On January 21 2020, Terry Jones, best known as a member of the legendary and influential comedy troupe Monty Python, passed away at the age of 77. Playing such memorable characters as the naked organist, the waitress selling Spam dishes, Ron Obvious, and Mr. Creosote, he would also be the primary director of the group’s films. But while he had garnered lasting recognition as part of Monty Python, his career outside of it was relatively low-key in comparison to most of the other members.

His notable credits include writing the screenplay to the Jim Henson feature Labyrinth, although it has since become known that the final film contained little of what he originally wrote. He also wrote, directed, and starred in a live-action adaption of The Wind in the Willows but, while the film was well received, it suffered from a lack of distribution support and was not widely seen. There was also one interesting tidbit that many probably aren’t aware of: did you know he created an animated series called Blazing Dragons?

Blazing Dragons was produced by the Canadian-based Nelvana studio and the French-based Ellipse Animation. Jones created the premise to be a spoof of the King Arthur legend, spinning it to where anthropomorphic dragons were the protagonists and humans the antagonists. The show ran for two seasons from September 9, 1996 to February 16, 1998 on Teletoon in Canada and also on the former Carlton Television (now ITV London) in the United Kingdom, having a brief run in the United States on Toon Disney in the early 2000s.

Now, it should be noted that Jones admitted he had little involvement with the show. In a 2004 interview with IGN, Jones remarked, “Oh bugger me! Oh dear… I’ve never really watched that. Blazing Dragons was… I came up with the idea during a drunken lunch, I think…” He would further elaborate, “I was never able to develop the idea because I was too involved doing something else.” He was presumably busy making The Wind in the Willows, which was released around the same time as when Blazing Dragons premiered.

“He was very friendly,” series director Lawrence Jacobs said about Jones from when they spoke briefly over the series’ development. “He had a different idea for design style that would have been a problem for production (money and time) and he graciously backed off and wished us all good luck and that was it! All cherry oh and have some fun!”

The actual developing of the show was undertaken by Gavin Scott, who was a friend of Jones’ after working on The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles episode Barcelona, May 1917 that Scott wrote and Jones directed. According to scriptwriter and second season story editor Erika Strobel, “Gavin had written a series bible (concept, characters etc.) as well as a pilot script.” So Jones and Scott would be credited as the creators while Jones would also be an executive producer since Nelvana needed his approval to produce the series.

