Walt Disney Productions/Walt Disney Feature Animation (1940 and 2000), Walt Disney Home Entertainment (November 30 2010), 2 Blu-ray Discs plus 2 DVDs, 125 and 75 mins respectively plus supplements, 1080p high-definition (original 1.33:1 and 1.78:1 aspect ratios), DTS-MA 7.1 and Dolby Digital, Rated G, Retail: $45.99

Storyboard:

Hear the pictures and see the music as several classical selections are given visual interpretations by Walt Disney and his animators, a concept that was repeated at the turn of the millennium in a second film by the new generation of artists. This collection gathers both efforts, with many caveats…

The Sweatbox Review:

“Fantasia will amaze-ya” suggested the publicity for one of the film’s many releases over the years, but going by some of the disturbing choices and wasted opportunities this new collection throws away, Fantasia is just as likely to dismaze-ya too.

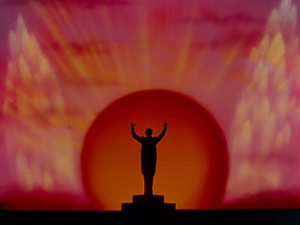

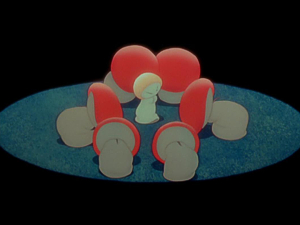

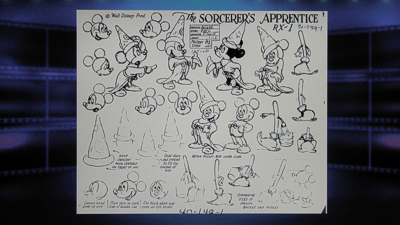

We all know the stories behind Walt’s grand, experimental “Concert Feature”, an attempt to really show that animation was art by tying it to the undisputed bastion of high culture: classical music. At a dinner one evening in Hollywood, Walt was approach by eminent conductor Leopold Stokowski, seen as something of a maverick in musical circles, though equally eager to see his art accepted by the masses too. The Disney Studio had been in production on a Mickey Mouse vehicle The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, designed to bring a little lustre back to the Studio’s star character, whose popularity was on the wane.

With Stokowski on board to provide a suitably impressive musical accompaniment from Paul Dukas’ original classical piece, the film’s budget soon ballooned to more than a typical short subject would be able to recoup. Stokowski suggested not cutting costs but expanding the project to include further selections of musical pieces, some of which would be “popular classics”, some of which would be more avant guarde. A final choice was made, and Fantasia became Disney’s third animated feature after Snow White and Pinocchio.

Walt’s hopes were high: here was a chance to showcase animation as an art form, though not for the last time was a lot of time and money spent on delicately animating the picture and chasing technical innovations that would ultimately mean the film couldn’t make back its production costs, at least initially. And this is where the discrepancies in Fantasia’s many reissues – and this latest presentation – come in: the film originally being designed as a touring road show that would visit cities and revisit in the coming years with new segments in place of others.

In order to make this even more of an “event”, Walt wanted to present Fantasia in a very special way, developing ideas for a “wide screen” approach to the visuals that would be twice the width of the then-standard Academy ratio of 1.37:1 and pushing ahead with the first use of multi-channel sound in order to have the audience feel the musicians were there playing live. Motion picture sound was still in its early years and only just about to become a teenager, and the quality just wasn’t that good. Signal noise and distortion were the biggest problems, but the mono soundtracks just didn’t convey the spread of an orchestra.

Knowing the images were going to cost more than projected, Walt reluctantly dropped the wider ratio screen idea to focus on making Stokowski’s music, performed by his Philadelphia Orchestra, sound as good as the pictures were going to look. The result was Fantasound, a system that pre-dated the surround sound set-ups of today, but also one that needed installing in each theater that played the film. Specific engagements were booked, but critical reaction in 1940, which focused on trying to knock Walt off his perch after his phenomenal success so far and suggested he had gone high-brow, kept many audiences away, and the beginning of World War II in Europe meant that market was closed for revenues.

Walt was crushed personally, and with the United States eventually joining in the war effort, the Studio found itself commandeered to making Army films, struggling to keep open by making purely commercial frivolities, or “Package Features”, that compiled several shorts into full-length pictures by way of linking material. These films interestingly didn’t break away from the Fantasia ethos, with the likes of Make Mine Music and Melody Time described as a “poor man’s Fantasia”, “a pop-music Fantasia” or “Fantasia for the masses”, with popular radio personalities giving voice to bouncy rhythms and upbeat stories. Walt had, in effect, created the music video.

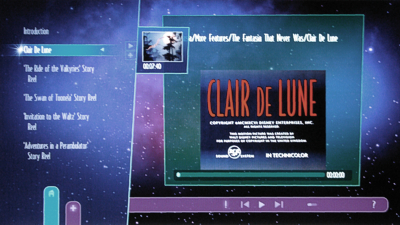

Clair de Lune, the lovely, lilting dreamscape composed by Claude Debussy, had been developed for the first of the intended continuations of Fantasia, and was in full animation by the time plans for more sequences had faded, was reversioned into Make Mine Music as the Blue Bayou segment, but ideas persisted for more Fantasia ideas that would never come to fruition. Picked up by Disney’s distributor in 1941, RKO made numerous cuts to the film, bringing it down from an original two hours and twenty minutes (including a fifteen minute intermission) down to the more regular animated feature length of just 81 minutes, cutting out music authority Deems Taylor’s interstitial introduction segments entirely!

