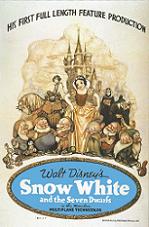

There are several origins to Walt Disney’s choice of Snow White as his very first animated feature.

There are several origins to Walt Disney’s choice of Snow White as his very first animated feature.

One of them is that it was the subject of the very first film he had ever watched, as he was 14, in a theater with his fellow newsies in Kansas City, having won a ticket. It was a silent film projected on four screens at the same time through a new system, featuring Marguerite Clark in the title role.

Another one comes from Walt’s grandmother. As he remembered, “When I was a child, every evening after supper, my grandmother would take down from the shelf the well-worn volumes of Grimms’ fairy tales and Hans Christian Andersen. It was the best time of the day for me, and the stories and characters in them seemed quite as real as my schoolmates and our games. Of all the characters in the fairy tales, I loved Snow White best, and when I planned my first full-length cartoon, she inevitably was the heroine.”

So, this project was really his own, from beginning to end. In 1934, he gathered his lead animators in a little soundstage, and, during four hours, we told and played the whole story for them, even already envisioning the songs. For three years, the Walt Disney Studios were to make Walt’s folly come true, a huge project he would fully master. As David Tietyen wrote: “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was Walt’s personal masterpiece. Although Walt was involved in all of his studio’s productions, Snow White completely engrossed him. He developed the storyline continuity, described in minute detail what each scene would involved, suggested what lyrics should be used in songs, selected the songs to the used, cast the voices, and lived and breathed the film for the more than three years that is was in production.” – not bad for a 33-year-old!

Snow White heralded Walt Disney’s genius as a storyteller. But how much? We all know about the visual impressiveness of the film, but an animated movie is much more than just about visuals. It is also very much about music, and more especially about how music takes part in the movie – the visuals and the story. And Walt, from the very beginning, with Steamboat Willie, has always understood that…

The art of make-Believe

Visually and character-wise, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs combines all the innovations developed with the previous cartoons, and particularly the Silly Symphonies. For example, the Multiplane Camera, used in the With a Smile and a Song sequence was first experimented in The Old Mill (1937).

The same attention to believability can be found in the new effects conceived by the Effects Department that, during the production of Snow White, counted no less than 56 people. Hence the remarkable rendition of water (the ripples in the wishing well), of the rain or else the shadows, that become transparent thanks to a special painting. Scenes become more and more complex and demand for more and more precision because of an increasing number of characters to animate (the dwarfs, the animals, etc…), sometimes up to 40 in one shot. Hence a bigger format for the animation sheets and tables, and the conception of new photographic reduction processes.

The characters themselves become more realistic. If the Witch is obviously derived from Babe from Babes in the Woods (1932), the relative failure of The Goddess Of Spring in 1934 demanded for a new way of approaching and animating human characters, and young girls in particular. That’s how Walt came to appeal to Don Graham, teacher at the Chouinard Art Institute, in order to train his animators. Thanks to this class, Snow White was the first animated heroin to move with believability, grace and fluidity. Reference films were also used, with actors playing the scenes. That idea came out during the creation of Dopey. He seemed close to comedian Eddie Collins. So, the later was asked to be filmed and, in return, he was very inspirational to the creation of the character.

For Snow White, it is Marjorie Celeste Belcher (who was to become later the famous dancer Marge Champion, Art Babbit’s wife) who played her for the camera. She also inspired the character of the Blue Fairy (she shares the same upper face with Snow White) and would dance for reference for Fantasia‘s Dance of the Hours. These kind of reference films are still in use today. As for Snow White’s blusher, far more natural than cartoon human characters of the time, it is due to the young ladies of the Ink & Paint department: instead of paint, they used their own make-up, which gives the Princess’ cheek that delicate pink tone. Walt considered that technique was a true improvement, but felt concerned about the possibility to use it on each of the drawings. Then, one of the inker ladies said: “But Walt, what do you think we’ve done all our lives?”

Remember that at those times, realism was new. Animators would come from cartoon, from gag, from caricature. It was revolutionary to envision a full-length movie that would be fully animated and to create believable characters and scenery in order to do so. But the revolution was not only on the visual side. It was musical, too!

One (new) Song

In its way of using music, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs widely draws its inspiration from what had been experimented with the Silly Symphonies, too (for a while initially, the project was called Feature Symphony). But that idea was quickly abandoned to better create a kind of an animated musical, with dialogue and songs, all combined in a unique way. As Walt Disney said at the time, “Really, we should set a new pattern, a new way to use music – weave it into the story so somebody doesn’t just burst into song.” So, the whole movie is built on a musical rhythm, a musical pace and the songs are no pauses but are rather partaking of the story progression or of the character’s personality. With Walt Disney, music becomes more than an illustration. It’s a partner.