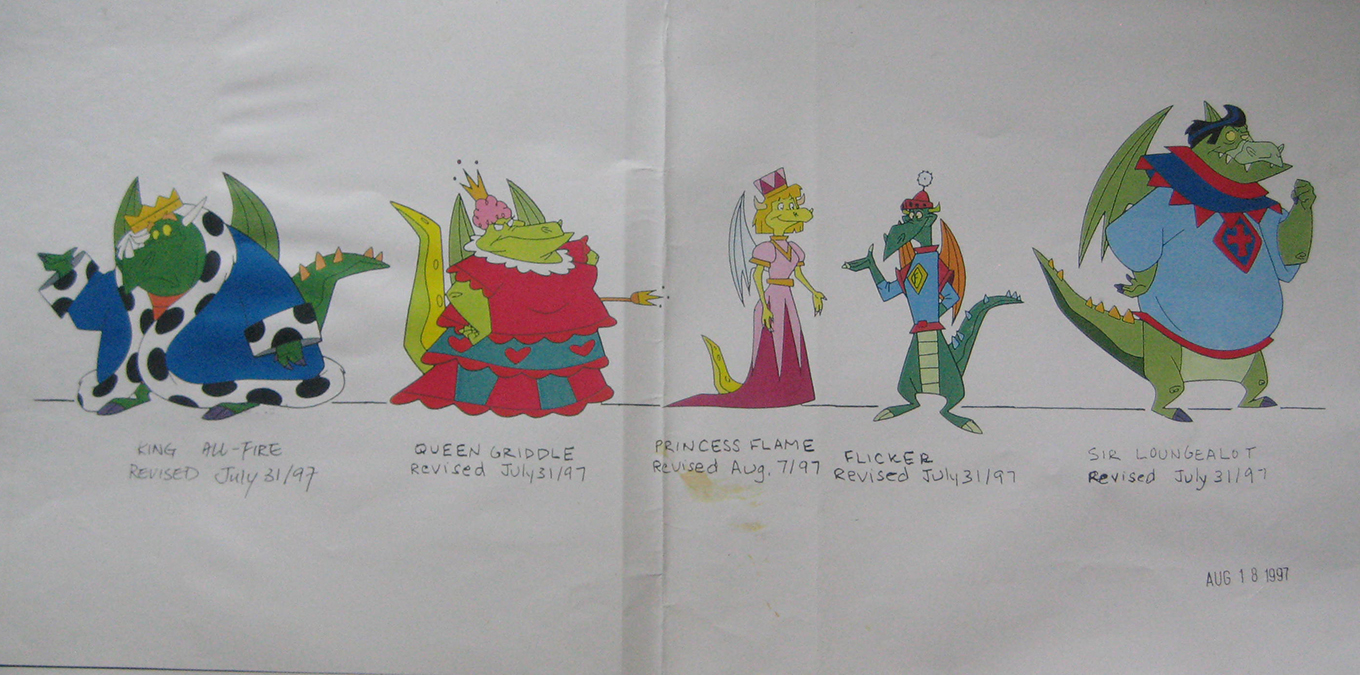

In Blazing Dragons, King Allfire and his Knights of the Square Table defended their kingdom of Camelhot against the tyranny of Count Geoffrey and his minions. At the center of the story was Flicker, a young inventor who aspired to be a knight. To that end, he had become squire to the head knight Sir Loungelot. Only Loungelot proved to be egotistical and a lazy oaf who treated Flicker more of a servant than a squire. What’s more, he would take credit for Flicker’s success, often by being at the right place at the right time.

The idea of working on a show that had been conceived by a member of Monty Python was enticing. “I had just finished directing another series at Nelvana and this series came up that was created by Terry Jones,” recalled Jacobs. “I was asked if I was interested and I guess I thought about it for two seconds!”

For Strobel, being shown the initial concept art by Jacobs was enough to win her over from the beginning. “I fell in love with it instantly and told him (begged him) to be a part of it,” she said. “Then about 6 months later we found out the origins and you can imagine how freaked out I was that Terry Jones (my hero!) had come up with this idea.”

The writers weren’t fond of Scott’s original pilot script, however. Strobel would elaborate that “none of us thought it was funny.” So after seeking Jones’ blessing, Scott was let go and Nelvana set about the writers to develop a better pilot script to produce. Strobel noted that this “was a massive undertaking with several board room meetings and rewrites – every writer adding to it to make it better.”

For the first season, most of the thirteen thirty-minute episodes followed a roughly similar story structure. Camelhot would be occupied with an activity, Geoffrey would attempt a takeover by taking advantage of the situation, then Flicker would save the day, usually by a featured invention. Knowing that the show was created by Terry Jones, the writers would seemingly be inspired to incorporate Pythonesque (an actual Oxford English Dictionary word) humor to make their stories unique.

In an example, the episode Tournament Day saw Queen Griddle set up a tournament with the winner marrying Princess Flame to the latter’s chagrin. Geoffrey would send his minions, disguised as one knight, to cheat with attached mechanisms. Flicker would save the situation utilizing the magic net (or magnet) in revealing the humans to be attacked by an angry mob. The magic net’s main power source was a giant potato that resembled Sir Loungelot but, instead of being insulted, he would admire it, bringing it with him for drinks and even for a bath.

The premise would help in making the visual style and animation stand out from other shows at the time. “I believe I had done some scribbles on paper,” Jacobs said of designing the series, “and handed it to Chuck Gammage to develop further and then Doug Thoms did more character and location development.” The characters were designed so that their personalities would be highlighted, allowing them to stand out from one another. One could tell that Sir Burnevere looked like the elderly, overly educated knight that he was.