Various editions followed between reissues in 1946 and 1969, when the film was sold to the counter-culture as “the ultimate trip” and was eventually profitable. By now, much of the Taylor material had worked its way back in, though topical cuts were made to remove a black centaur that was a clear racial stereotype. This cut removed the original intermission segments to run the film through in one sitting, shorter than the 125 minute road show version (minus the intermission) by around ten minutes. A reissue in the 1970s was how I was introduced to Fantasia, not in a theatrical screening but through the nefarious means of a bootleg VHS (with the black centaur scenes intact).

With the film having finally made some money, around this time work was proposed on a new version of the film, or at least a new music-inspired project, called Musicana. Although various stories and selections were made, the Disney brass didn’t have much faith in the idea, and the project was shelved. The idea of Fantasia didn’t go away completely, however, and a new print of the film was re-scored by Studio arranger/conduction Irwin Kostal, who recorded a new digital stereo soundtrack, much touted in the publicity for Fantasia’s 1982 reissue, but derided by the purists that, by now, were heralding Fantasia as the masterpiece it was.

By the film’s 50th anniversary in 1990, the new Studio regime of Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg were on a roll with reissuing the classic animated in theaters, and Fantasia was granted a full-on, chemical restoration for another big screen release that saw the film revised yet again, though into something that followed Walt’s original intention, with Deems Taylor and Stokowski’s music intact, as well as the usage of the intermission scenes used as the backgrounds for an end credit sequence that finally gave Fantasia’s artists the recognition they deserved.

Originally presented without a main title, Fantasia’s title card appeared on the screen throughout the intermission: without that break now in the film, this too was used, moved up front as an introductory card, which worked very well. One year later, Fantasia became the first major Disney feature to make its way to home video, with much fanfare…and phenomenal sales. The film sold so well, in fact, that Katzenberg went on television to announce that, “In 1996 or 1997”, a new Fantasia, in keeping with Walt’s original vision, would be released. Disney animation naturally exploded throughout the 1990s, leading to expansion in many areas, and the new film was created as a series of short subjects that would be worked on between the features.

Eventually, Fantasia Continued as it was originally known, would not be completed until late 1999, when it became Disney’s millennium milestone, Fantasia 2000 with a live symphony orchestra providing the music for its exclusive premiere. Bringing some prestige to the event of releasing the picture, it was exclusively debuted in Imax theaters for the first few months of the year, before coming to regular 35mm screens in the spring. As was the case with all of the contemporary Disney features, Fantasia 2000 was released on home video, to the DVD format, along with Walt’s original film, in an absolutely wonderful collection entitled The Fantasia Anthology that packed in a wonderful assortment of bonuses.

Interestingly for that release, Fantasia had undergone another restoration, of the “video paintbox” style that cleaned up many of the Disney classics for release in the 1990s. The intention for The Fantasia Anthology was to restore the complete, uncut road show edition of the film as it was originally conceived, though a problem was that although additional Deems Taylor footage was found and included, audio tracks remained undiscovered. The answer, or so it was deemed acceptable in 2000, was to re-record Taylor’s dialogue with an impersonator (regular Disney vocalist Corey Burton, if I recall correctly).

Burton’s a vocal chameleon and a great talent to be sure, but he ain’t Deems Taylor, and with that original dialogue and its wonderful 1940s intonations burned into my head, it’s like listing to the impostor that he, ultimately, is. It’s a problem that’s been carried over to Fantasia’s debut on Blu-ray, and though this new edition – coupled with its 2000 sequel – doesn’t exactly present itself “uncut” as before (because even then, the black centaur was missing), it does serve itself up as “The Original Classic”, which isn’t quite true either. What is true is that this Fantasia presents as close as possibly the original road show intent, without the main titles that now sit as they originally did in the middle of the film (though only for a few seconds, not the full fifteen minutes!), and the original intermission scenes restored (even more so than the 2000 release).

At the end of the film, Fantasia simply ends, without any end credits, and while that would have been fine in a road show engagement where audiences were given theatrical-style brochures that offered this information, it’s otherwise nowhere to be found here. When Fantasia was announced for Blu-ray release, it was as a deluxe collection that was to include a wealth of additional material: the holy grail, if you will, of old and new archive footage that would provide the definitive compilation of everything Fantasia, including the short films that were to make up a third edition of the film rumored for the mid-2000s.

One of these shorts, Destino, was a film originally conceived by Walt and famed artist Salvador Dalí in the 1940s, but abandoned after further Fantasias were not going to happen. Numerous pieces of artwork were produced by Dalí for the short, which the Disney Studio owned as long as the film was completed. Laying in the Disney vault for 60 years and discovered only while researching discarded concepts for other Fantasias in the making of the 2000 continuation, Roy Disney realized that the Studio could forfeit its right to the artworks unless the film was completed. Work was set in motion on finishing Destino, which would be featured in the next Fantasia, which was to have a world music theme.

