Walt Disney Feature Animation (June 21 1996), Walt Disney Home Entertainment (March 12 2013), Blu-ray plus two DVD discs, 91 and 66 mins plus supplements, 1080p high-definition 1.78:1 and 1.66:1 widescreen, DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1, Rated G, Retail: $39.99

Storyboard:

A disfigured man, Quasimodo, hidden away at the top of Notre Dame Cathedral’s tower as a bell ringer under the psychological control of his custodian, the power crazed Judge Frollo, dreams of a better, freer life for himself. When he falls for beautiful gypsy Esmeralda, Frollo’s jealousy and own desire for the girl proves too much for him to bear and a wedge between the two men splits their destinies in separate directions. Further creating tension is Paris’ new Captain of the Guard, Phoebus, in whom Esmeralda has taken an interest. With the quartet’s fate sealed, hopes and personalities are set to clash, in an animated retelling of Victor Hugo’s dramatic classic novel.

The Sweatbox Review:

Arriving in the summer of 1996, I have often wondered if Disney’s take on Victor Hugo’s archetypal French-Gothic novel The Hunchback Of Notre Dame had been released towards year’s end if the film might have enjoyed healthier commercial prospects and additional critical response. Up until Pocahontas the year before, Disney’s modern-era animated pictures had always been released around the end of year holiday period, around late October or early November, taking advantage of Thanksgiving weekend audiences hungry for family experiences, usually playing on through Christmas, and gaining critical momentum along the way so as to be noticed, at least in the song and score categories, in the following year’s Oscar nominations.

Winter releases were always Walt’s dates of choice, the majority of his original animated features being released right at the end or beginning of a new year, with reissues usually picking up the slack throughout the rest of the year. With the presumed wisdom being that families would rather vacation or visit the beach in the summer months, it wasn’t until the mid-1970s and the phenomenal success of Jaws and Star Wars that movie habits changed, with Disney itself switching titles between their traditional winter slot and the occasional summer release. However, when Steven Spielberg and Don Bluth’s An American Tail opened six months after Disney’s The Great Mouse Detective’s summer release in 1986 and made twice as much at the box-office, a swift change came into effect.

With the arrival of Michael Eisner, Frank Wells and Jeffrey Katzenberg as Disney’s new chiefs in 1984, an ambitious slate of one animated picture per year was soon announced and, without anything much in the way of competition, the traditional Thanksgiving date was pretty much “booked” annually for a slew of increasingly commercial and critically successful features. Oliver & Company in 1988 continued the revival of the Disney brand after Mouse Detective had reminded audiences – and the Studio – just what made Disney so great after the lean years of the previous decade, with the best yet to come. 1989 brought The Little Mermaid, arguably the film that set the template for the next twenty years and beyond.

Mermaid’s triumph was followed in 1990 by the slight blip of The Rescuers Down Under, a sequel to the Studio’s previous biggest grosser and a vastly overlooked movie in its own right that had possibly had its thunder stolen by the earlier issue of DuckTales: The Movie the same year, but if any film benefited from the critical praise being thrown Disney’s way then Beauty And The Beast was it. The first animated feature nominated for a Best Picture Oscar, Beauty also marked a change of pace in filmmaking at the Disney Studio, with Katzenberg especially intent on building on the film’s phenomenal success by creating another movie that could actually win the award. The thinking was that Beauty’s intelligence was the reason it created a deeper resonance with audiences and so the template for the next decade’s worth of films became dramatic-heavy stories that proved animation should be taken “seriously”.

The outright comedy of 1992’s Aladdin, from the Mermaid team, came too soon after Beauty to benefit from being taken too seriously – and was all the better for it – although the film did manage to pack in scenes of deeper emotion alongside its “classic Hollywood costume romp” feel, having been made more comedic after starting out as quite a sombre piece. Disney was on a winning streak, pushing other boundaries in terms of technique too: The Nightmare Before Christmas came the following year and reintroduced the notion of full-length stop-motion features, becoming a sizable cult hit into the bargain and inspiring a still-ongoing line of similar films. Ironically enough, one of the animation unit’s lesser anticipated films, The Lion King (1994) had been planned to have been “dumped” in the no-hope summer months and turned out to be a huge hit.

