In the late 1970s and early 1980s animation was, as with the entire movie industry, finding itself heading down more sombre paths than the form had been known for in the past. The in-vogue genre of live-action filmmaking at the time was the fantasy epic, with blockbusters such as Conan, Krull, Clash Of The Titans, Legend and the like competing with animated fare such as The Lord Of The Rings, The Last Unicorn and Fire And Ice, with even Disney’s offerings of The Rescuers, The Fox And The Hound and especially The Black Cauldron darker in tone than the light-hearted fairytales of old. Into this mix came a pair of lower-budgeted, but no less important, films; indeed they have perhaps stood the test of time better than any of those named above.

When Richard Adams first related the story of a burrow of rabbits and their journey across England to safer pastures on long car drives to his two daughters, he had no intention or idea that it would become the basis of one of the most ambitious and multi-layered animated features ever brought to the screen. Watership Down was one of the first animated films I saw (the other at the time was The Rescuers) and my father was fortunate enough to know the film’s editor, Terry Rawlings, so I was able to visit Terry during the editing and see the film come together on the Steenbeck machine – still a cherished memory and probably the basis of my own eventual move into film editing. A few years later, another Adams novel, The Plague Dogs, found its way to the screen from the same team, again under director Martin Rosen. Now, for international viewers (and those lucky enough to have multi-region capability), both of these movies have been given a new chance to shine on Region 4 DVD, especially Plague Dogs, which Australian distributor Big Sky Video has released completely UNCUT for the first time in over 20 years.

WATERSHIP DOWN: 25th Anniversary Edition ORDER FROM EZY-DVD HERE

Packaged in much the same way as Warners’ own Region 1 pressing of the movie, Big Sky’s Watership disc carries the movie in what the sleeve notes is “remastered 1.85:1”, but is in actual fact a 1.78:1 anamorphic widescreen transfer. Compared to Warners’ 1.66:1 LaserDisc of old, it crops a little top and bottom off the movie to bring it closer to the original theatrical presentation, and offers a slightly higher contrast image, if not perhaps as strong as it could be. Picture quality seems to have suffered little, with the movie and extras all bundled onto a single-layer DVD-5, though I have not been able to compare it to the US edition, which I have heard is mediocre at best. Certainly the print is in better, brighter shape than the LD, and audio comes in the form of two-track Dolby Stereo, which sounds as good, if a little more spatial, than the digital mix on the LD.

As with the original book, one might think that a story populated with a fluffy bunny cast would be aimed at children, and while the film continues to receive fairly low censorship ratings, there really is a lot in here that could – and has over the years – give children nightmares. But, in all honesty, they’re the kind of nightmares that I think kids, if not the youngest of children, can handle, and after all, weren’t we all a little bit traumatised by the Wicked Witch in Snow White or the death of Bambi’s mother? Above all else, and taking its lead from the book in which Adams created the most perfectly realised “alternate world” since JRR Tolkein’s Lord Of The Rings, Watership Down is as realistic as animation gets, with on screen death, horrific premonitions of real fear and danger, and primal forces at work in an all-natural setting.

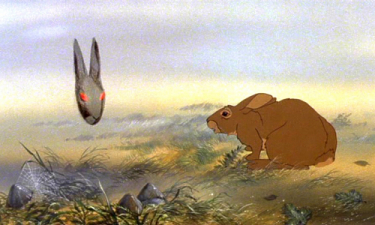

Following a number of rabbits on their long journey from a soon-to-be building construction site warren to the dreamt about country fields that offers them true freedom, the story is expertly written to take into account at least three or four lead characters – Fiver, Hazel, Big Wig among them – all of which have their importance to the group and to the plot. As they face their foes along the way, the real danger lies ahead, in the shape of the bitter and twisted General Woundwort, whose own band of rabbits presents an offer of protection at a terrifying price. Standing with his comrades, and finally within sight of the Watership Down paradise they have been looking for, Hazel leads the rabbits into the final battle against Woundwort’s faction…a battle that steer them all dangerously close to the ever present Black Rabbit Of Death…

Released in 1978, a period that many could call animation’s nadir, Watership Down took many by surprise, not least down to its expert storytelling and provocative themes. Though, by nature of being a screen adaptation, events have to be omitted from the source material, Rosen keeps the important points in, resorting to some character merging and rearranging of proceedings in order to keep them relevant to their place in the screenplay. Most commendably, there is always a feeling of foreboding throughout the film, which is superbly set up in the film’s opening and remains even with the viewer after the credits have rolled. It never reaches the levels of complexity that the novel’s many deep pages does, of course, but Watership Down does that rare thing: adapts a book into a gripping film version while also working completely as a work of its own – indeed it has often led back to the reading of the book again.

