Arthur Christmas is Sony Pictures Animation’s first film collaboration with Aardman, the landmark animation company best-known for their award-winning and crowd-pleasing stop-motion films Chicken Run and Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit. The winners of over 400 international awards, including four Oscars (three for Best Animated Short Film, and one for Best Animated Feature Film for Were-Rabbit), Aardman delivers their second CG-animated project with Arthur Christmas, and takes on an ambitious subject: the delivery of two billion presents in one night.

Arthur Christmas is Sony Pictures Animation’s first film collaboration with Aardman, the landmark animation company best-known for their award-winning and crowd-pleasing stop-motion films Chicken Run and Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit. The winners of over 400 international awards, including four Oscars (three for Best Animated Short Film, and one for Best Animated Feature Film for Were-Rabbit), Aardman delivers their second CG-animated project with Arthur Christmas, and takes on an ambitious subject: the delivery of two billion presents in one night.

In taking on a project with the scope and scale of Arthur Christmas, Aardman – a company best-known for the clever humor and idiosyncratic designs of its signature stop-motion films – took on a great challenge: how to translate the characteristic Aardman sensibility to a 3D-computer animated form.

“At Aardman, we always say that the house style is in spirit more than anything else,” says Peter Lord, a producer of the film and a co-founder of Aardman. “We like to make different sorts of films. This one was radically different than anything we’ve done before – different because it’s CG, of course, but also different in scope, different in design, and different in its style of writing. It’s very skillfully detailed, verbal, witty, and clever. But we’re happy with the ways it’s different, because it still feels very much like an Aardman film at its heart.”

The project became a merging of the minds between the storytellers at Aardman, the creative animation team at Sony Pictures Animation, and the CG artists and technology at Sony Pictures Imageworks and Aardman. Bob Osher, president of Sony Pictures Digital Productions, says that the animation studio’s unique expertise made it a perfect match for Aardman. “It was extremely important to all of us that every nuance and character trait that is unique to Aardman’s style of animation be facilitated as the project moved into the digital pipeline,” says Osher.

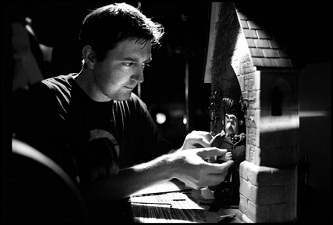

No doubt about that as the Supervising Animator of the project was no other than Aardman veteran Seamus Malone. After his studies at Ballyfermot Senior College in Dublin, he joined Aardman Animations where he soon became Key Animator on Rex the Runt, Chicken Run, Creature Comforts USA, Creature Comforts 2, The Curse of the Were-Rabbit and Wallace and Gromit’s A Matter of Loaf and Death. He then became Director of 17 episodes of Emmy and Bafta winning series Shaun the Sheep (who makes a cameo in Arthur Christmas!) and in 2002 he moved into CG at PDI/DreamWorks to take part in CG training and character acting development for Shrek 2, which led him to animate for Aardman on Flushed Away, and then for Arthur Christmas, now as a Supervising Animator.

Animated Views :Mr. Malone, your studies were in traditional and stop frame animation in Dublin. What led you to the art of animation, and to stop frame animation in particular?

Seamus Malone: I think I was led to animation just by my own love of cartoons and trying to figure out how they moved, then I discovered flipbooks and started decorating a lot of my schoolbooks and copybooks and that’s where my interest in hand drawn animation started. I was always interested in making things too, out of wood or clay or anything, and this made me want to do stop-frame animation as it involved animation technique and a lot of miniature set building

AV: To you, apart from the technique, what differenciates stop frame animation from the other forms of animation like, say, hand drawn animation?

SM: I think stop-frame animation still has that hand-made tactile quality to it. People can look at it and go, ‘I could try that, I could have a go at that’ even if it’s just a lump of plasticine. And also they are real three-dimensional puppets, they live on a real set, a stop-frame set is like a live action stage, just in miniature. You don’t have to re-draw the character each time like in traditional hand drawn animation, you just get your hands on the puppet and go!

AV: How did you get to Aardman? What are your memories of the studio at that time? Regarding the films you took part in, what are your best memories?

SM: I started working at Aardman in 1996 when they were thinking about doing a feature. They ran an animation training course for a few months which I was lucky enough to get on then I started working on a lot of stop-frame commercials. There were a lot less people back then and less departments, some people had more than one job title! Then we started working on the beginnings of Chicken Run, I have great memories of that film because it was the first feature we had ever done and nobody really knew the proper way of doing things, we made stuff up as we went along on how to make a feature film, but we learned a lot too and it was great training ground for everyone involved.

AV: To you, what makes Aardman special?

SM: It’s the humour and the people, the team that you have around you, theres often a quirky absurd type of humour on different shows here that comes across in the character design, sets and the character acting of the animation.

AV: How was it decided to get into CG animation?

SM: Aardman has always had a CG department since I arrived and it was well established with the commercials department. When Flushed Away was being pitched, the amount of water and the scale of the underground city would have been limited in traditional stop-frame; it had a much bigger scope and scale than previous films so it was decided to try CG then for features.