Eventually, Destino was released in 2003 and was Oscar nominated, but the proposed third musical concert feature would not appear. Many hoped that the Fantasia World material announced for this set would be this quasi-third film, and when this collection was delayed from an early 2010 release to the end of the year, the rumor was that it was being re-worked in the wake of Roy Disney’s untimely death just a few months earlier. Well, the set does seem to have been reworked: but certainly NOT for the good!

I make no apologies for liking the 1990 anniversary edition of Fantasia. I think it works perfectly as a film in one sitting, and I very much liked the addition of the immaculate end credits placed against the musicians as they retire their instruments and prepare to leave. It’s true that the film was still censored, but more than anything, I like that we see and hear Deems Taylor, authentically from 1940. With the magic of Blu-ray, would it have been so hard to present both versions; the 50th anniversary “restored” edition and this 70th anniversary “complete” edition that was honest with the caveat that we wouldn’t be hearing Taylor’s original authentic voice, but at least we had the alternate version as an option?

Added to that, would it have been so hard for this collection to actually present the film uncut to the many adult fans who are no doubt the target audience for the film in hi-def? Or again offer an alternate version that plays the film uncensored, or at least includes the offending musical segment (Beethoven’s Pastoral) as a supplement, with a disclaimer if need be? Because, really, this is a wonderful visual restoration that makes Fantasia look and – in the symphonic music – sound better than ever before, but with both facets derailed by the faux Taylor’s voice and a couple of papered over scenes. It’s not that I’m bemoaning the removal of 15 seconds of material when there’s a good ten minutes been put back in, it’s just that it’s been done so badly!

One shot, of a centaur having her hooves manicured by the black centaur, named Sunflower if memory serves, has been zoomed in, and actually would go undiscovered by most if you didn’t know what was there before. The trouble is that Sunflower is obviously a black stereotype of the era, drawn unfairly with over-characteristically buck teeth and braids, and the demeanor that suggests she is happy to serve the beautiful (white) centaur getting ready to entertain the visiting menfolk. It’s obviously racist, and was so back then in those less sensitive times, but the way a second cut occurs actually looks as if there’s been a mistake, with two shots repeated so as to cover up the shot where the black centaur follows her companion, holding up her trail behind her.

Actually watching the same cover-up shot play twice right next to each other brings more attention to the moment than probably just letting it play, or again just zooming in to remove Sunflower from the shot. And, again, I have to say it, but the road show edition of Fantasia is a historical relic that really doesn’t work in a home showing. I’d have much preferred to see the stand-alone version, a complete film with authentic Deems Taylor in its own right, with the fully-intact road show version as an alternate “reconstruction” of the 1940 presentation, “for historical purposes” that could have included everything uncut and wouldn’t have “offended” so much.

Right…rant (almost) over. As a film, Fantasia is of course untouchable. Whether one can enjoy it or not – and even if many don’t enjoy it as a whole there’s still at least a couple of segments that they warm to – the sense that this is an important film, animated or otherwise, is clear. There’s a real sense of occasion to Fantasia, something that was effortlessly carried over to its sequel film in 2000. I remember going to see that in the Imax theater, and the combination of the multi-track sound and the huge screen gave me some indication of what it must have been like to be in the audience in 1940 when Walt’s original filled the auditorium with sights and sounds never before seen on a movie screen.

In an attempt to cut this review a little shorter (yes, I know…too late!), there’s plenty that could be said about Fantasia, but those comments, at least from me, would be best suited to the earlier, more rounded restoration. I can’t say that, as a release for the home, that Fantasia works as well as it should and can do, the road show presentation distances itself from the audience somewhat, with a bit of a stuffy atmosphere. For the first time ever, I can actually appreciate what the critics of the time were suggesting when they said Walt was going high brow, and that’s actually an awful thought!

Yes, the terrific animation is still here, from Art Babbit’s super-cute dancing mushrooms and the stunning beginning of life on Earth, to the aforementioned centaurs of the Pastoral (actually my favorite piece of music, played to me from before I was even born!), ballet dancing hippos and crocodiles and, of course, Mickey working his magic, all topped off by the tremendous clash of evil and good in the double Night On Bald Mountain/Ave Maria conclusion. It’s a striking venture that has been so debated and admired by so many people over so many years, that my humble comments could never do the film justice. It certainly divides opinion, but it never fails to elicit one!

That Fantasia 2000 can stand proudly alongside the original film 60 years later says all that it needs to say. Only the second official sequel to an original Disney feature, though only the first to follow on from a bona fide classic from Walt’s Golden Age of the late 1930s and early 1940s, the film was an attempt by the 1990s regime to state that they had come a long way from the likes of The Black Cauldron and were now more than capable of matching work from the best of Disney’s great artists. It was also the pet project of Roy Disney, perhaps with his own axe to grind in proving himself worthy of the family name, and how better to do that than stamp his imprint on his Uncle’s most personal project?

As a result, Fantasia 2000 works just as well as art as it does entertainment. The original concept was to pick up Walt’s vision, to present Fantasia again but with certain segments removed and new ones inserted. I understand why, as a valuable slice of branding if nothing else, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice was retained, but in many ways I wish it had been retired so that Donald Duck could take center stage this time, as he almost does with Pomp And Circumstance. It would seem to make sense to me to have Mickey be the face of the first film, Donald as the second and so on, but the Duck has to share the poster with his old adversary.