The animation, which among today’s CGI eye candy is as fairly rudimentary as they come, holds a charm that reveals a great level of work and attention and none of the cookie-cutter techniques that have marred features supposedly superior in quality than this (you’ll notice not one rabbit looking the same as another, for example). Also beneficial is director Martin Rosen’s live-action background, which lends the film an interesting new approach. Rosen decided to shoot the film in animation as there simply wasn’t another way at the time to faithfully convey the themes of Adams’ book, and the director’s lack of animation training (with all due respect) meant that he was pushing the envelope in the kinds of shots he was asking from the artists, such as longer takes and highly detailed panoramic backgrounds, here rendered in muted watercolors that seem so much more vital in creating the rabbits’ world than CGI or even true live-action ever could.

If there’s anything out there in wider seen western animation that has come close to this book-to-screen version, it’s Don Bluth’s The Secret Of NIMH (whose journey to the screen was no doubt helped by Watership’s commercial success), which also tries to convey different and interesting ideas from its source novel, but that just slides short by trying to dress these themes up with sometimes mawkish moments that stop the dramatic flow. Watership has none of that to worry about, though it is not the po-faced, sorry, sad and depressing motion picture that I may be describing (that would come, in The Plague Dogs). No, Watership Down is, among all its realism, a hugely enjoyable movie, delicately designed to offer its ideas subtly, never hammering the point home, while not shying away from them either (the more violent scenes are handled with all the aggression and blood you might imagine would occur if this was happening for real).

A fair level of criticism has been levelled at the film for its “Bright Eyes” moment, in which Fiver faces a vision of the Black Rabbit for the first time and must confront his brother Hazel’s mortality. For me, apart from all the fuss, it fits in beautifully, and is an overlaid song used to express a haunting mood, rather than having the Black Rabbit sing and tap dance his way into Hazel’s life. Indeed, apart from this pivotal scene, the song does not feature as a recurring motif anywhere else in the film and yet remains as memorable as any of its images, which surely says more about its power than any critic could try and dismantle. Author Richard Adams was himself no big fan, from what I understand, but the song – recorded here and released as a hit record by Art Garfunkel – remains a wholesale part of the film and an important element in its more widespread public identity.

In speaking about the music, I should also make a point of highlighting Angela Morley’s tremendous score, which stays with the viewer long after the film has ended, and always takes me right back to when I first saw Watership Down whenever the orchestra strikes up any one of the number of strong and perfectly suited themes. Such a shame that this obviously talented composer – who apparently wrote the score in just one week – has not been offered much work of any great importance since; the result, unfortunately, of an intolerant world unsympathetic to her personal circumstances. It’s well worth hunting down the hard-to-find official soundtrack CD, though a number of bootleg editions add alternate cues (but you didn’t hear that from me, okay?) and the final release version of “Bright Eyes”.

While we’re on the subject of the film’s soundtrack, I’ll also speak briefly about Watership’s voice cast, which is a veritable “who’s who?” of British acting talent, among them John Hurt, Ralph Richardson, Denholm Elliot, Nigel Hawthorne, Richard Briers as Fiver and a truly mad Zero Mostel as the crazed seagull Kehaar, the closest the film ever gets to a genuine comedy character, but still one who is fairly adult in his language (note the way he tells the rabbits to mind their own business). Needless to say, all do a fine job under Rosen’s direction, especially Hurt, who would reunite with the director for The Plague Dogs and who remains a very fine actor, here carrying most of the heavy dialogue and delivering it with significant understanding and conviction.

