher; I know how to do it. I also enjoy doing this comic book because, again, it’s all about craftsmanship and drawing. In the old days, you’d say, ‘Well, gee, learn to draw! Always learn to draw! Practice your drawing!’ But now, you say to people, ‘Well, learn Maya.’ [laughs] In a way, it’s kind of a lost art form. I feel like a dinosaur!

It’s being replaced by computer animation. I know how to do computer animation. I have done it. I co-directed the animation on Casper. So, I have done 3D animation and live-action films. I animated the 3D stuff in Windcatcher; I know how to do it. I also enjoy doing this comic book because, again, it’s all about craftsmanship and drawing. In the old days, you’d say, ‘Well, gee, learn to draw! Always learn to draw! Practice your drawing!’ But now, you say to people, ‘Well, learn Maya.’ [laughs] In a way, it’s kind of a lost art form. I feel like a dinosaur!

But I don’t know what I would advise animators. I guess animation still is and will always be acting, drama and storytelling. To be a good animator, you have to learn to act. You can certainly take classes and get involved with local theater, college classes and stuff like that. You’ll always need to learn to act, whether you’re a director, a storyboard artist or an animator. You’ll always use acting skills and also pantomime skills, because you want to be able to show how to lift up a heavy object, how to push against a heavy door, or how to communicate without words that you are sad or happy. These are basic scenarios in the art of acting. I look at comic book artists as kind of the last of the great 2D craftsman. I look at them, and boy, there are guys who can draw, and there are guys who can act. The best ones are the guys who can draw and act!

Staging – that’s the other thing, too, that you need to learn. Staging is so important, because you can show a great emotion, but if you cover it by a bush, that’s bad staging. So, you need to learn that. You also need to know film grammar. These are skills that are needed by everybody.

is now available to own!