“Who Discovered Roger Rabbit?” – a big question indeed, which was being continually asked during the late 1990s, after the huge success of Who Framed Roger Rabbit in 1988 and the Roger Rabbit “Maroon Cartoons”, Tummy Trouble, Roller Coaster Rabbit and Trail Mix-Up. But this was no ordinary sequel that was being envisioned by the Disney Studios and Steven Spielberg’s Amblin, but rather a prequel.

“Who Discovered Roger Rabbit?” – a big question indeed, which was being continually asked during the late 1990s, after the huge success of Who Framed Roger Rabbit in 1988 and the Roger Rabbit “Maroon Cartoons”, Tummy Trouble, Roller Coaster Rabbit and Trail Mix-Up. But this was no ordinary sequel that was being envisioned by the Disney Studios and Steven Spielberg’s Amblin, but rather a prequel.

Originally entitled Roger Rabbit II: Toon Platoon, the script, involving Nazi spies infiltrating Hollywood (and especially radio, where Jessica was working) was soon reworked, following Steven Spielberg’s wishes not to feature Nazis in his films anymore after Schindler’s List. And so the film became Who Discovered Roger Rabbit?, taking place during the Great Depression and a musical comedy environment, and now supervised by legendary animator Eric Goldberg (Aladdin‘s Genie). That’s where composer Alan Menken and lyricist Glenn Slater [both right] enter. Five songs were planned, with Menken proposing to be both a songwriter and an executive producer on the film. Roger’s return to the screen was off to a promising start, yet the right elements failed to gel at the right time and the project was unfortunately soon abandoned, the traces of its development scarce to come by ever since…

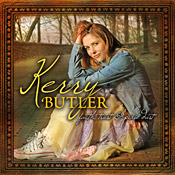

…Until today, as Broadway sensation Kerry Butler (Little Shop of Horrors, Beauty and the Beast, both by Alan Menken, and Xanadu) decided to record Faith, Trust and Pixie Dust, an album of Disney songs, along with her producer, Michael Kosarin (Menken’s conductor and arranger) and orchestrator Michael Starobin (The Hunchback of Notre Dame), and that would include never-produced-before Disney songs, such as Aladdin‘s deleted Call Me a Princess and… Who Discovered Roger Rabbit?‘s This Only Happens in the Movies!

A stylish, elegant and at the same time funny collection of songs, remarkably arranged and sung, the album’s release gives us the perfect occasion to discover this true rarity, about which Alan Menken’s lyricist partner Glenn Slater (The Little Mermaid Broadway Musical, Home on the Range) kindly accepted to talk about with us.

So, you see, this not only happens in the movies!

Animated Views: When did you start working on Who Discovered Roger Rabbit?

Animated Views: When did you start working on Who Discovered Roger Rabbit?

Glenn Slater: If I remember correctly, it was the summer of 1998. Alan had begun working on it with another lyricist (Richard Maltby, if I recall correctly), and for some reason it wasn’t quite working out to everyone’s satisfaction. Alan’s manager, the late Scott Shukat, had just taken me on as a client and suggested to Alan that (even though he had never heard of me, and despite the fact that I had almost no professional credits at all) I might be a good fit for the project. We met and worked on a few songs for the project, and (thankfully!) clicked.

AV: From what material did you work?

GS: We worked from a story outline, in parallel with the writers who were working on the script. As we began developing score, they began developing the dialog, and we worked quite closely to get the two to work together.

AV: What was the story like at that time?

GS: The film, called at the time Who Discovered Roger Rabbit?, was meant to be a prequel to the first film, telling the story of how Roger came to Hollywood and became a star. In the way that the first film was a spoof of film noir, the prequel was meant to be spoof of RKO and MGM musicals of the 30s and 40s.

The story involved Roger and a human friend; as the story begins, they are working the vaudeville circuit as partners, doing a magician-and-his-rabbit routine. They decide to follow their fortunes to Hollywood; through a series of misadventures, Roger (the “untalented” partner) gets noticed for his accidental slapstick skills, and does indeed become a star, winning the love of child-star-turned-adult-knockout Jessica along the way.

AV: Did you see any artwork?

GS: I don’t think the artwork got past the rudimentary screen-test level; if it did, I didn’t see it.

AV: Can you tell me about the song This Only Happens in the Movies featured in Kerry Butler’s latest album?

AV: Can you tell me about the song This Only Happens in the Movies featured in Kerry Butler’s latest album?