Other segments were originally going to make the cut, Fantasia 2000 intended to again run around two hours, with The Dance Of The Hours and The Nutcracker Suite undergoing extensive restorations to bring them up to Imax size screen quality. In the end, it seems modern audiences were just as prone as their 1940s counterparts to reject the length of the film, and these two segments were dropped shortly before release. But I’ve also never worked out why, if the intention was to pay tribute to the original Fantasia but offer things never seen before, why the 1996 restoration of Clair de Lune wasn’t held back or even included in Fantasia 2000. How touching that would have been.

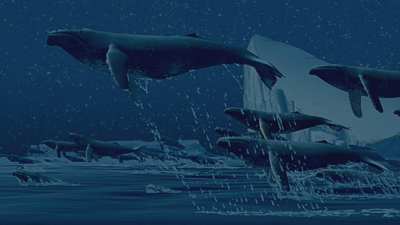

As for what is new, well considering that much of the film was produced in the early 1990s, one does have to marvel at that work: Roy Disney’s personal choice of Pines Of Rome (the flying whales) is a stunning highpoint, as is The Steadfast Tin Soldier, both pieces rendered in gorgeous CGI and completed before Toy Story hit screens: why Disney has been so slow to pick up authentic CGI animation acting until the current Tangled is a mystery based on the wonderfully fluid movement seen here. Fantasia 2000 also resembles its predecessor in its opening and closing choices: both films beginning with an avant guard experimental abstract piece, and closing with analogies for death and revival.

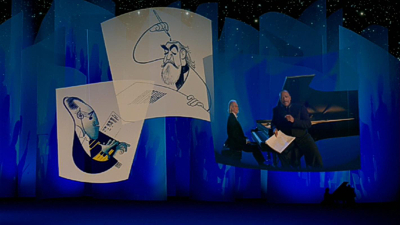

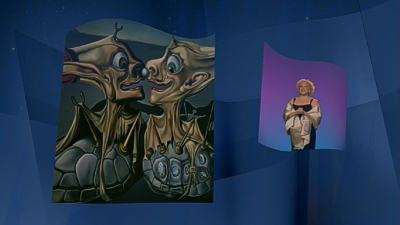

It’s funny, too: Eric Goldberg’s yo-yo flamingos in Carnival Of The Animals and Donald in his aforementioned segment, which takes on the story of Noah from the animals’ viewpoints, and the live-action interstitials (directed by Don Hahn) are terrific: replacing Deems Taylor after an excellent use of his original Fantasia opening, are a numerous list of appropriate faces from the worlds of music and entertainment, all of them suited and booted for the occasion. The production design is fitting, too, the concept being of artwork floating in the stars, coming to rest like sails (a tribute to sailor Roy Disney?) in an ethereal concert hall where the music rises to create the images. It’s all very delicate, perfectly reminiscent of the original film in its use of multiple shades of the color blue, and just so right and proper that whatever purists thought, they couldn’t argue that it wasn’t being done with the right intentions.

Ultimately, both Fantasias are very much part of the same world, and each film compliments the other remarkably well. Additional shorts were created for a potential third film, and its this that many were hoping for in the Fantasia World offering dropped from this hi-def debut release. There’s an absolutely FANTASTIC collectors’ edition of Fantasia to be compiled sometime, and it’s not to be underestimated that given the right ingredients, it could probably be the most landmark animation release of all time. The bottom line is: if you have that Fantasia Anthology collection, don’t ever let it go. If you don’t have it, beg, borrow or steal to get one, because this set ain’t it. Not by a long shot.

Is This Thing Loaded?

In short: not nearly as much as was hoped, with several quality issues to contend with and what is undoubtedly Disney’s most rotten home video decision ever…

I’ve already labored the point on how I’d have liked to have seen the original Fantasia presented: in its “general release version” restored in 1990, as an “alternate road show reconstruction” (basically the version we get here), and why not also throw in the 1982 edition, which was completely different again, removing Deems Taylor and replacing him with spoken narration. All three are valid interpretations of the original film, but this collection just isn’t interested in being anywhere as definitive as it could or should be.

With no less than four discs in the box, you might be expecting an enormous amount of supplements, but two of those discs are regular DVDs that repeat both films and just three extras (indicated below by an * asterisk mark). It seems rather crass in the Sneak Peeks that the likes of A Christmas Carol, Cars 2 and Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 should be promoted on a title that represents what Fantasia was meant to be all about, but that’s Disney’s magical synergy coming into play: other titles getting seen in Blu-ray 3D and preview spots include Bambi, Alice In Wonderland and The Incredibles among a couple of others.

The good stuff – what there is of it – is to be found on the Blu-ray Discs, with identical menus between both discs that replicate the production design for Fantasia 2000 though work just as well for the first film. Being an Academy framed 1.37:1 ratio feature, the black borders left and right of a 16:9 screen can be filled with Studio artist Harrison Ellenshaw’s DisneyView art panels, which strive to broaden the image. While Ellenshaw’s art is delicate and at times complimentary, it’s often also unintentionally distracting or contrasting in color. It’s better when abstract and muted in color, such as during the Pastoral, but in The Dance Of The Hours, the rigid vertical columns fight with the camera movement and feel claustrophobic. I’ve not found these Views much benefit in the past, and there’s otherwise no reason to start now!