Though the show was unique both in premise and in presentation, it did have trouble garnering viewership during the first season, particularly in North America. “I don’t think it got a sale in the US at first and that was the big market to break,” Jacobs explained. “Disney and Warner Brothers owned a lot of the broadcast options back then, when there were only five channels! I believe it did well in the UK, as it did come back for a second season.”

But while Blazing Dragons did receive a second season, it went through some major changes in the interim. “When the possibility of a second season came up I was asked what I’d do to make the show better and I suggested we got to the shorter format,” said Jacobs. This meant the episode length was trimmed down from a thirty-minute format to a fifteen-minute format.

“I also think that some people on the creative team felt the shows were too long and dragged out in the half-hour format,” Strobel noted. While she was promoted to story editor for the second season, she would have preferred continuing with the original format. “You can explore ‘character’ more in a half-hour – whereas eleven minutes forces you to just write back-to-back gags and plot. I’ve always preferred character stories to action stories. The second season was exhausting to write – for this reason.”

The change in format would cause the story structure for each episode to be revised. Most were about just the knights themselves engaged in an activity and then having to get out of a troubling situation they would usually cause themselves. It was perhaps because of this that the number of characters diminished. Some characters, like Princess Flame and even Count Geoffrey, were used less and less as the second season progressed. Other characters, like Sir Galahot and Sir Hotbreath, disappeared completely.

The writing wasn’t the only aspect of the show that underwent changes. “The producers were the ones that made decisions to simplify the character designs to make animation production a bit easier,” Jacobs explained. Among the art changes made included a radical redesign of Count Geoffrey, which was showcased in the first second season episode aptly titled A Killer Makeover. This was an attempt to make him appear more sinister and villainous.

Furthermore, there were additional issues that affected the overall presentation of the second season. “The series line producer for the second season made the mistake of assuming the length of a half episode was much longer than the Channel 4 (UK) specs,” said Jacobs. “We had to scramble and tighten a lot of the episodes to fit into a shorter time slot at the last moment! This created some frenetic pacing in places but that wasn’t really a bad idea in the end!”

However, it wasn’t enough to keep the show going after the second season. With low viewership in North America and the crew having to work themselves into exhaustion to meet the changes between seasons, Blazing Dragons was canceled after the last episode aired.

Even after it had ended, the show seemed to face continued censorship, at least in North America. “Since it was primarily a show for the UK and Europe we didn’t have as much meddling in creative by non-creatives with early childhood training degrees as we did with projects for North America,” said Jacobs. There apparently was a lot of objection to the content presented in Canada. And when Blazing Dragons did air in the United States, episodes were heavily edited to remove subject matters deemed taboo at the time.

One subject that was the most taboo was Sir Blaze and his implied homosexuality. Strobel noted that the writers were mindful of having such a character in a children’s show and were careful with how he was written. “Blaze was written as ‘flamboyant’ and ‘campy’,” she explained. “It was just understood he was ‘gay’ without really saying it. But we wrote it more from the point of view that he had style, he was sensitive, etc. We never ever referenced his gayness with over sexuality towards another character.”

Perhaps the biggest obstacle for the animated series was lack of recognition. One would think that advertising the involvement of a member of Monty Python would have been beneficial in promoting the series. “I recall that there wasn’t a lot and I’m not sure why,” Jacobs noted. “Possibly that Monty Python was perceived as adult entertainment and not mainstream American.”

Another possible contributing factor might have been an accompanying video game. “I do recall that at one point there were some discussions,” Jacobs noted. “But way back then video games were not the huge thing they are today and we were in the middle of production and didn’t have time to become involved.” Strobel added that she hadn’t heard about the video game until after the fact.