AV: Can you tell me about your training at PDI, on Shrek 2. What interested you in that new medium?

SM: I went to PDI with another animator from Aardman in a DreamWorks-Aardman training scheme, we were all sort of on a boot-camp in preparation for the next Shrek. We kicked around a lot of ideas with the animators there, experimented with shooting on double frames, and approaching the acting in a different way with lots of acting out scenes in a group before we even started to animate. Me and my colleague also taught some stop-frame techniques to the CG animators there, which I think helped the animators to think about three-dimensional space a bit more. A lot of the animators said it broadened their knowledge of 3D space in animation, thinking about stop-frame and CG.

AV: Animation-wise, how did you keep the Aardman touch through CG?

SM: Well, the design of the Flushed Away characters was fairly recognisable with the eyes close together and the big wide mouth. On Arthur Christmas , we made sure that none of the characters were too perfect, they were all a bit asymmetrical, one ear slightly higher than the other, rough skin and wrinkles in the right places, all flawed in some way in their appearance. And of course the humour in the writing has a very British feel to it.

AV: How would you explain your role as supervising animator on Arthur Christmas? What does it mean in terms of a work relationship with the animators, and with the director?

SM: As one of the supervising animators, I had to check in daily with any animator that was working on any one of my sequences. We would talk about the best and funniest way to play out a scene and try and sort out any problems, maybe act it out a few different ways before the first pass was shown to the director. Sarah, our director, didn’t have the time to go around to see every animator individually so that’s where I came in. Sometimes I would have 10 or even 20 animators to check in with so the day went very fast!

AV: Did that new partnership with Sony change anything for you?

SM: It introduced me to a very talented bunch of people! There were a few different animation tools to get used to, but that was all. I had to relocate from Bristol to Culver City with about 16 other Aardman staff so we brought a little bit of the Aardman community to Sony.

AV: Can you tell me about your process when approaching a scene? How do you prepare it? In what way does your hand-drawn and stop frame animation background help you in your work?

SM: Everytime I approach a scene I act it out quite a lot of times, I want to be able to understand the performance as an actor (even though I’m not a great actor!) and when I feel I have it, then I can start to translate that performance into a puppet, whether it be a stop-frame 2D or CG character. If there’s quite a few shots in the scene, I will act out the whole scene, not just the individual shots. We record some of these performances too, not to copy but just to look at once or twice a day while animating as a guide.

AV: In terms of expressing emotions, is the approach different depending of which form of animation you use?

SM: I don’t think the approach is different, you want the audience to believe and care about your character, no matter what medium you are animating in, you want the performance to stand out, the timing and the acting, whether it’s a funny scene or a more emotional one.

AV: What were the challenges of the animation of Arthur Christmas?

SM: I think the mission control scene was quite technically challenging for me in that there were so many elves and things going on in the background. Acting –wise the scene near the end when all the Santas are in the cloakroom was a great challenge for me and the rest of the animators on that scene. It was all about stripping out as much as we could, just holding the characters in amazement when all of their emotions are running so high, I think I used to give a note of ‘not to animate’, keep everything as still and subtle as possible to hold this moment and not break the feeling we were going for.

In the dinner scene, we had to work out the logistics of the board game they are playing, whos go it was, what square to land on, what the dice rolled, which all had to fit into their dialogue at the same time! We went around to the director’s house one night and decided to re-enact the scene with a rough version of the boardgame just drawn on a big sheet of paper while coming up with the rules of the game!

AV: What is your animation process like?

SM: I like to give an animator a string of shots together so they have ownership and continuity of acting over that little scene, but sometimes the schedule dictates that you have to spread five shots over five different animators which is harder to keep track of sometimes because every animator will do the same thing slightly differently. At the same time, I will always make sure the animators are aware of who is animating the shots before and after them. In some shots there were so many elves, we had to split the shot up so that everyone done a little bunch of elves rather than the same person having to animate them all.

AV: You’re now back in England. Is it important to you to keep working close to your homeland?

SM: I’m actually from Ireland but I’ve been living in Bristol for a long time. I think you can travel around quite a lot in animation anyway, although I do love the European side of the world, I do miss the sunshine of California a bit! Aardman of course is well known for its stop-motion and that is going stronger than ever here, and with Arthur we are starting to do more CG. The movies from all the US studios are as inspiring as ever but I think there’s room for it all, no matter what part of the world it comes from.

AV: Do you think that this bond between England and America on Arthur Christmas helped make a one of a kind film?

SM: Yes, a lot of the Sony crew came to live here in Bristol at the beginnings of the film when it was being developed and we took it upon ourselves to show them the Bristol way of life! And then a bunch of us Aardman folk went over to LA and the favor was returned, so there was a bond there that I think helped make Arthur Christmas a unique film in itself.

AV: What project are you working on next?

SM: I am currently directing some new Shaun the Sheep episodes, a stop-motion TV show that we do here at Aardman about the woolley adventures of an inquisitive sheep and his flock!

Our deepest thanks to Seamus Malone and Olivier Mouroux