Jeremie Noyer continues his multi-part discussion with Mark Henn, presenting a new chapter each fortnight in celebration of the worldwide launch of The Princess And The Frog from the US release to its European debut, and evoking the chronology and different aspects of the veteran animator’s career, from his studies and dreams of working for Disney, to his first assignments and serving as supervising animator on the Studio’s current contemporary classic!

Disney’s Floridian animation studio is famous for the three animated features they produced, Mulan, Lilo & Stitch and Brother Bear, that held a very special position within the Disney pantheon. Mark Henn was part of the first two of them, and especially had a major hand in Mulan.

In this third part of our discussion with him, we talk about what made that experience so special.

Animated Views: The launch of Mulan, the first full-length feature to be entirely produced at the Florida studio, must have been a great event!

Mark Henn: Oh, it was great news! Mulan was a great story for us to start with. I really liked it. It was a very long experience for one thing. It was similar to what I did in the past in a lot of ways since it was another leading lady for me, but what her story was about was so unique and so compelling that it just captivated me from the beginning. Certainly, for me, one of my greatest memories was the simple fact that a group of us was able to go to China for research. To have an opportunity to do that was pretty amazing as far as I was concerned. We spent almost two weeks there, meeting with the people, seeing Mulan’s world, meeting her people, meeting experts and people who historically knew the story of Mulan. She was so popular in China, her story is so well-known there that I felt as a great honor to help bring her story and her character to life. That, to me, was very exciting. That was definitely one of those once-in-a-lifetime experiences that a lot of people just don’t get to have.

AV: In what way did that research trip in China nourish your approach to this character?

MH: Well, I saw the land that she saw. I saw in the people of China the respect for her story and who she was. There is a lot of history and tradition there and she fits in all that: that was very inspirational to me. More than anything, everywhere we went, when you mentioned we were working on the story of Mulan, people’s eyes just lit up. So, it was of great importance to me to make sure that she, as a character, was everything, hopefully, that the people of Chine, who grew up with this story, wanted her to be. That was a real challenge.

AV: Another challenge certainly was to deal with her transformation into a man. How did you deal with that?

MH: That was certainly a unique challenge with her, too. When we drew her, we had the opportunity to actually adjust her design a little bit so that when she was disguised as Ping, as a soldier, that she was physically a little different in how we drew her than when she was herself as Mulan. That’s something you probably wouldn’t be able to do in live action. That was something we took advantage of. So, certainly, that was a challenge to have her disguised as a boy whereas she’s still a girl who doesn’t understand what being a boy is all about or about boys move and act, and that’s part of how she learns. She’s getting instructions from Mushu along the way – some not-so-good instructions – but that was part of the fun and the challenge of doing Mulan. You have essentially two characters to play with.

AV: Was the challenge more difficult than in the past?

MH: It was mostly interesting. I wouldn’t say it was difficult. It was definitely interesting. Again, what she did had to be believable so that the audience accept the fact that this girl disguised as a young man is trying to stick into the army, essentially to save her father’s life.

AV: Speaking of Mulan’s father, you animated him, too. What was that like?

MH: You know, I am a father. I have a daughter, and I guess I drew, if you will, on a lot of that emotion. That was kind of the source for a lot of what I was thinking about as I animated her. I ended up doing that because the directors came to me and they said that they needed this relationship to work. So they decided to ask me if I would be interested and I said “absolutely” because I agreed that’s the emotional heart of the story, her and her father. If that didn’t work, we would have no movie.

AV: The way you brought this relationship to life is incredible. I don’t remember such a deep relationship expressed that way in the whole of animation history.

MH: Thanks. That’s the nicest compliment an animator can get. I’m no expert but having the opportunity to see how relationships work in China plays a big part in that success. I don’t want to say that they don’t have emotions but they keep their emotions. There’s a lot of honor involved in China and in Chinese families. There is rank, there is respect for elders. Mulan understood that but she felt that the circumstances were so extraordinary that she was willing to kind of fly in the face of all that tradition in order to essential uphold the tradition and protect her father’s honor, which was a very complicated emotion. That was very exciting to try to pull that off.

Her father represented all that tradition and honor, although he loved his daughter deeply. He took that honor to its limits and at the end of the last sequence when she comes home and everything is out now and she knows that he has every right to basically club her for doing what she did, potentially disgracing the family. Then, his love for her exceeded that honor, that stoic position and he allowed himself to step out and just express his deep love for her. As a parent, we all feel that way for our kids – at least I do. That gives you goosebumps talking about it. That was the emotional heart and soul of the film and that had to work. If it didn’t, you just didn’t have a story.

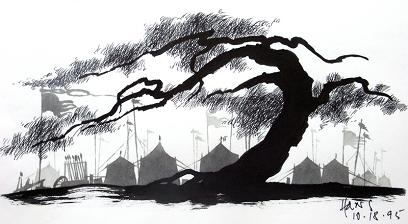

AV: The subtlety of these emotions fits perfectly the very pure design of the film, inspired by Chinese traditional art.

MH: In my mind, I don’t think you could have told that story without paying tribute to the incredibly rich artistic tradition and elements that you find in China. That was part of our trip over there: seeing all that and learning about that. You just couldn’t ignore it. We had a terrific actually Taïwanese artist named Chen Yi who was very inspirational in helping to come up with these designs. We learned about the historical context, the art, we went from one dynasty to another – looking at the art is one of the ways they can identify the various Chinese dynasties. I’m really glad we had that chance and I think everybody on the film worked very hard to incorporate that without it becoming a documentary. That’s always the balance: we’re still making a piece of entertainment. But I think it’s the level of research and detail that people expect in our films making them much believable.

AV: Was this delicateness of Chinese art a problem in expressing strong emotions in your animation?

MH: That’s always the struggle that you have when you animate these films. We don’t create realism in the sense that if you’re doing a human character, it’s not going to look realistic. But the balance is finding an appealing way of drawing using the visual tools that you have in the design to convey the believable emotions that you want to get across. It’s just a matter of finding kind of the visual language you need to use with your characters. Once you’ve found that visual language, then it’s just a matter of understanding and making appropriate designs that are appealing but that communicate the emotion that you want. It’s easy to make a very ugly drawing that looks realistic but it wouldn’t be very appealing. That’s always the struggle that we face on any of our characters, but particular on human characters. That’s seems to be a greater challenge.

AV: Then, continuing your exploration of traditions, you animated the beautiful hula sequence of Lilo & Stitch.

MH: That was a very poisoned surprise. I was initially going to animate Stitch in early talks with the production. But at that time I was deciding my life needed to move back to California. So, after ten years in Florida, I came back to California so I couldn’t work on Lilo & Stitch. But they called me after I had got back here and said: “would you be interested in animating these hula dancers at the beginning of the movie that we have?” And I said: “Sure. Absolutely. I would love to do that.” So, I had that opportunity and that was a lot of fun. They had shot some wonderful footage of authentic, not the kind of touristy luau kind of dancing that you normally would see. They had done their research as well, working with authentic Hawaiian dancers and hula dancers so that was a lot of fun and a great opportunity to be, even in a very small way, a part of Lilo, which I’ve always thought was a really fun movie. But I came back to work on Home on the Range, which is the next film that I worked on.

• In Part 4, we’ll talk about Mark’s taste for America’s history and his involvement in John Henry and Home On The Range.