Thus, although Disney releases suddenly became big summer event movies, this coincided with Katzenberg’s desire to go with more mature story themes: I think what maybe hurt Pocahontas’ box-office ambitions in 1995 was a combination of non-too-kid-friendly plot and summer release date. Crucially, in trying to be more of a family film than the outright adult musical drama it should have been, the film didn’t play well to adults either, and what should have been a major critical hit has picked up the unfair reputation of being a bit of a dud even when the film was always destined to have been a solemn drama whether it was made in live-action or animation. I think the same scenario essentially applies to the Studio’s following film, The Hunchback Of Notre Dame.

Pocahontas had stealthily broached the sticky concept of the two male and female leads in a Disney animated film not ending up together – an ending forged by history as by anything else – and this could have been another element of why audiences, who like their feel-good endings, didn’t warm to the film as much as they did to those previously. Hunchback has the same issue, again since it follows an already established story path, but handles it much better as although we know Quasimodo – here shortened to a 1990s friendly Quasi – and Esmeralda can not become united, not least because her heart rests with Phoebus. But in a major sense, there is the happy ending we require: the two romantic leads (Phoebus being not much more than a supporting player for most of the film) do end up together, while Quasi finds his own acceptance too.

It’s a nicer, more Disney-fied ending than Hugo envisioned or even that the 1939 Charles Laughton film gave its hunchbacked hero, but it doesn’t insult the original novel either. I’m a huge fan of Laughton’s film – oh where or where is a restored Blu-ray!? – a black and white classic from the Golden Age of Hollywood and hailing from that banner year of 1939 that also saw the release of Gone With The Wind and The Wizard Of Oz (itself a product of the success of Walt’s Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs). Produced by a buoyant RKO Radio Pictures still flush with the success of King Kong from almost ten years earlier as well as almost a decade’s worth of singing and dancing hits featuring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, Hunchback benefited from luxurious production value and a terrific performance from Laughton that would be just one of a number of career highlights but that would define Quasimodo’s onscreen depiction forever more.

I haven’t read the Hugo novel for a long, long while (it’s a book that takes real dedication to plough through its rich details!), and so the RKO film probably informs my memory of the plot more than anything, but I do remember, on seeing that film once again after getting through the original book, that it did seem pretty faithful to Hugo generally, in that a 1939 product of the Hollywood system could be at that time. Disney’s film – apart from the fact that it becomes the second outing to turn a Hugo text into a musical after Les Misérables – naturally lightens things up a little, so that this film’s heavy, Frollo (voiced dominantly Tony Jay), doesn’t come too close to offending the Church, becoming, instead of a holy man, a feared judge, albeit one who holds his religion as close and highly as his dispensation of justice and law.

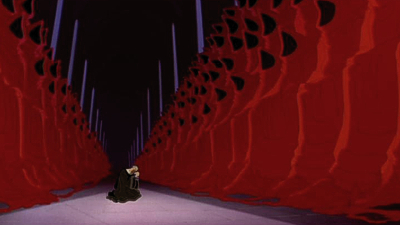

However, this doesn’t dampen Hugo’s intention and even the songs do little to soften some of the most mature themes to ever grace a Disney animated film, and in some cases actually heighten these moods – not for nothing that the theatrical G rating was considered too low considering some of the imagery on show. Of course, this is not to suggest that Disney’s Hunchback is full of sex and violence…but it isn’t completely devoid of them either. A tremendously sexual character, the gypsy Esmeralda’s physical and emotive charms are depicted clearly enough for her effect on the principle male characters of the story – Quasi, Frollo and Phoebus – to feel natural and inevitable. Quasimodo, after years of being kept prisoner by Frollo in his own bell tower, sees a caring mother figure, while Frollo’s mental state and vow of chastity is threatened by the unleashing of his repressed lust and the confusing thoughts and feelings this represents to him.

It’s interesting that both Quasi and Frollo get their big song sequence moments while Phoebus – who probably sees both aspects and more in Esmeralda, voiced huskily by Demi Moore – is more of a sketchy lead out of our four main characters. As voiced by Kevin Kline, he doesn’t quite ever fall into step with the other three, although he does get the girl by the end, so I guess that’s his consolation prize. Esmeralda couldn’t ever really go with Quasimodo, and certainly not with Frollo for all his want, so I guess being the conveniently placed hero does have its merits! As Quasimodo, Amadeus and Parenthood actor Tom Hulce was something of a surprise choice for a Disney lead, but he makes this vulnerable and sympathetic version of the character his own, providing the right amount of pathos and, unexpectedly, a very young vocal sound to the bell-ringer that suggests more character and personality than could ever be included in the script or backstory alone.