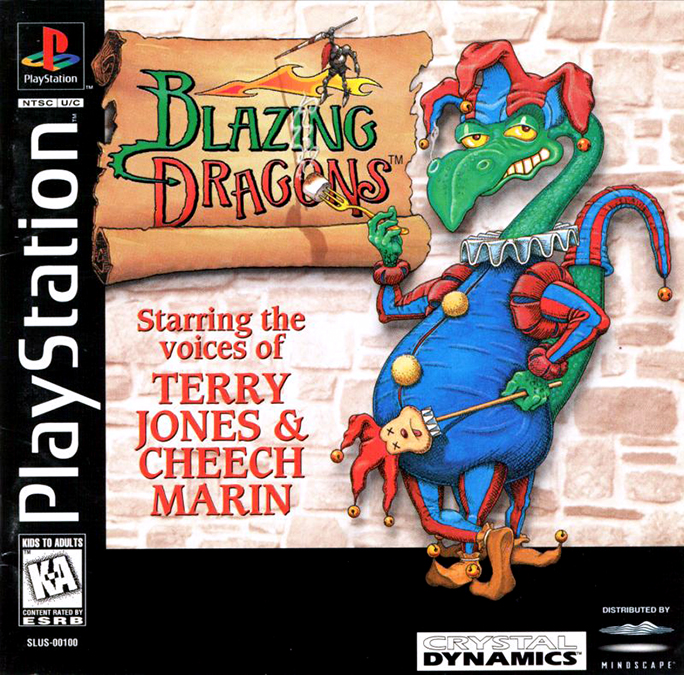

The Blazing Dragons video game was developed by Illusions Gaming Company and published by Crystal Dynamics for the Sony Playstation and Sega Saturn. It was scheduled to be released in late 1995 as Dragons of the Square Table, according to a preview listing in GamePro magazine, but was pushed to October 31, 1996 in North America and days later in the United Kingdom to presumably coincide with the show airing.

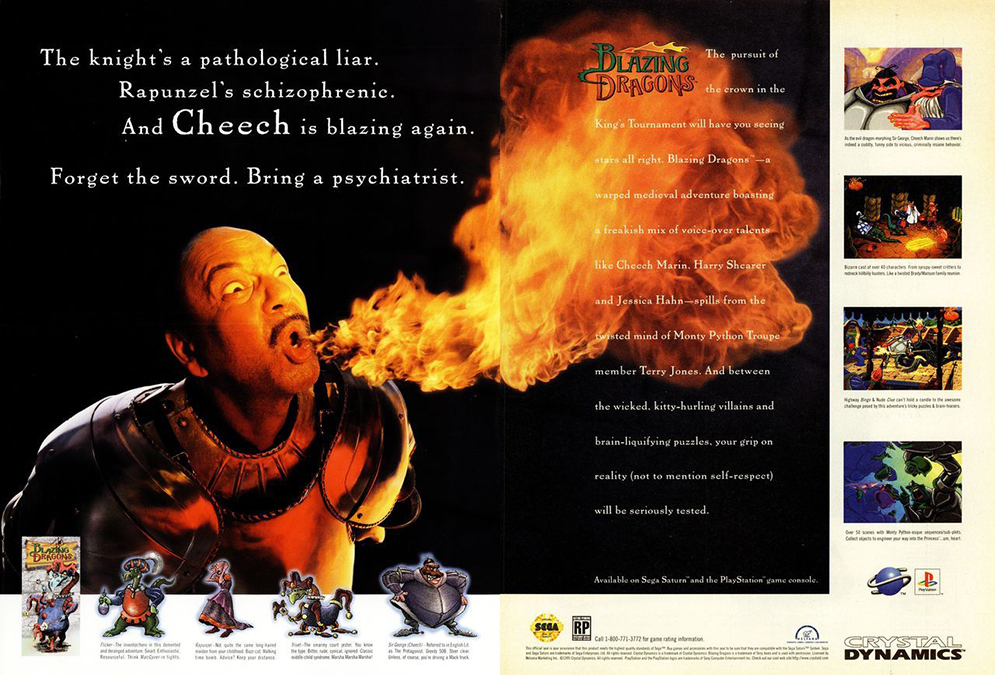

The video game retained Jones’ credit as creator along with some of the characters and the premise of spoofing the King Arthur legend with dragons as the protagonists and humans as the antagonists. But there wasn’t much else that tied it with the animated series. In fact, it presented a completely different story from the show, utilizing a different visual style, and the characters who crossed over had their personalities altered. What’s more, the game’s advertising made no mention of the show existing save for a small inclusion of the Nelvana logo.