Although absolutely fascinating to be invited in to see the finished building, the Disney Family Museum* (4:05) is more a promo piece for the recently opened institution based in San Francisco’s Presidio that caters to remember Walt the human being. Obviously Walt’s work is a large part of the Museum, and Fantasia was very personal to him, but I got the feeling that this item might have been better placed (or at least included in addition) to the concurrent Walt & El Grupo documentary. That said, it’s wonderful to be able to take a peek inside this terrific establishment, and I can’t want to someday make a personal visit.

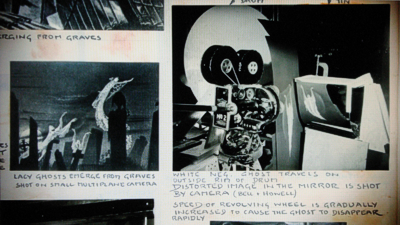

Much promoted as this release’s big new extra, The Schultheis Notebook: A Disney Treasure (13:50), and the connection to the introduction to the Family Museum immediately becomes more apparent when Diane Disney Miller presents us with a look at Herman Schultheis’ personal observations and annotations made during Fantasia’s production (another book glimpsed, entitled Future Fantasias, suggests Gershwin’s Rhapsody In Blue, which of course would wind up in the 2000 continuation). Described as “the Rosetta Stone of special effects animation”, the notebook contains the solutions to various problems faced by the effects department during the late 1930s and early 1940s. Such a marvel of intricate information and revealing photographic evidence of how some trick shots were achieved would be quite a feat to bring to the screen and so perhaps the slight disappointment is that we don’t get a chance to basically read the pages.

But as a montage of close-ups and narration (from historians John Canemaker, JB Kaufman and Charles Solomon among others) that glosses and glides over the book, it works well enough. There’s also a welcome brief history of Schultheis himself, who sounds as if he is nothing short of an unheralded replacement for Ub Iwerks after Walt’s original right hand man left the Studio to pursue his own work. Certainly it’s clear that without Schultheis, Fantasia wouldn’t have contained nearly half the amazing composites and mattes that make the film what it is, and some of the reveals here are frankly absolutely extraordinary to say the least, but the fuss over this feature in the publicity hides the fact that, in order to actually see the book, one has to visit the Museum at The Presidio!

An elaborate Interactive Art Gallery provides an over fussy way to peruse a wealth of concept and development art for both Fantasia and Fantasia 2000. The simple way to go is to look through both films’ art via the individual segment listing, but a complicated Smart Index provides an A-to-Z listing of subjects (selecting “umbrella” will bring up all images that have an umbrella in them) that one can easily get lost in. Thankfully, selecting an image brings it up almost fullscreen, though there’s a variety of ways to view them: in a Flow mode that rotates them along, or a multi-screen that kind of presents them like the galleries we’re used to. I could do without the ability to “rate” and “save” my favorites (fancy having to “rate” Fantasia art!), and if you think it’s annoying that those icons cover up the bottom of the images in fullscreen mode, know that you can press the down key to remove them. There are literally hundreds if not thousands of drawings here, just presented in a needlessly overwrought fashion until one gets the hang of it!

Lastly – yes, lastly! – we are presented with three Audio Commentaries, two of which have been pulled over from the previous DVD release. The first of those is the excellent archival track featuring Walt himself, pieced together from vintage recordings and hosted by John Canemaker, while the second gathers the creators of Fantasia 2000 (Roy Disney, conductor James Levine, Canemaker again and the film’s 1990s restoration supervisor Scott MacQueen) to speak about their views on the original film and how it shaped their continuation, while MacQueen discusses the challenges of restoration, now somewhat superseded by the digital scrubbing provided here.

Brand new to this release is the solo informational track* by British Disney historian Brian Sibley, known for his knowledge of animation and music and an excellent BBC radio host of several programs on movie music and history. He’s typically done his homework and come well prepared, with his radio background essentially providing a basis for him to perfectly execute a two hour audio documentary on the making of Fantasia. Where possible, he’s scene specific and there’s hardly an instance of dead space. The other two tracks are good, but we’ve heard them before: this repeats some oft-told information but offers other new insights and, as the only substantial supplement here, is the best the disc has to offer.

Fantasia 2000 doesn’t actually fare much better: redundantly the same Sneak Peeks are repeated, but at least the two DVD Audio Commentaries of old are retained from the Anthology set, with Roy Disney, James Levine and producer Don Ernst on the first discussion, and the directors and art directors of each segment on the second. Both tracks are worth a listen if you’ve not partaken before, but chances are you have, and so there’s nothing new to hear here.

The only other new feature is a Musicana featurette* (9:20) that takes a look at Mel Shaw and Woolie Reitherman’s ideas and concepts for a 1970s concert feature that may have been viable back then based on Fantasia finally making some money in the late 1960s. There’s a brief discussion (by Didier Ghez) on the Future Fantasias book that outlined idea for “sequels and/or replacements”, in which possibly the basis of the musical Package Features of the 1940s were formed (a heading reads “Outline for a popular – low cost musical feature-length film for general release”, which suggests more the “pop-Fantasia” approach of those films). Flight Of The Bumble Bee for instance, at one point developed for Fantasia, became the boogie-woogie Bumble Boogie in Melody Time. The idea of such musical films, or at least shorts sequences that could be compiled, was always in the back of the minds of the artists.