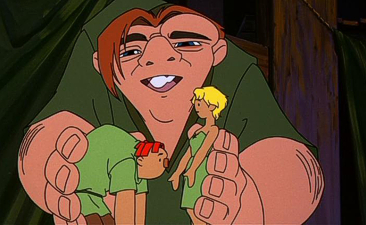

This being a Disney-fied edition of what is generally a pretty dark story, Quasi is naturally given some sidekicks to share the screen and lighten the mood with when things might just get a little too uneven for the kids. Now one could easily roll the eyes at this decision and make flippant comments, but the idea is actually Hugo’s – in the book, the lonely Quasimodo would sit and talk to the faces on the gargoyles that adorned the Notre Dame architecture, enjoying lengthy “conversations” with them in which he expressed his innermost thoughts and feelings, and hearing back their imagined replies. The ploy is put into great effect here, with three central figures turning from stone to life only whenever Quasi is alone, and so preserving the notion that this correspondence could be in Quasimodo’s mind only.

I do, however, have just one or two gripes about the gargoyles… As comedic characters they do somewhat feel a little shoehorned in, but stone gargoyles being about as far removed as one could think for Disney’s usual fluffy figure merchandising to take advantage of, kudos must be awarded to the filmmakers – the Oscar nominated Beauty And The Beast team of producer Don Hahn and directors Kirk Wise and Gary Trousdale, taking that film’s strengths to the next level here – for sticking to their guns and not finding a place for some cute ‘n’ cuddly birds, for instance. So the tone of the gargoyles may be a little off-kilter, at least in some scenes, but it isn’t always. No, my main gripe is in their names and more specifically just the female’s one…

The story’s author’s full name was Victor-Marie Hugo, back when Marie was essentially a gender neutral name. Since then, it has become more associated with its feminine connection, so why not – as in the case here where the two male gargoyles are called Victor and Hugo – is the female called Marie? There couldn’t be a more perfect representation and nod back to the book’s creator than in naming Quasimodo’s three gargoyle pals Victor, Marie and Hugo, but something obviously became lost in translation because here the character (voiced by screen veteran and long-time Disney associate Mary Wickes) has been christened Laverne. Okay, I get that it kinda, sorta sounds French, but there’s no other connection and I don’t get why the perfectly suited Victor, Hugo and Marie could have been used. I mean, come on, guys: the man had the exact right names you needed!

It’s a small gripe, to be sure, and one that is overshadowed in terms of the gargoyles’ appearances here by their own song moment, A Guy Like You. For The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, Disney composer of the day Alan Menken, nearing the end of the near-decade long roll that began with The Little Mermaid, really raises his game, as he had done musically with the same co-composer Stephen Schwartz for Pocahontas. With the death of his long-time writing partner, the incredible Howard Ashman, it is no small surprise that Menken has found it no mean feat to find a new collaborator that could match Ashman’s wordplay and storytelling through song skills, working with a number of lyricists and often swapping depending on the intended project and tone.

Schwartz, a song and score composer himself who had enjoyed stage success with Pippin (just re-opened on Broadway) and would also write the songs for DreamWorks’ The Prince Of Egypt (arguably the natural conclusion in an unofficial trilogy of epic animated musical films that build on one another and whose trajectory began with Beauty And The Beast) as well as another current stage sensation, Wicked, seems to have brought out the best in Menken during their three collaborations (he can do “fun”, too, as Enchanted proved). Pocahontas went deeper into language and spiritual themes both lyrically and musically than any other Disney film before, and the pair’s score for Hunchback maintains this approach, interweaving the songs into the score so much so that the original soundtrack release could not simply bunch the songs up front as is so often the case and had to play out each cue chronologically.

It really is a rich musical score, written for a Disney film or otherwise, and easily triumphs over the awful Notre Dame de Paris (using Hugo’s original book title) musical that I had the misfortune to suffer on the West End stage in London. Full of power ballads and bloated staging, the intention to ape the enduring appeal of that other Hugo musical adaptation, Les Misérables, was overabundant, whereas this Menken/Schwartz approach achieves that in spades just by focusing on the story and finding the right spots for music to convey the tone. Exuberant early on is Quasi’s Out There, essentially the hunchback’s “I want” song (during which Beauty’s Belle makes a fun but not ridiculous cameo), while Frollo’s Hellfire is a visual and musical highlight, making use of the imposing but majestic main four-note Notre Dame theme that Menken anchors to throughout.