Despite being a fairly small independent company, Big Sky have been able to pack Watership Down with a decent heap of extras, some of which seem to be duplicated from the US release, but best of which is an exclusive full-length audio commentary with director Rosen and FilmThreat.com editor Chris Gore. The pair speak with much love and affection for the film, with Rosen on top form as he remembers the production in detail, and Gore keeping mum when the director hits his stride (which is often). Rosen offers a no-punches-pulled approach, reflecting on reading the book, meeting Adams and convincing him it could be made into a film, his jump from being a producer to director, material that was cut and the struggles to pull everything together at several “last minutes”, as well as the reaction to the film and its mistreated use as a “kids’ movie” in the years afterwards. The discussion with Rosen, who reminded me in voice of Marty Scorsese, isn’t terribly scene specific apart from one moment when Kehaar appears and they talk about the casting of Mostel in the role, and doesn’t touch on the subsequent, “softer” TV series version, but as one might expect does contain very intelligent points, leading to one of the most truly insightful commentaries for a film – animation or not – out there

The film’s brilliantly dignified and thoroughly involving theatrical trailer is also included in anamorphic widescreen, and in great print shape, offering up the interesting way that the film was sold to audiences originally. It would be more than fascinating to see how such a film (if even greenlit now) would be promoted today, though this preview is as exciting as they come. Text and stills of the real Watership Down that inspired the locations follow, though there’s nothing on the site as it is today (sadly now with a highway running through it), and the stills are shared two to a page, which makes detail harder to pick out. A “Bright Eyes Loop” adds little, fairly pointlessly running this section of the movie out of context (and oddly not actually on a loop).

A pair of still frame galleries feature a good selection of production photos (with Gordon Harrison mis-captioned as “George” in one) and a small amount of premiere images from the London opening – around 30 images between the two sections in total. Text on “Rabbit Religion” appears to be based on lengthy extracts from the book, while the Glossary (seemingly for kids, since adults immediately get the alternative rabbit-slang for our everyday words) is presumably the same “rabbit words” from the US edition. Some cast and crew Biographies turn out to merely be credit listings for the selected few, though these do reveal that Hurt returned to the warren to voice Woundwort in the later TV series, and senior animator Phil Duncan came from a Disney background that included a slew of Pluto cartoons and features such as Fantasia and Bambi.

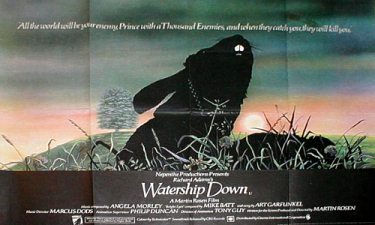

Finally, the sleeve reflects a unique idea: a representation of the film’s international DVD design on one side, and another, Big Sky-exclusive version on the other, which more closely resembles the gorgeous theatrical art from the film’s original release poster. In fact, Rosen makes a point of saying that he disliked the brighter, more child-friendly artwork used on the wider DVD release, which could have prompted Big Sky to include the more sombre artwork here. It certainly accurately reflects the atmosphere of the film much more evocatively than any other, and marks Watership Down out as the original and brave – not to mention touching in a non-saccharine, positive way – piece of filmmaking that it is.

NOTE: it should be pointed out that the UK also has a “deluxe edition” of the movie, available from Amazon.co.uk, which features different and possibly just as relevant extras, among them two featurettes including a conversation with director Rosen and editor Terry Rawlings, and a look at the film’s voices and animation, plus three storyboard scene comparisons, but not the exceptional director’s commentary found on this Australian disc.

THE PLAGUE DOGS: Exclusive UNCUT Extended Edition ORDER FROM EZY-DVD HERE

While Watership Down may be the more accessible feature between the two, The Plague Dogs, director Martin Rosen’s follow-up and again based on a Richard Adams novel, remains the deeper, more urgent film. Thus so, it was brutally cut on its American release after a poor showing internationally, and has ended up an amazingly hard film to see in its uncut form – until now!

Once again, Rosen uses animation as the tool to tell the story. As such, and if such a film could even be conceived as being made today, no doubt it would be told with CGI dogs living out their doomed lives, perhaps within live-action environments, but back in the early 1980s, when Rosen wanted to adapt the story to film, the only technology that would allow this was animation, and he again took the bold step of planning and overseeing the film as if he would a live-action feature. Rosen had started out as an independent producer in the 1960s, hitting it big with Ken Russell’s infamous Women In Love, with Alan Bates, Oliver Reed and Glenda Jackson, and making his directorial debut with Watership Down, the success of which led to him into this second collaboration with writer Adams. Like the later, similarly toned and equally brilliant Raymond Briggs adaptation When The Wind Blows, The Plague Dogs is a much, much darker film than Watership Down, having, at its heart, a powerful anti-animal testing story, which is deceptively simple.