Actually, there’s a lot in Shaw’s work that suggests the film might have been a worthy endeavor, the world music approach sounding much like what the planned but discarded third Fantasia might have been like, and there’s also a jazz section that could have inspired the American South setting of The Princess And The Frog. As well as possibly including another favorite piece of mine, the Scheherazade Suite, It’s all pretty remarkable, actually, and one has to wonder in which direction Disney Animation might have ended up had this film been made, with the new generation of artists (John Lasseter co-developed the intended Mickey story The Emperor And The Nightingale) maybe taking it on instead of The Fox And The Hound or The Black Cauldron. Oooh, what could have been!

Perhaps the largest reason for the anticipation of this set is – finally – the release of the 2003 completed short Destino, originally developed by as an inclusion for another South American picture in 1946, but ultimately shelved until Roy Disney instigated the completion of the film for inclusion in the then-intended third Fantasia. I’d actually been lucky enough to see Destino back in 2006 during its screenings as part of the Once Upon A Time…Walt Disney inspirational art exhibition in Paris, and so the wow factor for me this time out was a little more dimmed than the excitement I felt seeing it for the first time. The originally proposed film was intended to bring Walt Disney together with a “real” artist, in this case Salvador Dalí, who around that time was enjoying something of a Hollywood love affair. Perhaps mindful of the critics that had savaged Fantasia as low art at best, Walt certainly wanted to continue pursuing the use of animation as a true art form.

The features of the 1940s went some way towards that, though their popular slant was a way for Disney to appeal commercially to general audiences who had likewise found Fantasia too high brow, and Walt was obviously itching to get more “serious”. On the other side of Hollywood, the celebrated surrealist Dalí was working with Alfred Hitchcock, himself a self-professed Disney fan, on the dream sequence for the director’s Spellbound. Walt heard that the Spaniard was in town, and they eventually met at a dinner party hosted by Jack Warner. Dalí, who on seeing Snow White had proclaimed Disney as “one of the three great American surrealists” alongside the Marx Brothers and Cecil B. DeMille, leapt at the chance of collaborating on their own film.

Dalí spent the next few months at the Studio, and by all reports the two artists got on fine. Destino was originally conceived as an eight-minute short, to be a combination of live-action and animation, but after numerous concept drawings and more than a couple of dozen completed paintings, the project – for reasons unknown – fell through. It wouldn’t be the first or last time Walt would abandon a fairly well developed idea around this time: a similar team-up with Aldous Huxley on another Alice In Wonderland never came to fruition, and a joint-effort between the Studio and British author Roald Dahl resulted in the publishing of a book but not the intended project that sparked the relationship, to be a feature film based on Dahl’s story The Gremlins.

Alas, Destino fell by the wayside after an 18 second piece of test footage was completed, and was abandoned after eight months of continued work. Walt moved his attentions on to the greater interests of live-action, special effects filmmaking and, of course, “living” cartoons in the genesis of his theme park aspirations, possibly mindful that he had reached the zenith of what could be feasibly achieved with animation artistically, at least in the direction he had taken it. Reconstructing the film with one of its original artists, John Hench, and director Dominique Monfery, using the original recording of the title song, a Mexican ballad by Armando Domínquez, for authenticity, Disney’s Paris studio was selected for the animation due to the film’s origins, and work began in May 2001 (a nice touch has the closing credits in dual English and French).

On release and with an eventual Oscar nomination, some criticised the film for being nothing more than a way for corporate Disney to finally gain ownership of the Dalí artwork – it was well known that the Studio Archive possessed the imagery but did not own the right to present it until Destino was completed one way or another, such was the contract signed between Dalí and Walt in the 1940s. However, one would like to think that it was an honest and artistically driven initiative, spearheaded by Roy after the title was name-checked in his 2000 continuation of Fantasia. This is the story told in the long-awaited feature documentary Dalí & Disney: A Date With Destino that, at over 82 minutes, is longer than the disc’s main feature by seven minutes and provides extensive background on the genesis of the original film and follows it through production to completion.

Dalí & Disney does present a very interesting story, and it certainly sheds light on what has always been an enticing yet strangely never publicised period in Dalí’s life (along with Jackson Pollack, the “limp watches guy” as he is amusingly described by Bette Midler in Fantasia 2000 has always been a favorite artist of mine, yet books and even films on his Hollywood days rarely even mention more than an “aborted project with Walt Disney”, if that). As a way to pad out the running time, there’s a lot of biographical information on both artists that consumes the first third of the documentary, played out in a chronological parallel. Thankfully the emphasis here is slightly more on Dalí instead of Disney, allowing fans to find out more about Walt’s collaborator rather than sit through an elongated Disney history once more, but biographer Neal Gabler does step again over much trodden ground even if it’s great to see Mike Barrier also acknowledged as an authority.