For instance, the musical romanticism devoted to the character of Snow White is definitely unheard of at the time and makes her all the more believable, all the more human and all the more “Princess”. But at the same time, she can be very plain, very popular: Whistle While You Work depicts housework and chores as positive things. And she’s also a model of optimism. Despite the Queen’s hatred, she keeps hoping (I’m Wishing). And the same after her terrifying escape through the forest (With a Smile and a Song).

The style of the songs allows to define the nature of the characters’ feelings without any relation to their social condition. For instance, the lyricism and romanticism of One Song corresponds to Snow White as a servant, and Some Day My Prince Will Come to her stay at the Dwarfs’ cottage. So, the songs depict the nobility of her feelings, not of her condition. And as for her spontaneous nature, it is presented to us through With A Smile and a Song and Whistle While you Work, written in a popular style, with a bass line and way of using the flutes and muted trumpets characteristic of jazz bands.

The songs also allow to represent the relationships between different characters. Thus, as soon as they appear on screen, the Dwarfs are connected to Snow White, both visually and musically. In that sequence, following Walt Disney’s very instructions, Snow White, at work at the cottage, fades out as we move to the mine to meet the Dwarfs, also working : “Change the words of the song so they fit in more with Snow White’s handing the animals brushes, etc… Snow White: ‘if you just hum a merry tune’ – and they start humming… Then Snow White would start to tell them to ‘whistle while you work’. She would start giving the animals things to do. By that time, she has sung, of course… Birds could come marching in. Try to arrange to stay with the birds for a section of the whistling… Get it in the woodwinds – like playing something instrumentally to sound like whistling… Get a way to finish the song that isn’t just an end. Work in a shot trucking out of the house. Truck back and show animals shaking rugs out of the windows – little characters outside beating beating things out in the yard. Truck out and let the melody of Whistle While You Work get quieter and quieter. Leave them all working – birds scrubbing clothes. The last thing you see as you truck away is little birds hanging clothes. Fade out on that and music would fade out – at the end all you would hear is the flute-before fading into the Dig, Dig song (Heigh-Ho) and the hammering rhythm.”

So, the cleaning of the house is presented symmetrically to the Dwarfs’ digging. Snow White’s musical universe (on its “plain” side) is directly connected to the Dwarfs’. Whistle While You Work and Heigh-Ho belong to the same popular style, with similar orchestrations and arrangements. Both songs promote the same kind of values, the positiveness of work, in other terms Victorian work ethic. And that’s all the clearer when reading the lyrics, published by Bourne in 1938, that differ somehow from the ones of the 1937 movie:

in our mine the whole day thru.

To dig dig dig dig dig dig dig

is what we like to do.

And while we dig we always sing,

for when you dig there ain’t a better thing

than a tune (than a tune),

you can whistle or can croon.

We dig dig dig dig dig dig dig

and we try to do our bit.

We dig dig dig dig dig dig dig

until it’s time to quit.

And we warble down the scale

as we all go marching down the trail

right along (right along),

to the rhythm of the song.

Heigh-ho, Heigh-ho

To make your troubles go,

jut keep on singing all day long,

Heigh-ho, Heigh-ho, Heigh-Ho

Heigh-ho, Heigh-ho

For if you’re feeling low

you positively can’t go wrong with a Heigh, Heigh-ho

Heigh-ho, Heigh-ho

It’s home from work we go.

Heigh-ho, Heigh-ho, Heigh-Ho

Heigh-ho, Heigh-ho

all seven in a row

with a Heigh, Heigh-Ho.”

So, song can create bond, even a relationship between the characters. Snow White and the Prince through Romanticism (One Song ; Some Day My Prince Will Come), and Snow White and the Dwarfs through simplicity. And that relationship can be stressed by the development of the themes of the songs throughout the score.

Actually, in animated films more than in any other kind of movie, the score and the song are intricately connected, all the more when they’re by the same musicians. The music of Snow White was Frank Churchill’s responsability. First, he had to compose and arrange the songs for the film that are to constitute the basis of the score. A native from San Luis Opispo, California, where his father had a ranch, he studied music at UCLA before becoming a pianist in Mexico, then for a radio in Los Angeles. Hence, probably, his skills as a melodist and taste for popular music, which allow him to join Disney in 1931, after the departure of Carl Stalling the previous year.

Churchill started composing songs and scores for many Silly Symphonies like Three Little Pigs (1933), Lullaby Land, The Grasshopper and the Ants (1934) and The Flying Mouse (1935). Along with lyricist Larry Morey, he wrote no less than 25 songs, among which Music In Your Soup, and You’re Never Too Old To Be Young, to which The Dwarfs’ Yodel Song was preferred. In the end, eight songs were selected for the film, among which Someday My Prince Will Come, that was soon to become a radio hit.

But Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is also the result of a fruitful collaboration, awarded by an Oscar nomination, between score composers Frank Churchill, Leigh Harline and Paul J. Smith. Three characters, three different personalities, three different talents that created together a new artform that benefited from a then-new medium. Indeed, their soundtrack was released in 1937 as a three LP set by Victor Records – and not re-recorded, as it used to be for a film soundtracks at the time. Disney had produced the very first original soundtrack, with original voices and sound effects, testifying how much united those elements are in the film!