From the start, it’s clear that this is Disney at the top of its game. Perhaps more than any other feature from the “tradigital” 1990s, the music merges with the physical animation to create a visual and aural feast full of various splendors throughout, from the enticing opening number to the use of computer mapped backgrounds that hint at the Deep Canvas technology of Tarzan to come, during the film’s immensely suspenseful conclusion. Going back a little, the gargoyles’ A Guy Like You is the film’s only true weak spot: coming late in the game, the song somewhat reverses the thought process behind Pocahontas’ deleted song If I Never Knew You while bowing to the same pressures. In that film, the mature and emotional tugging of the characters’ lives came to a head at this moment, the song allowing their feelings to be emoted – but at the cost of supposedly boring the kids in the audience.

Here we have something of the same issue, albeit much more emotionally tense than romantically overwrought. Various characters find themselves at challenging points of their lives at the beginning of Hunchback’s third act, and the situations are tightly stretched. Just as Pocahontas needed a song at this moment, to release all that pressure, what Hunchback definitely does not need is a song right here: a song that punctures all that pressure and lets the air right out of all the build-up. But it’s here that A Guy Like You comes, superficially inserted to calm the kids down and give them a bright comedy number inbetween all that adult character analysis and the impending doom they face, but coming across instead as if the pause button had been hit to provide a breather when one most certainly wasn’t needed.

It really does break the mood, and to add insult to injury A Guy Like You isn’t even inspired Menken/Schwartz, sounding as if an old tune from not only another musical, but a completely alternate tone of musical, had been dusted off and written for in a rush to fill a late-spotted gap. On it’s own, A Guy Like You might well have been a fun number in a lighter-hearted piece – indeed the very similar One Last Hope, from Hercules and which is possibly just as out of place there too, at least offers a chance to see how such a song would work better in an out and out comedy (so much so that they’re essentially interchangeable melodies). It’s interesting that both are also sung by wisecracking New Yorkers: Jason (Seinfeld) Alexander here and Danny DeVito in Hercules, offering a faux-Broadway pastiche performance in musicals that are anything but!

Indeed, when Disney’s Hunchback made its debut on the stage, it was in Germany and with a distinctly darker, perhaps more “European” take on the material, with less of the gargoyles’ comedy and a closer interpretation of events from the book, which ends far less happily for some. The much-delayed American version, which has been on the cards for over a decade now, has finally been recently announced as now being revised with a new book to include further new songs from Menken and Schwartz in addition to those already written for the show. Perhaps, with the continued success of Les Misérables on stage and in its recently praised but, in this reviewer’s opinion, mis-firing movie incarnation, Disney might have finally found a blockbuster stage production to match its own Lion King and give the legendary likes of Les Mis and The Phantom Of The Opera a run for their money and, hopefully, creating a bona fide musical classic into the bargain. Certainly a darker feel and less pandering to the potential child market helps the theatrical stage musical achieve these ambitions: the original film naturally had to bear in mind the fact that this was a Disney animated film after all.

But it’s clear the filmmakers had been influenced by Laughton’s 1939 classic: several shots clearly recall that earlier film, and the exuberance of Quasi’s rescuing of Esmeralda and cries of “sanctuary, sanctuary!” is matched by way of those elaborate, pre-Deep Canvas melding of character animation and background. Then there are the nice solutions made to the requirements of the story – yes, this is ostensibly a “children’s” film, or at least one that they can see, but Hugo’s novel is a pretty strange choice to begin with for this medium. It’s cleverness is in its deferences to Hugo: on revealing Quasi’s face in Notre Dame’s square, he is at first feared and sneered at, being slashed by Frollo in the Laughton film. Back then, in black and white, the hunchback’s blood, while deep and black, wouldn’t have shocked as much as had Disney allowed the same events to happen here. Instead, Quasimodo is pelleted with the marketplace’s fruit and vegetables, allowing a blood substitute to be found in a tomato’s juice, for example, as it explodes upon hitting its target.