GS: This Only Happens in the Movies was written for one of the early scenes in the film. Roger and his friend have just arrived in Hollywood, and have been hired as waiters at a grand party thrown by the town’s biggest producer, to celebrate his new movie musical, starring a celebrated Fred Astaire/Ginger Rogers-type dancing duo. After toasting the stars of the film, the producer asks them to perform one of their famous numbers, called This Only Happens in the Movies. The male half of the team, a nasty drunk, is too incapacitated to perform; but Roger’s friend, who has had a longtime crush on the female star, steps forward and says that, having seen every one of the teams previous films dozens of times, he has memorized the entire routine and can step in for the star. The female half of the team is skeptical, but the crowd insists. They begin to perform the number, dutifully singing the words to the old song; but Roger’s friend is truly good – better than the star himself – and as they sing the words, about the kind of moments that are so perfect they can only happen in movies, they begin to have one of those moments themselves. By the end of the song, they have begun to live the song, and have fallen in love “at first sight”, just like in a corny old Hollywood musical. And as the song ends, as they gaze into each other’s eyes and the crowd holds its breath, of course Roger destroys the moment by accidentally causing a catastrophe of broken dishes, flying cutlery and general mayhem. The idea was to create a shimmeringly beautiful moment for Roger to utterly and completely ruin, so the song needed to be, in a sense, the very opposite of what you would associate with Roger Rabbit.

AV: The song offers several levels of reading.

GS: We were trying to create a song-within-a-movie-within-a-song-within-a-movie, with a layer of self-conscious irony built in. The idea was to write a song that is drippingly romantic in one context (the original movie it was supposedly performed in), yet can comment on itself ironically in a new context (the “real life” situation the characters are performing it in), and yet can, by virtue of the fact that that the characters know that they are “performing” a “number”, someone end up being more romantic than ever before.

AV: How did you work with Alan Menken on that song?

AV: How did you work with Alan Menken on that song?

GS: Alan and I were working on several songs simultaneously, trying to capture some of the different styles of the songwriters of that period – Gershwin, Cole Porter, and so on. We knew that we wanted the songs to feel completely of that era…but we also wanted them to have a smart twist that would let us wink a little at the era as well. I came to Alan’s studio one afternoon with a list of title possibilities and some scraps of lyric ideas, and this was one of them. I think I might have brought him the entire first verse, but that’s it. As Alan usually does, he sat down at the piano with the words in front of him, and the whole melody came reeling out in one swoop. And I broke out into a big grin and took the melody home in order to fill in the rest of the words, which I sent to him a few days later.

AV: How did you create the lyrics?

GS: In preparation for work on the film I delved into the lyrics of Ira Gershwin, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, all the old Tin Pan Alley greats, and tried to get a feel for the type of language they used, the kind of imagery they evoked, the feel of popular lingo of the time. In this particular song, I wanted to make it feel “authentically” like an old song from an RKO Astaire film, so I tried to capture the slightly-stilted feeling you might hear in an old Jerome Kern song, with a verse that had the insouciant field of, say, a Dorothy Fields lyric. And to make sure that the gorgeous melody would really “sing”, I tried to use as many open vowels as possible.

AV: Can you tell me about the other songs you wrote for the film?

GS: We wrote a song for Jessica called Good Little Girl. In the script, Jessica is a former child star, with a stage mother who insists that she keep singing her old songs and wearing her old costumes. Needless to say, the old costumes fit rather differently now that Jessica has, uh, blossomed into womanhood. And the old songs, which would have sounded very innocent coming from a young girl, now have a very different effect. Good Little Girl is a sort of a Shirley Temple-ish number, bouncy and prim, with lyrics that are one double-entendre after another. Jessica is aware that the song is completely inappropriate, and embarrassed at having to perform it, so this is another multi-layered number – an innocent song in one context, made salacious in another context, made sort of heartbreaking by its placement in the movie, since we can see how uncomfortable it makes Jessica.

There was another song, called Things Like Us Don’t Happen Every Day, that we made a demo for, but I don’t remember how it fit into the film. And then there were a few half-finished numbers.

AV: What was the musical approach to the movie?

GS: Most definitely, it was approached like a musical.

AV: Why was it never achieved?

GS: If I remember correctly, it simply proved impossible to bring the film in under a realistic budget.

AV: How do you feel about hearing your song at last produced on Kerry Butler’s album?

GS: It’s one of the first – if not the first – song that I wrote with Alan, so I’m thrilled it is finally going to have chance to be heard. Hearing it framed and given life by Michael Starobin’s fantastic new orchestrations has been a huge treat. And of course, having the song introduced to the world by Kerry Butler, whose gloriously warm voice makes everything sound good, and who perfectly captures the yearning shimmer of the words and the melody…well, that’s just the icing on the cake!

With all our gratitude to Glenn Slater and Tommy Krasker (PS Classics).