In addition, there are numerous attempts to suggest connections between Disney and Dalí’s work from before they met, and while there are similarities, some of these comparisons feel a little desperate at a stretch. Also, in an attempt to make what could be a very long and laborious exploration of art accessible to wider audiences, Dalí & Disney reverts a few times to newly made but flippant “newsreel” clips, which I didn’t very much care for, while the rest of the film’s very sombre detailing of the delicate nature of Destino’s production should appeal much more to admirers but will probably put general audiences off. But there’s a good discussion about the many layers of underlying meaning in Dalí and John Hench’s development artwork, and the stories behind them, which is truly captivating if you appreciate this sort of thing, and there’s no denying that the longer length allows for a great deal of depth…in certain instances.

However, there’s actually very little on Dalí and Disney’s original moves to make Destino – just over ten minutes out of the entire length – and even the focus on the completion of the film in the 2000s only fills the final third of this documentary. There’s a feeling, to me at least that, with Roy Disney’s passing late last year, the Studio had a need to put this material out without further delay and before the interviews started to date any more than they already have. As such, the bundling of Destino and this documentary into a fairly unconnected release of Fantasia feels like a very convenient “dumping ground” rather than the consummate feature-length documentaries concurrently issued on DVD about the Disney Studios (Walt & El Grupo, The Boys and Waking Sleeping Beauty). Dalí & Disney is very much a DVD bonus feature, but it is a significant and very refined one, and seems to me that it is deserving of more.

Quite what Walt or Dalí would have actually made of the completed Destino short has to go unanswered, of course, since their original intention was never realized. What Monfery and the creators (Hench is given co-writer status) of this short have managed to do, however, is to compose a definitive story through amazing abstract and surrealistic imagery. Set to Domínquez’ ballad (with English lyrics by studio writer Ray Gilbert, and performed by Dora Luz), the short doesn’t sit still for a moment, and despite its artistic aspirations, never feels simply like a bundle of paintings come to life. It’s experimental to say the least, but of the kind of mainstream experimentalism a big studio can afford to do every now and then. Heaven knows what the critics of the time would have thought – coming off the back of the derided Fantasia could have struck a bitter blow to Walt. But, now, we can marvel at this historic achievement – just three years shy of being 60 years in the making.

The style is all Dalí, the fairy tale love story (ostensibly about a ballerina who falls for a baseball player and their attempts to convene) all Disney. The movement is exceptional, the result of the CAPS system aiding the animators to create absorbing humans with real, human-like characteristics, but the CGI doesn’t blend as well as it might. Perhaps Dalí’s visual scapes – the Tower Of Bable, the monastery bell tower, the wall where the sands of time slip away, a nightmarish beach and, of course, the trademark eyeballs and melting clocks – are already too rounded and rubbery to be pulled out and about into strange proportions through the CG manipulations. But the Multiplane-styled effects work wonderfully, and ultimately Destino works, almost brilliantly, and, technology aside, it does feel like an old Walt short, principally due to the 1940s audio recording, which really assists in setting it in the period it might originally have been completed. Who knows…if Fantasia had been the artistic and commercial success Walt had envisioned, we might have seen Destino much, much earlier.

Although the finished film reflects the tone and style of Dalí’s flamboyant approach to art, it’s clear from his original images that he had a far more intricate and very different film in mind – his ballerina, for instance, is much more a classic Disney type here than the modern Esmeralda who dances through the 2003 Destino. Certainly examining the images at the exhibition in Paris a few years ago invited another viewing of the short, upon where many new details can be picked out, but unfortunately the inclusion of the film and the accompanying documentary doesn’t stretch to doing justice to Dalí’s original 17 pieces of artwork or any of the concept drawings by including them in their own dedicated stills gallery, yet another example of this release just not having its heart in the right place; the suspect quality of the documentary and the short explained further below.

But the worst is still to come and, lastly, shudder and be very afraid: Disney’s Virtual Vault is as bad as it sounds. I’ve been bemoaning the lack of real bonus features on this release, but whaddayaknow – they’re all right here…well, sort of, but if you don’t have your Blu-ray connected up to the internet, then, not at all. For quite a few of the original Anthology programs have been stored online, ready to be selected via this disc. Video – anything from two 50 minute documentaries to theatrical trailers – is buffered and played in a quarter screen window, skipping and stuttering as the video catches itself, re-buffering as the connection may lag, and struggling with interlaced fields.

Of course, there’s no way to increase this size or navigate forwards or backwards throughout this footage, but then the quality is so crummy I don’t think I’d want to. Worse still, what if in the future Disney decides to pull this material offline? It’s all well and good making some of those previous features available via a Virtual Vault, but then don’t make people pay out for a full-featured, near $50 set when it’s anything but! In terms of technical quality, viewing convenience and buyer’s value, this is frankly the poorest decision Disney Home Video has ever made, and a real shambles on a title as important as this. In short: it’s cheap, it’s nasty, it’s crap, crap, CRAP!

In fact, the sheer sparseness of any substantial new supplements on these discs is so astonishing that I actually spent around five minutes trying to find a missing link to a further stash of extras on both the Blu-rays. I just can’t believe that with the historic standing of the original film and its not undistinguished sequel, the Fantasia films haven’t been treated better than this on Blu-ray. What the set amounts to is nothing more than a hi-def upgrade for those with the original Anthology set…fine for those with that collection, but little use in terms of background context for those coming to the films anew or wanting HD upgrades of some of those extras. A better set must surely be in the offering at some point down the line, but in the meantime, if this is supposed to be how Roy Disney is to be remembered by the company, it’s a very underwhelming tribute.