Opening in an animal testing facility in England, we are never told explicitly what treatment the dogs, Rowf and Snitter, have been subjected to, but it is certainly enough for them to be desperate enough to want to escape. This they do, late one night, launching a countywide sweep by the humans to search and destroy. Lost and confused, the dogs amble through England’s north Lake District, searching for “freedom”, though scorned by every other animal they meet as being touched in some way that seems foreign to the rest of them. Through chance encounters with humans, whom we overhear, the audience learns that the dogs have been infected with an illness and were under examination. It seems Snitter, the smaller of the two, has undergone some further surgery, and is in need of urgent attention. Slowly, the dogs make their way towards the coast, where the humans, among them a heavy-duty British army unit, are closing in…

Unlike any other animated film yet released, even to this day, The Plague Dogs takes a tough subject and turns it into an extraordinary experience. And watching The Plague Dogs IS an experience. Perhaps it’s closest to Bambi in its stark portrayal of realism, but there are no funny bunnies here to take away the sting, nor even the occasional playfulness or excitement to be found in Rosen’s own Watership Down. The Plague Dogs is a bleak film, full of the realities of life, and that the protagonists are dogs draws on man’s affinity to them in making one feel even more for their plight. Likewise the muted colors, full of the melancholy mood of rural England, strike a harshness that doesn’t set out to make the countryside cosy and inviting.

The animation was handled by much of the same crew as that on Watership Down, clearly working on a higher level here with the experience they developed after one feature already under their belts. There are some future big names in the credits too, among them Brad Bird, who would of course go on to be involved in a number of much celebrated shows and films, including his wonderful The Iron Giant and a Best Animated Feature Oscar winner for The Incredibles – as about as far as one could go from The Plague Dogs if searching for polar opposites! The drawing here is amazingly lifelike and naturalistic – especially in the extraordinary, non-rotoscoped human animation – lending it not only another level of involvement, but another layer of frustration in that so few people – even in animation circles – have ever had the chance to see it in its original version until this release.

The voice work is spot on too, with John Hurt returning to perform for Rosen after Watership Down in the role of Snitter, and Christopher Benjamin as Rowf, a part which had originally been offered to Jeremy Irons, but who had not sounded quite right. The rest of the cast, among them James Bolam as The Tod, a wily fox the pair encounter, Nigel Hawthorne as one of the “whitecoat” doctors and, in smaller roles, Warren Mitchell and Patrick Stewart, are cold and calculating, providing the unnaturalness that Rowf and Snitter experience while out on their adventures, and coming over as intentionally unnerving.

The film sparks a frank discussion on animal testing and cruelty: “There must be some reason, mustn’t there?” Rowf asks rhetorically, “It must do some sort of good”. That we warm to Snitter and Rowf does put author Adams and the filmmakers down rather firmly on one side of the argument, and the faceless, humourless humans don’t put up much dispute on their side. The dogs’ break for freedom is born more from desperate frustration and wishing to bring to an end their current situation than any real malice or need for revenge on their captors, even though they realize from the outset that those captors will chase them and want bring them back. During the pursuit, the dogs likewise only carry out their confused actions with a natural desire to survive.

At one moment in the film, an event occurs that places them in a situation which offers no chance of redemption – an incident that only strives to point out their animal instinct as well as reaffirming that Rosen has taken a decidedly different approach with his two films than the Disney of today could ever imagine. Of course, ultimately the dogs’ journey is futile, being an escape to nowhere: they don’t know their location and have no idea where they are going to; at least in Watership Down, Fiver had a premonition of where the rabbits should be headed, here it’s just a memory from Snitter’s past that was lost long ago. It’s interesting when we first see Rowf that he is submerged deep in water, fighting for his life, as this is also how the film ends, almost as with a bookend, intentional or not, suggesting that even if the situation has remained the same, then at least the dogs have chosen to tackle it on their own terms.

After a 1982 release of the 103-minute film in the UK and internationally, Embassy Pictures balked at the fairly depressing picture and ordered cuts be made to soften the blow before they would agree to distribution in the US. A truncated cut, running just 85 minutes, was premiered in the December of 1983, before being given a limited release across the United States in 1984. For the most part, it’s this cut that has been widely available since then, even around the world. In a futile attempt to make the film more appealing to family audiences, the shortened cut was marketed more as an adventure movie featuring two lovable dogs on the run – something that no doubt surprised and distressed audiences who ended up witnessing the harrowing story unfold, cuts or no cuts!