With the aggressive tugging and slashing of Quasimodo’s clothes, the end effect is visually the same: he is degraded, scolded by Frollo and is such that he may as well have endured a beating. James Baxter’s animation here is striking: Quasi’s limping to the cathedral doors and his closing them representing a low point, emotionally, for the character. Likewise, at the film’s ending – instead of Laughton’s hunchback remaining in his tower (“If only I were made of stone like you”, he says to the gargoyles), Disney lightens things up with Quasi’s acceptance by the Notre Dame folk, by way of having a young girl, and not a cute and typical moppet but herself quite plain looking, touching Quasi’s face and finding that he’s not actually a monster (“What makes a monster and what makes a man?” is the film’s overriding comment). This is actually quite a clever substitute ending in that it is an innocent child who makes this discovery: no adult tries to stop her, but once she is content then they are easier with the hunchback too, and in a way using a child for the scene is not only a device for the town to appreciate him but for the younger audience to accept him without being afraid, too. I’ve always felt these were a couple of the most subtle but brilliant touches in a film full of such nuances.

On original release, the film was generally greeted with respectful reviews, even if they didn’t rave about the film completely, and the box-office made the film a $100m hit even if it didn’t smash the heights of what had come before. In some ways, Hunchback marked the beginning of the end of the 1990s Disney Renaissance, with only Tarzan and Lilo & Stitch putting up any resistance to the growing amount of CGI comedies that would soon account for the majority of animated movie programming, in a trend that continues to this day. In the same vein, it’s slightly ironic that Disney’s Hunchback has come along again just as Hugo’s other musical adaptation has been given a boost in publicity due to its film version being so well promoted, but I don’t believe that Disney’s Blu-ray upgrade has been issued at this time to cash in on being a musical “from the creator of Les Mis” since it’s merely the latest in the Studio’s rather rushed attempts to get the majority of their animated features out in HD before the format runs its course.

However, the passage of time has actually been kinder to Hunchback than it has toward other films of its age and, as is generally the case with Disney’s animated movies, the passing of the years has only solidified its reputation. Perhaps because of its setting and perhaps because more and more have woken up to the fact that it was a brave film to have made (then and even more so now), The Hunchback Of Notre Dame seems to now be regarded as something of a minor classic. For fans of the film that, like me, have been since the incredible shot of Quasimodo rescuing and holding Esmeralda aloft the cathedral, that has been tremendously gratifying to see, and this new HD edition, direct from the digital files, fulfills the visual promise that the film made back in 1996. I can only wonder if a more traditional Christmas release might have attracted a larger and even more appreciative crowd, but as a true artistic departure from the Studio norm, this is one of Disney’s most unique and admirable films. Please experience it.

Is This Thing Loaded?

Presented as a 2-Movie Collection, the only really lamentable aspect to this set is that it means suffering through the truly terrible direct-to-video sequel, The Hunchback Of Notre Dame II from 2002. Now…really…forget the fact that Disney’s theatrical motion picture comes close to being genuine animation art of the modern era and remember that the original novel is widely seen as one of the true great books, and a masterpiece of French Gothic writing. This just isn’t the kind the kind of title that should ever have something as crude as a “2” or, even worse as an attempt to lend the endeavor some kind of kudos, a roman numeral “II” placed after it! Totally disrespectful to not only Hugo’s book but also to the Disney film, you can pretty much take all my comments about the original and throw them out the window: The Hunchback Of Notre Dame II (ugh!) is just excretable crap!

There was a time when the Disney DTVs picked up the “cheapquel” nickname, and Hunchback II is perhaps the epitome of why the Studio’s sequel films earned that title. Unfairly dubbed on some of the films to emerge from what would become known as the DisneyToon Studios (primarily a facility in Australia but with satellites dotted around the world in Canada, France and Japan), these DTV titles never lived up to their original inspirations, but at least some of them made attempts to be worthy entertainment. Of course, no-one was clambering for follow ups to Walt’s originals of Lady And The Tramp, The Jungle Book or Bambi, but some of the resulting efforts provided a better than expected experience. More modern fare also got sequels, such as The Lion King, Mulan and Lilo And Stitch: none of them too embarrassing while purely remaining confined within their limited direct-to-video ambitions.

Some of these titles – such as a pair of Goofy movies and a return to Never-Land for Peter Pan – even approached true theatrical quality, but on the other end of the scale, the likes of follow-ups to Cinderella and Pocahontas were easy targets that the cheapquel-bashers could hit all too easily. These films were bottom of the barrel, forgoing much reason to exist in terms of animation, story progression or song quality, other than to come out on videocassette or DVD and make a quick buck off the back of the release of the original movies. There are still various elements to either enjoy or even applaud in quite a few of these titles, but there are also a handful that truly never deserved to exist, being less than half-baked, uncharacteristic and plain ugly additions to Disney’s otherwise spotless animation legacy.