On the contrary, no link between the songs and the score can also be most significant. For instance, the last main character of the story is the Evil Queen, who is to become the Witch, and she doesn’t sing. So, she’s naturally separated from the other human characters. Not only because she doesn’t sing, but also because of her musical style. It is composer Leigh Harline (Pinocchio‘s main composer and songwriter), who was in charge of the Queen’s underscore and all the dramatic moments (Magic Mirror, Transfiguration Music, Theme Sinister). His music operates a thrilling contrast regarding Frank Churchill’s straighter score, notably through references to classical music. Harline’s orchestration is rich and deep, with dark timbres created by the English horn and the clarinet playing above string tremolos reminiscent of Wagner’s operatic style. The Witch is an intruder in Snow White‘s visual AND musical universe.

Someday my “pace” will come…

With Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the use of music at the service of story became much more sophisticated than in cartoons, for a great impact on the audience in intensifying the drama, embodying the characters, moving the story forward and conveying all the values, the message of the movie. From his very first full-length feature, Walt Disney mastered the form at the highest level. As we’ve just seen, he knew how to weave a song within the narration. But he also showed an incredible mastery of the collaboration between musical vocabulary and cinematographic vocabulary, from the structural point of view. In brief, he perfectly knew how to pace his movie and make that pacing significant.

The film opens and closes with a relatively fast, sequential editing (every 1 to 3 minutes, in general), based on contrast (from the Queen to Snow White, or from inside the castle to the wishing well, for example). And you can all the more feel it as it also correspond to a (clever) change of composer. If Paul J. Smith is doing wonderfully in the escape sequence in the forest, the whole film is built mostly on an alternation between positive scenes scored by Frank Churchill and scenes with Queen (or the Witch) scored by Leigh Harline with a dark orchestration and a tormented harmony:

One Song (Churchill) / Dramatic Music (Smith) / Animal Friends (Churchill);

And in the end:

I’ve Been Tricked (Harline) / The Silly Song (Churchill);

Pleasant Dreams (Churchill) / A Special Sort of Death (Harline).

But, in the middle of the movie, there’s no more alternation. Rather homogeneity and continuity. If Leigh Harline’s music appears here and there, it is just for a few seconds and to match Frank Churchill joyous style, inspired by popular music. That special part of the movie begins at the second occurrence of Heigh-Ho and gathers Let’s See What’s Upstairs, There’s Trouble a-Brewin, It’s A Girl, Hooray! She Stays and The Washing Song. A continuous block of 20 minutes, that draws the attention because of its size and its homogeneity. Never is that long sequence fractured. The music plays continuously, both tender and fanciful, which gives a feeling of stability regarding the rest of the film that keeps skipping from one place to another, one ambiance to another.

How impressive is Walt Disney’s mastery on his film as the alternation of ambiances and composers makes us focus on that central segment that stands out because of that homogeneity (and makes the following scenes, with the Witch all the more dramatic because, thanks to it, we really care for Snow White and the Dwarfs). If Disney invites us to focus on that passage, it is certainly because it contains something important – essential – to the understanding of the point of view of the movie. It is about the valorization of a simple life. The Dwarfs are simple because they react as children, with their heart and not intellectually (Dopey is certainly the most characteristic of them, all the more since he is the only Dwarfs to have his own theme, Dopey’s Theme). They don’t calculate, like the Queen. Beside, that passage contains no tension: the Queen doesn’t know Snow White is still alive, so there is no threat. That stressless life is a country life, a rural life in which work is necessary (housework, work in the mine), work that is nice and offered (Heigh-Ho, connected to Whistle While You Work).

Make “mine” music

That process is not only about telling things, but about feeling things, feeling this absence of tension through the absence of rupture in the musical score. Walt Disney understood that music has the ability to change the rhythm of sequences, in order to make connections between them and focus on the most important ones. That central passage would have not be so relevant if it weren’t located between sequences built a completely different way.

That shows a fundamental aspect of music in Walt Disney, which makes his films stand out from the other studios’. Walt understood that music has its own way of telling stories, in synergy with the pictures, the visuals, the editing, etc. Walt Disney’s genius in the matter of music is to respect the specificity of the musical language and to know how to use it in collaboration with the visual storytelling, as a semantic partner to the movie. The only model he could refer to at the time was opera or operetta. Even musical theater composers didn’t realize that songs could actually tell stories until 1943 (with Oklahoma!) – before then, songs were just kind of a hiatus within the actual narration. So, Walt was certainly a precursor, on more than one account, be it in the field of cinema, but in the field of music in general. And he did all that in Snow White, in his very first full-length film.

Considering that, Paul Smith’s assertation can now be fully understood: “Occasionally you really fall in love with a film. In my case, it was Cinderella. Walt’s great love was Snow White“.