Case Study:

Pretty much about as basic as a Blu-ray special edition can get. The awful front cover title treatment, which instead of the much better Fantasia: 2 Movie Collection design, repeats both titles, is otherwise quite nice and representative of both films, with star of both Mickey riding high as The Sorcerer’s Apprentice surrounded by only a few of the supporting characters, including Donald. The embossed shiny slipcover makes great play of the inclusion of Destino both on a front cover sticker and it’s own promo spot on the back, though I do very much enjoy the old image of Mickey shaking hands with Stokowski now augmented by having Donald tugging on his tails – nice!

The disc art does what the films should have done and have Mickey for the original and Donald on the second, while the DVDs are as dull and gray as the almost non-existent extras they hold. There’s a Movie Rewards code and a booklet that promotes top-line Fantasia keepsakes as well as the recent awful disgrace to the company’s heritage, this past summer’s live-action Sorcerer’s Apprentice movie, the less said about the better.

Ink And Paint:

Ouch! You can pretty much guess that any comments toward a full digital restoration for Fantasia are going to border on the phenomenal, even if I found the overall color palette to be a little lighter than I have seen in the past: the result of brightening or just the clarity of Blu-ray? Fantasia 2000 looks as good as a digitally produced film should do, but whatever has happened to Destino!? For such a much heralded inclusion, I was expecting nothing less than digital perfection for this 2003 short, but here it is from a film print, with scratches, gate weave, exposure fluctuations and other artefacts that date it more in keeping with its 1946 inception! Worse still, the Destino documentary seems to have been upscaled from standard definition – just what the hell is going on with this release!?

Scratch Tracks:

Well, why stop now? While Fantasia’s musical selections sound quite wonderful in this new 7.1 enhanced mix, the separation isn’t as wide as you might expect for a track that apparently went back to the Fantasound stems. Added to this that we don’t get the option of hearing Deems Taylor’s original voice as an alternate track (what would be the harm in offering a track that only replaces Taylor’s dialogue where it was needed?) and there’s a still noticeable amount of signal noise in very quiet passages (which I can understand would be impossible to remove without harming the fidelity of the soundtrack). I just can’t get that excited about the sound on this release, which should but doesn’t sound as fresh and authentic as recent upgrades for Snow White or Pinocchio.

Fantasia 2000 naturally sounds like a brand new movie, because it is one, and the music literally sparkles out of the speakers with a great top end and a rumbling deep bass. If there’s one reason to own this set, it’s really to grab Fantasia 2000 looking and sounding as great as it does here. Destino, again on the other hand, is restricted to its source music, recorded in 1946, but actually this does the film a favor: although it doesn’t sound as sharp as a new recording, there’s a vintage essence that lends the short a dated authority, acting as the connection between its origins and completion almost 60 years later, but again I must wonder what has happened for the song to sound so distorted at some moments. English, French and Spanish subtitles and Enhanced Home Theater tracks are included, with Fantasia sounding, I thought, a little better off the 5.1 DVD.

Final Cut:

Really this release should be referred to as “A So-so Copy Of Destino: With A Chance To See Fantasia And Fantasia 2000 In Hi-Def”, since that’s basically what you get in this box. And that’s a shame because, although it’s fantastic to own the completed 2003 short film – despite the lower than expected quality – and the feature-length documentary that accompanies it, those were both slated to appear as part of Roy Disney’s Legacy Collection releases some three or four years ago and now they’ve been “dumped” out here in a quasi-release that feels unbalanced to say the least. In fact, apart from its intended inclusion in a never made third film, Destino has no connection to Fantasia anyway!

So…oh, what might have been! A first Blu-ray Disc dedicated to the three main editions of Fantasia to appear over the years. A second disc containing Fantasia 2000 and appropriate supplements to that release. A third disc presenting the vast amount of material gathered for the Fantasia Anthology bonus disc Fantasia Legacy – now with that material in hi-def – and a fourth disc presenting additional vintage material and Fantasia World, featuring the completed editions of Clair de Lune, Destino, Lorenzo, One By One, The Little Matchgirl and whatever the “never before seen animation” announced in the teaser was, along with the Dalí And Disney documentary (in true HD?).

Wow, this release could really have been something. As it is, we get a censored and non-original voiced first film, the second one, and a lot on Destino, but not enough, that should have been its own release. There’s value in here somewhere, not least in Fantasia 2000 in hi-def, which is a sight to see. Fantasia looks great too, but the road show edition is choppy and far from the ideal version of the film to present in one sitting. It’s certainly nice to have Destino, but it’s ultimately just a short film, and a fairly odd and obscure one at that, so whether the set is worth it for that or the generally bad quality of the short, documentary and total lack of durable extras is open to debate.

I just guess, at the end of the day and considering what this could have been, Fantasia greatly disappoints in its much heralded Blu-ray debut. Picture restoration aside, this collection surely won’t amaze-ya at all.

| ||

|