Firmly and squarely in this category fits Hunchback II, an abhorrent black smudge among even the worst of the Disney DTVs, and quite possibly – considering the elaborate art of the lush original film – absolutely the most unpleasant of these films. From the opening shot, crudely drawn with very noticeable keyframes and seemingly ink and painted with magic marker pens, one can almost hear the groans of Wise, Trousdale and Hahn creaking from the soundtrack: this is the legacy of their original film!? The music does what all bad DTVs usually do, playing hyperactively in an attempt to paper over the cracks and make everything feel “fun” and better audibly than things are visually. Oh, and what visuals! No, no…I mean what visuals!? Reeking of a “quality” less than acceptable on Saturday morning television, this is perhaps Disney’s most embarrassing animation moment.

“Crude” really is the only word I can think to describe it, although I’d need to repeat it ad infinitum for it to even begin to register just how poor this is. “Plot”-wise things are no better: although thankfully, at least, this doesn’t revert to typical DTV fare to create an early “mid-quel” life for Quasimodo as he grows up as a young boy in his tower, choosing to provide a more suitable additional story that takes place after Frollo is long gone and Quasi is free from his foreboding master. Free from any kind of dramatic force as well, it seems, for Hunchy II seems content to just play with a lame, half-assed notion of finding someone to love Quasi in an attempt to hammer home the “people can be different” moral. This is done via a visiting circus, in which the twisted ringmaster of sorts, Sarousch, has this insane idea to try and steal one of Notre Dame tower’s most elaborately jewelled bells, while torn between this plan and her growing feeling for the hunchback is Madellaine, a jobbing Jennifer Love Hewitt who deserves better than being offered this trash.

As Sarousch’s (Spinal Tap’s Michael McKean, barely recognizable) scheme plays out, and Mads slowly falls further for Quasi (blah, blah, blah…), the outcome is never really in question, and I dare the more mature among you (especially the big fans of the original movie!) to even get to the end of this without ripping out your teeth and eating your own head with them. Quite how the original voice cast of Hulce, Moore, Kline, et al, were tempted to return – in all seriousness, were they bribed? – is a mystery. I can only imagine that they didn’t understand that the animation would not be handled by the more talented teams down under or in Canada but by the television department in Japan, farmed out to various local studios more used to churning out weekly series episodes intended to be quickly consumed and forgotten rather than having to compete – on any level – with one of the Studio’s most lusciously visual outings of recent times.

Can you tell that I hated this one with a vengeance yet!? Given the poor, poor feedback that I’ve often heard about Hunchback II (oh, just how wrong is that title!), it’s one of the very few of the initial batch of direct-to-video releases that I never saw. I did actually catch a good few minutes of it on a TV showing some years back, but couldn’t make it past half-way and mourned the day I would inevitably have to sit down and review the whole thing. All I can say is that it truly does make the likes of Cinderella II look like a masterpiece. Is there anything redeeming about it? Well, however long its cheap and nasty 60-minute running time (easily adequate enough to inflict permanent damage) feels, it does eventually end. But this isn’t a recommendation: even at just over a scant hour or so, I genuinely hope you never feel the urge to try this out: you will endure a hellish version of childish Disney animation that will make you want to burn your own eyes out of their sockets. Remember: I reviewed this so that you don’t have to!

Making this 2-Movie Collection even more of a disappointment is a total lack of additional extras that provide anything new, or at least do anything more than just repeat the handful of supplements from the previous DVD edition. The one downside to Disney’s fast-forward approach to updating their DVD catalog to Blu-ray has been the reliance on only the most recent previous edition of a title in the extras department. Some films that enjoyed deluxe two-disc releases but later found their extras dropped in a single disc reissue have not had those earlier supplements reinstated for Blu-ray, a sorry state of affairs when one must conclude that these releases should represent their most definitive editions. That they are most certainly not is emphasized by Hunchback’s meager helpings when so much more was easily available and could have been included (especially over the redundant waste-of-space sequel if that had been the case).