Ironically, Jones seems to have had a little more involvement with the Blazing Dragons video game: he was given sole credit as creator, while Scott was given special thanks, and would voice a few characters in the game, including Sir Burnevere and disgruntled court jester Trivet. Furthermore, Crystal Dynamics promoted his involvement as creator and voice talent on the game’s cover art as well as in advertising.

Speaking of voice talent, there was quite a difference in the cast. The animated series featured known Canadian talent such as Edward Glen, Aron Tager, Steven Sutcliffe, and Stephanie Morgenstern. The video game featured known American talent such as Jim Cummings, Rob Paulsen, Jess Harnell, and Kath Soucie. The video game also featured well-known actor Cheech Marin voicing characters, in particular the gluttonous main villain Sir George, and, like Jones, his involvement was promoted in the advertising.

But while the video game ended up garnering more recognition than the animated series, it really wasn’t by much. The game was a point-and-click graphic adventure akin to LucasArts titles like the Monkey Island series and Maniac Mansion. However, the genre, which was largely supported by a niche audience, was experiencing a downturn by 1996 and was very rarely explored on consoles at the time, being more prevalent on personal computers. As such, the game had just as much trouble gaining an audience.

With little recognition outside of those who had actually seen the series or played the video game, Blazing Dragons would seemingly fade into obscurity within a few years. There was hardly any merchandise associated with the series save for some DVDs of the show released in France and Germany along with at least one known VHS cassette tape in Canada. What’s more, doing anything further with the Blazing Dragons property would require the approval of Jones, who seemed reluctant to renew interest in the series.

Sadly, Jones’ works tended to lack the distribution support needed to be seen more widely. Even his last directorial effort, the 2015 science-fiction comedy Absolutely Anything, suffered the same fate, and this was despite an ensemble cast that included Simon Pegg, Kate Beckinsale, the then-remaining members of Monty Python, and Robin Williams in what would be his last performance. It also happened to be co-written by Gavin Scott, sharing another similarity to Blazing Dragons, and being treated no differently.

And yet Blazing Dragons refuses to totally disappear. Thanks to aspiring animator Natacha Statari, a fan-base has emerged over the past several years to raise awareness in the series. Fan-made content can be seen rather steadily online, drawing the interest of curious viewers and leading them to discover both the show and the video game. With support from members of the cast and crew, in particular Jacobs and Strobel, Statari’s efforts would appear to be paying off, with the show becoming more accessible to watch via availability on YouTube, on Amazon Video for purchase, and as of writing, streamed for free on Tubi.

Though he ultimately had little to do with the show, that Monty Python’s Terry Jones created an animated series was fascinating unto itself. Blazing Dragons offered something unique in spoofing medieval folklore in a way that played against type with dragons as heroes and humans as villains. Complications during the making of the series prevented it from being widely seen, yet it entertained those who did watch and remember it fondly. Perhaps Jones would be pleased to know this creation of his had its fans, and that they continue to blaze to this day.

With special thanks to Lawrence Jacobs for his comments and use of concept art and to Natacha Statari, whose Blazing Dragons Revolution proved an invaluable resource including her interview with the late Erika Strobel.

I've actually been thinking a lot about Blazing Dragons for twenty years since first playing the video game way back when. Always been a big fan of the point-and-click graphic adventure genre and was delighted to see one on Playstation at the time, especially with the involvement of Terry Jones and Cheech Marin.

I happened to be living in Pennsylvania during the animated series' brief run on Toon Disney, which I managed to get. Thing was, on top of the apparent censorship that I didn't know about until later, it aired at like 4am or some extreme hour at night/morning. So one really wanted to watch it in order to do so, which I willed myself to do on a number of occasions. It was around early 2002, I think, when the show got pulled.

Interested in seeing if we can get some further discussions about the series going here.