Production I.G (2015), Universal Studios Home Video/GKids (March 7, 2017), 1 Blu-ray + 1 DVD, 90 mins, 1.78:1 ratio, DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1, Rated PG-13, Retail: $29.98

Storyboard:

A series of occurrences depict the life of an artist and his talented daughter in Edo era Japan.

The Sweatbox Review:

The subject of this review, as with so many other Japanese animated films, began life as a Japanese comic book, or manga. This particular manga was a biographical story of a family that included O-Ei, and her father, the great artist Hokusai, originally known as Tetsuzo. They lived in the Edo period of Japan (1603-1868), a stable era when the country had a feudal system in place, led by the shogun nationally and the more local daimyos. Culturally, the arts were in favour, which meant fame for the artists who were most greatly appreciated. Hokusai was among the greatest artists of the time period, known mostly for his woodcuts but also his paintings.

The film begins in 1814, with Tetsuzo in his mid-fifties, and portrayed as primarily a painter. He works in a studio with his daughter, O-Ei. Tetsuzo is portrayed here as a less than sympathetic figure, a quiet and undemonstrative person who cares far more about his work than his relationships. O-Ei toils away for him, providing artwork for the commissions that they have accepted, while also giving instruction, encouragement, or (mostly) criticism to fellow artists who come by to visit. O-Ei does not really like her father, but she must respect his talent and his place in society. And while she may resent his less noble qualities, she tries hard to match his ability as an artist. Of course, they are a lot alike, except in how they care of family. Tetsuzo is distant, while O-Ei spends time regularly with her mother and with her blind, sick little sister. Tetsuzo fears illness and death, so he stays away from his youngest offspring altogether.

The relationship between O-Ei and her sister forms the greatest thread of story in the film. They have the tale’s strongest and most touching relationship, sharing times out walking or riding in boats, with O-Ei valiantly trying to make excuses for their father. Intermixed with those scenes, we see several visits from fellow artists, a trip to a brothel, a fire, O-Ei’s struggle to depict erotic images, and a few instances of mysticism that relate to Japanese mythology and Buddhism. These latter scenes may make less sense to those who have little knowledge of such things, but it makes for a great excuse to research another culture.

Miss Hokusai eschews western notions of storytelling, focusing less on plot or character development (though there is characterization aplenty), and instead showing a sequence of events in the life of these characters. The manga, apparently, followed the same format. Episodic storytelling is a form that works well in comics, but we in the West are less used to it in feature films. This may lead to a sense of unfulfillment in watching Miss Hokusai, unless one sets one’s expectations accordingly. Not much really happens in the film in terms of moving the characters forward, as it is more about life’s moments than about any grand theme. Things happen, then more things happen. And life goes on. Or sometimes it doesn’t.

There is a theme, though, that is spelled out almost too clearly at the end of the film. The point is made that we may not all lead rich or rewarding lives, so we must focus on enjoying the small happenings and everyday moments. It’s not a bad theme, though it’s also not particularly inspiring for those that live in Western culture, which focuses so much on achievement and glory. The notion of “everyday suchness” springs from Buddhist philosophy, which remains extremely foreign in concept to Western society. Of course, that does not mean that we cannot learn from it.

In my first viewing of this film, I was left distinctly unimpressed. The animation is beautiful, the imagery lovingly rendered, and it is fascinating to view an earlier version of Tokyo during the Edo period. However, my teenage daughter and I both wondered what the point of the film was. Why make a film that has occurrences but so little development? Why didn’t more happen? What did it all mean?

But those are the wrong questions for a film like this. This is a film meant to simply be experienced. Whether or not you “feel” anything because of it will depend on your nature, and your mood. Some have called it a masterpiece, and indeed it won the Jury Award at Annency and several awards at the Fantasia International Film Festival. I’m not ready yet to give it quite so high praise, but I’m interested in getting there. I need to revisit it, with an open mind, and learn to appreciate “everyday suchness” in my own life.

Is This Thing Loaded?

The Making Of Miss Hokusai documentary (1:56:06) runs far longer than the film itself, so you now it’s pretty complete. It examines the project’s origins, and the enthusiasm of its director Keiichi Hara in bringing to life the admired work of revered manga creator Hinako Sugiura. Unfortunately, the pressure of the project, primarily sprouting out of Hara’s reverence for the source material and its late creator, proves too much. Hara has a breakdown and leaves the project for six months! It’s a gripping story, as we follow the team try to soldier on without him, guided by the producer and the supervising animator who becomes de facto director. Even at two hours, presented naturally in Japanese with English subtitles, I was riveted.

Miss Hokusai’s Theatrical Trailer (2:12) is available on the disc as well.

The Blu-ray starts up with home video ads for Only Yesterday, A Monster Calls, When Marnie Was There, and Sing. From the menu system, you may also select Trailers for April And The Extraordinary World, Only Yesterday, Phantom Boy, and When Marnie Was There.

The DVD has all the trailers, but only a 15-minute excerpt from the Making Of documentary, so the full-length version is exclusive to the Blu-ray.

Case Study:

Universal packages this in its standard GKids presentation: regular Blu-ray case with a non-embossed slip, with the GKids logo at the top of the spine to match other GKids titles on your shelf. The set has DVD and Blu-ray on opposing sides of the inner case. There is also a Digital HD code included on an insert.

Ink And Paint:

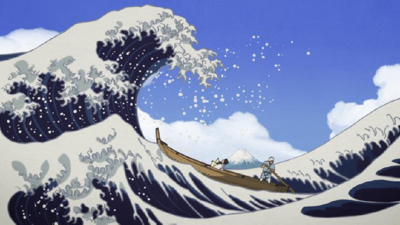

I can find no fault with this video presentation. The imagery in the film is strong artistically, sometimes evoking some of Hokusai’s famous works in addition to presenting slices of everyday life. It is all presented perfectly on the Blu-ray. The image is stable and I detected no issues with the transfer. The film looks beautiful.

Scratch Tracks:

The film’s soundtrack has a lovely natural mix, inviting us gently into a very real world— until visions of mythical creatures begin to parade, or a fire breaks out and destroys buildings; then, things get appropriately interesting. You can’t go wrong with either the Japanese or English track, each presented in lossless quality via DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1. There are English subtitles available, either for the hearing impaired and based on the English dub, or subs for the Japanese version.

The DVD has English and Japanese tracks in Dolby Digital 5.1, and the same subtitle options.

Final Cut:

I think this is a film that I will warm up to in time. My initial chilly response to it comes from cultural bias, and my appreciation for the film grew as I did some research and watched the documentary of how and why it was made. (The documentary itself validates a Blu-ray purchase.) Filmmaking is a broad medium, and that is no truer than in animation. With Miss Hokusai, the viewer is invited to enjoy what life has to offer on a daily basis. After all, life is not always about big jokes or daring adventures. It is mostly time spent working, or visiting with friends and family, or maybe pursuing quiet hobbies. The simple charms of the film come from the things we normally take for granted. If you can keep an open mind and allow yourself to enter into the world of the film, you may find yourself moved.

|  |