What we do have is “another chance to see” the 1996 television special The Making Of The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, hosted by Jason Alexander and running around 28 minutes. As a half-hour TV special, this does the basics of covering the production well, and it’s a solid inclusion itself even if Alexander’s moments are a little too mildly flippant in discussing the otherwise sombre movie the special is focused upon. But soundbites from cast and crew offer a peek behind the scenes, and those coming to it new will find all they need to know and see here, although many will remember it already from the LaserDisc and previous DVD discs. Also cribbed from the original LD is a full-length Audio Commentary with Hahn, Trousdale and Wise, who bring their usual jovial tone to their intelligent remarks in another terrific track (after Beauty And The Beast) that entertains just as much as it informs.

Lastly – yes, lastly – for the original movie, the A Guy Like You Multi-Language Reel (3:20) offers up brief examples of how the movie was dubbed into various international dialects. I always find these things kind of amusing, since sometimes an unfamiliar language can suggest words and sounds totally unlike one is used to hearing on a well-known track, but the choice of out-one-out song A Guy Like You doesn’t really offer up the best examples of differences. From the sequel’s DVD, the Disney Channel Movie Surfers’ Behind The Scenes With Jennifer Love Hewitt (4:50) may be the best way to glimpse moments of the movie without having to watch the full thing. Finally, A Gargoyle’s Life: It’s Not Easy Being A Gargoyle (2:40) is more fluff, the worst aspect of which being that it subverts shots from the original film rather than the easy target sequel.

On the enclosed DVDs – which are exact duplicates of their previous editions, right down to the dated previews – The Making Of The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, Commentary and A Guy Like You Multi-Language Reel both feature alongside a silly soundmixing game and sing-along, while Hunchy II gets the Behind The Scenes With Jennifer Love Hewitt featurette plus A Gargoyle’s Life and set-top game. Across all discs, the usual Sneak Peeks feature for The Little Mermaid’s 3D Diamond Edition,Monsters University and the full trailer for the semi-Pixar-less Planes (a smart move on their part: if it’s a hit they can say it was inspired by Cars, if it flops then it’s all Disney’s fault for stretching out the franchise), plus previews for Epic Mickey: The Power Of Two, Mulan, SuperBuddies, Return To Never-Land and the next, untitled Tinker Bell outing amongst other Disney promo spots.

WHAT’S MISSING?

The real disappointment here in terms of extensive supplements for such a significant film in the Disney library is that a two-disc DVD set was announced and then mysteriously pulled soon after the announcement, although I do believe some cover artwork did make it out into the webisphere. Quite what this release would have included was never acknowledged but it’s a fair bet that it would have included most if not all of the previously released deluxe CAV LaserDisc boxset edition, and perhaps even more. Over the 90 or so minutes of LD supplements (which included the Making Of), fans were treated to a myriad of extras bonuses stretching across the production, from an Early Presentation Reel of concept artwork and music and three Deleted Song storyboards for Someday, In A Place Of Miracles and As Long As There’s A Moon, with optional commentary by composers Menken and Schwartz, to a pick of Theatrical Trailers from the film, plus what I believe might have been an alternate Multi-Language Reel (this could have been A Guy Like You as featured here but my recollection tells me it was for the opening Bells Of Notre Dame sequence). In addition, information was presented on the History And Background Of Notre Dame de Paris, including author Victor Hugo, as well as on the History Of The Production Of The Hunchback Of Notre Dame.

Nine Character Design sections highlighted concept and final designs for Quasimodo, Esmeralda, Frollo, Phoebus, Clopin, the Gargoyles, the Archdeacon, Djali, and Miscellaneous Townspeople and Gypsies. Two Story Reels were presented, for The Bells Of Notre Dame and Heaven’s Light/Hellfire, as well as Workbook And Scene Planning examples, and more on the Art Design, Layouts And Backgrounds – all of which included multiple image galleries. Further sections on the Animation, the integration of Computer Generated Imagery and a final Publicity gathering of images completed what was a very satisfying set. With Disney having practically dropped their image galleries from their Blu-ray editions of late, one could predict that these wouldn’t make the cut, but surely the other material could have been re-assembled, even if it was transferred from the LDs themselves!? And surely there must be someone there at the Studio that could have combined the stills into video slideshows, perhaps with the score as accompaniment? With everything available to them, it’s a shame the producers of this disc didn’t dig deeper: even if only presented in standard definition (as all the extras are anyway), it would have made for a much more complete package and a proper salute to this distinctive film. As it is, this BD very much feels like a slapped together grouping of what was lazily available.