In the end, and perhaps predictably, The Plague Dogs was deemed a failure, not least because the “happy ending” version was still a dark film and wasn’t able to either appeal to families nor those adults who might have made the more mature full-length version successfully recognised. As such, The Plague Dogs has gone down as a bit of a cult film (and one often cited by activists who were impressionable young people unwittingly “subjected” to the it in original theatrical or video release and had its message lodged powerfully in their minds). It is only now, thanks to Big Sky’s relationship with director Martin Rosen, who loaned them his own personal print of the film, that those other than persistent die-hard fans can finally see this uncut original on anything other than battered and bruised VHS bootlegs.

Presented in the 1.33:1 full-screen ratio of this original print, there seems to be no great framing problems, and logic would dictate that the film was shot to an open matte negative which would have been cropped top and bottom in theaters – certainly blowing it up to fill a 16×9 display had no adverse effects. This taller aspect does reveal more of the animated image, there are no instances of chopped off characters or tight framing on the sides, and being the fully uncut edition gains so much more than any possible slivers lost around the edges. The added scenes add not so much to the actual story (there were never any plot twists or subplots missing), but to the overall mood of the film. Already Rosen had taken a few liberties with the book (most notably, Snitter’s master remained alive and they were eventually reunited), and had made the dogs less “innocent” to begin with. The change in cut is immediately noticed with the addition of dates that number the days of action the story covers, missing in the US edit. We also get an exchange early on between Snitter and a Pekinese on how the dogs should open a door during their escape, but mostly the additions are scene extensions or moments of dialogue that point towards the dogs – especially Rowf’s attitude to resorting to violence for survival – not being as “cute” as the US distributors might have liked.

One sequence that IS vital to the film is where The Tod’s wiley nature gets the better of the dogs, ingratiating himself into their group and suggesting that they “turn wild” as a ulterior motive in basically having them put themselves in danger in catching sheep for him. There are a couple of additional “hunting” sequences here, where The Tod shows Rowf and Snitter the ways of wild fishing, chicken coup raiding, deer hunting and frog catching – the last of which is significant in that Rowf succeeds in making a kill. The other moments lost in the truncated cut mostly feature the reaction of the humans in the local vicinity, and though these are relatively plotless, shorter scenes, they do provide more meat on the bone, being a way to explain the average man’s uncertainty in the situation against the scientists’ nonchalant aspect (and public denial) of the job at hand. Finally, the extra sequences add depth to all the animals’ characters and situations, and broadens the imposing feeling of their confused misunderstanding as the net is formed and begins to close in around them.

When it comes to supplements, one may be a little disappointed to learn after the packed Watership disc that things are otherwise pretty sparse here. On speaking to Big Sky, it seems the choice here was to issue the fully uncut edition of the film from Rosen’s print instead of incurring the extra costs of recording an audio commentary (that said, I doubt if Rosen would have been happy remarking on the truncated version of his film anyway, and he does very briefly touch on the film’s production mood in the exemplary Watership Down discussion on that disc). What we do get, though, and making for interesting viewing, is exactly that entire edited version as a second cut (the 103 minute 1982 version runs 99 minutes here, thanks to PAL’s 4% speed and pitch change, while the 1983 shortened edition stretches to under just 82 minutes). Comparing the two, I have to raise my hands in wonderment at what Embassy were striving to do by deleting the material they did, creating a diluted film that is nonetheless still very much a disturbing story, whichever way one tries to cut it.

The US edited version expectedly looks as good, clean and stable as any previously issued version (no doubt taken from the same source), but when it comes to Rosen’s own print of the longer cut, things are in pretty terrible shape, with steady gate weave and more grain throughout, and a sad though expected amount of print artefacts around the reel changes. When the image settles down, it’s not so bad, and to be honest I found myself dragged out of the story only once or twice while the film unspooled due to age related defects. To be noted is the United Artists logo on the front of this cut, so there may be hope there in finding a cleaner element perhaps for future release. The last know issuer of the full version, on VHS in a sell-through edition for the UK market (luckily the tape edition I own), was the Warner Bros-distributed Weintraub library edition – surely somewhere in the world this exists, even as video dupe master!?

Offering two versions of the movie, Big Sky opted sensibly for a dual-layered disc, so at least the image doesn’t suffer from any extra digital anomalies, but it’s clear from the outset that the print is a viewing copy that has been often used. It also may be a tad dark in places, and while colors are good, if a little faded, there are some stretches where the red in the image is severely desaturated (see comparison frames). The Plague Dogs, like Watership Down, has a fairly pastel palette, if a little more bleak, and coming from an editor’s background, I would love to have seen Big Sky spend more time on judicious color correction or perhaps create a “combination” version where the previously excised footage had been cut back into the much cleaner release print. However, I’m guessing cost would have again been a consideration, and they have done their best to faithfully reproduce the image, but my own punching up and balancing of the colors fashioned more acceptable levels in approximating the look of the sharper, but edited, release print.

As with the same company’s Watership Down, The Plague Dogs comes to this disc in a decent Dolby 2.0 Stereo track, taken directly from the print. Though the film isn’t one that cries out for plenty of surround activity (it’s far too introspective and talky for any sonic bells and whistles), this mix follows the video’s lead in being perfectly acceptable. The desolate sounds of the wilderness, the far off echoes of civilization, and the monotone, cold and scientific approach of the “whitecoats” are all evocatively realized, while Rowf, Snitter and The Tod’s dialogue provides more emotional dynamics, coming through strong and clean. The music, when it plays, spreads things around a little, and the heavy military climax ups the sound levels for maximum impact. Animated films are all about making the voices sound as if they are coming from the characters on screen, and the original soundtrack features expertly placed and equalized vocals, which have been well transferred to disc and lose nothing of their haunting quality.

Other than that, the main menu plays a lengthy, almost full-length version of Alan Price’s “Time And Tide”, a gospel-flavored plea that I never felt suited the film as much or as seamlessly as “Bright Eyes” did in Watership Down. The song was originally intended to only close the original cut, coming in softly and slowly over the final credits, though it was added to the front of the US version (setting the film off on the wrong foot) and begins to creep in much earlier during Rowf and Snitter’s final swim to “freedom”. The impact again of the original cut can easily be seen in these closing scenes’ pacing, being much more sedate in the director’s version as opposed to trying to create a false sense of uplift in the distributor’s. The other change to note is the style of credits, being dissolved pages in the extended as opposed to a general credit scroll on the edited version. In the supplements, we also get some “Selected Works” (basically notable credits for the main players, but which misspell the author’s name as “Addams” and includes what he felt about Watership Down rather than Plague Dogs), but no useful and perhaps much needed background text on the movie.

The sleeve is double sided as with Big Sky’s Watership cover, this time with the original art front and center on the outer side and a chapter index printed on the flipside. In the UK, an early Anchor Bay edition supposedly added a trailer (and a quick reminder here that even UK issues only contain the truncated cut), though this was actually little more than a couple of minutes of “Time And Tide” accompanied by several scenes from the film. This Region Four edition comes with that same theatrical trailer song clip which, for me, highlights the fact that Price’s track really doesn’t suit the mood of the picture, especially over the random images selected here that run through the film’s basic story, inevitably playing up the adventure/drama and leaning away from the desperate nature of the characters’ circumstances.

Essentially, The Plague Dogs is a feature-length wait for the two leads to meet their doom, and even with the ambiguous ending (which keeps hope alive), its themes are certainly not typical Disney-style fare for the family audience and still then hard to swallow by adults. But The Plague Dogs deserves more than its standing in some quarters will have you believe. It’s a deep and often disturbing film that marks its own patch in the animation landscape, being not an adult sci-fi extravaganza or a titillating sex-and-drugs social comedy, but a heartfelt, serious and affecting drama which does offer something very rare: a truly rewarding animated experience for grown-ups.

Big Sky’s presentation goes some way to righting the wrongs of the past, though that such “independent” films such as Wizards, Fire And Ice and Rock And Rule can get such feature packed, restored or 2-disc extravaganzas over much more accomplished fare like this is a crying shame. However, it’s a giant two thumbs up towards Big Sky and their efforts at making both Watership Down and The Plague Dogs available in legitimate DVD versions, especially in allowing Rosen the chance to comment on Watership and the fully uncut “extended” edition of Plague Dogs to be seen at last – something that fans have been waiting for patiently.

Unsurprisingly, possibly given the turmoil over the release of the film, Martin Rosen would only go on to direct one more (live-action) film, in 1987, and eventually returned to his greatest achievement by re-imagining Watership Down as the relatively successful, but overly simplified, television series of the late 1990s. With these very special editions on DVD, let’s hope that renewed interest in his work stirs up a passion to supervise at least one more project, or perhaps even a new animated feature. Certainly his two films considered here remain vital contributions to animated history, and important films that prompt us to remember that animation can offer so much more than either dancing mice or babe-featured laser battles.

Top marks all around, and both highly recommended mature animation viewing!