Case Study:

Even Disney doesn’t really want to associate itself too closely with the animation atrocity of The Hunchback Of Notre Dame II, wisely and oh-so thankfully choosing to not make this set’s sleeve one of those dual-sided efforts that showcase both films side-by-side on the front cover. Going for, instead, one of the greatest mood posters yet devised by the Studio for one of its 1990s outings, The Hunchback Of Notre Dame gets one of the classiest slipcovered releases of the Blu-ray era, recalling the similar treatment the film received when it debuted in its deluxe LaserDisc edition.

Past home video releases of Hunchback have explored the singing or adventurous aspects of the central characters, but none of them has ever nailed the film’s tone in their cover art, so it’s terrific that this version returns to an image of Quasimodo sitting in his bell tower that doesn’t try and sell the movie but just suggests its tone. Okay…so it’s true that, in an attempt to lighten the mood somewhat and appeal to a slightly younger set, that the three gargoyle characters have been added to the fringes, but it has to be said that it’s been tastefully and almost transparently done with them buried in the shadows.

Ink And Paint:

Now this is an interesting one… Having only seen Hunchback on home video via a film transfer on the LaserDisc (I never did see the DVD), this new digital edition, seemingly direct from the digital files, looks a little lifeless to me. In actual fact it’s the best the film has ever looked, but something of the clinical nature of the absolutely rock-steady image has kind of taken something away from the Gothic, grungy and more earthy feel of the old film prints. Color is stable and vibrant throughout, and the film’s animation – among the best and most delicate of any Disney feature – is detailed and shown to its best advantage; the standout musical number Topsy Turvy looks incredibly pixel perfect. However, there’s a bit of “depth” missing, perhaps, from what I recall from the print, and one or two shots where perspective doesn’t quite work when a character enters the frame. This is probably more to do with the artwork than the transfer, but the complete lack of grain, I feel, takes something away from the cinematic qualities that I associate with the film. That’s a personal view, naturally: in all other respects, The Hunchback Of Notre Dame looks phenomenal.

As far as the sequel goes – well, it seems even the Studio knows it has a complete dud on its hands (in fact, does Hunchback II warrant the award for worst Disney animated outing ever?), as it hasn’t even bothered to give this one a remastering. As if the visuals weren’t bad enough already, Hunchy II sports the complete opposite of the original film’s digitally perfect look, coming from a spotty film print covered at times with debris. Is anyone really going to care? Well, while I believe any film deserves to be seen as optimally as possible, Hunchback II doesn’t actually deserve to be seen at all, and so it gets the perfect treatment here. In a 1.66:1 transfer, the widescreen does nothing to elevate the truly cheapquel feel – it’s bad, bad, bad, and the only great thing is…Disney knows it!

NOTE: the frame shots shown here are from the DVD editions in this set and are for illustrative purposes only; they do not represent the quality to be found on the Blu-ray Disc.

Scratch Tracks:

A truly high-end production, Hunchback benefited from a totally elaborate post-production treatment so that the soundtrack’s many…um…bells and whistles matched the intricacies of the visual artwork. Although less action orientated than today’s mixes, the film enjoys some wonderful atmospheric touches even given the musical confines: vocals have been tweaked to sound as if they are outside, inside, in a bell tower, cathedral or wherever, and the effect is always natural. The music shines, Menken’s chorus coming at us from all directions, the sound doing what all good tracks should and assisting the storytelling fully. It’s a great track given a great chance to play as intended here, unlike the dull and regular feel awarded to the video sequel where, although the vocalists give it all they’ve got from what they have to work with, a fully enveloping feeling of life never threatens the proceedings.

Final Cut:

The lack of extensive extras disappoints absolutely, especially given that a two-disc DVD set was on the cards at some point in the mid-2000s, and the inclusion of a video sequel – even if it is “free” – might actually be the first time that a supplement (and that is exactly what it is) is responsible for a set losing points in an overall score! That being the case, we must overlook this crime against Disney animation quality and re-focus our attention to the genuinely worthwhile original…a film that, perhaps, was the last time the Disney Studio really took a risk. It certainly came at a prolific time for the Studio, when all kinds of animation techniques were in effect, and was a brave subject to tackle. It’s telling most of the animated films to come since then have been CGI comedies, and one just cannot imagine that process ever conveying the complexities on show here. Making a damn good case for traditional hand-drawn animation to continue to thrive, The Hunchback Of Notre Dame deserves a ranking among the best of Disney’s 1990s pictures.

| ||

|