Just about anyone growing up speaking the English language likely was raised on the magnificent works of Dr. Seuss. In fact, you did not necessarily need to be speaking English, as his books have been translated into over 20 languages. I’m not sure how well his work actually translates, as much of the charm is in the rhymes and alliteration, but it is nice to know that so many have been exposed to the whimsy and imagination of Dr. Seuss. Aside from his admiring readers, countless others have enjoyed the various animated adaptations of his work. Most are familiar with his TV specials, of course, but I wonder… How many people know about the earliest collaborations that Dr. Seuss had with some of the brightest lights of the animation world?

What do you think the earliest Dr. Seuss cartoon was? How the Grinch Stole Christmas? Nope, you would be off by a few decades. This article will take a look at the contributions that Dr. Seuss made to the animation world well before his television specials. If you are just discovering your inner animation historian, you may be surprised to find out just whom the good doctor was hanging out with back in the days before television.

Who is Dr. Seuss? – A Primer

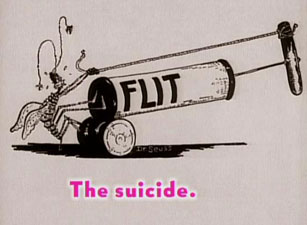

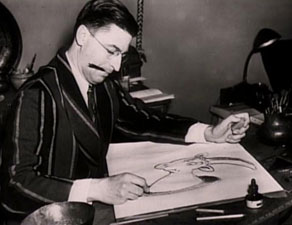

In order to place everything in proper perspective, we must first look at just who Dr. Seuss was. Any Seussophile knows that Dr. Seuss was actually Theodor Seuss Geisel (1904-1991). Born in Springfield, Massachusetts, he likely had many an opportunity to view and be inspired by a variety of creatures at the Forest Park Zoo, where his father was a curator. He attended Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., where he edited the school’s humor magazine. After graduating from Dartmouth in 1925, he started a Ph.D. in English literature at Oxford, but dropped out when he found it unfulfilling. Returning from Europe in 1927, he soon saw a cartoon of his published in The Saturday Evening Post and found himself on staff at the humor magazine Judge; he also submitted cartoons to other magazines. Some of his cartoons made reference to Flit, a mosquito repellent, which led to a career in advertising when the Flit manufacturer signed him up for an ad campaign. This association lasted seventeen years, during which he drew countless mosquitoes as fanciful but distasteful creatures. He also did advertising work for Esso and Ford, among others.

In 1935, Geisel worked on a comic strip for King Features Syndicate called Hejji. The strip featured the adventures of a young boy in the mythical Land of Baako. This may have been the first published use of the pen name “Dr. Seuss”, where he utilized his middle name and used the appellation “Dr.” to honor his father, who had wanted him to study medicine. He used the “Dr. Seuss” name in order to save his real name for more serious work. (Years later, he earned the appellation of “doctor” when he was given several honorary doctorates, including one from Princeton.) A great curiosity for Seuss and comic strip buffs, Hejji ceased publication by the end of 1935.

His decision to branch out into writing children’s books began with him being commissioned by a publisher to illustrate a collection of children’s sayings, called Boners. Not long after, he tried his first solo effort, To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street; but the book was not exactly welcomed by publishers. Thirty or forty of them rejected it before it saw publication in 1938. It was Vanguard Press (a division of Houghton Mifflin) that first published Seuss, for which generations of children can be thankful. His success may have been slow to come after writing his first book, but once he was published, he became amazingly popular. Four more of his books were published before World War II, and after the War he resumed his children’s book work with 1947’s McElligot’s Pool. Over his lifetime, he wrote over fifty books that sold millions of copies (over 200 million at the time of his death, and still counting!). His Green Eggs And Ham is one of the best-selling children’s books in the English language (fourth on the all-time children’s hardcovers list), despite the fact (or because of it) that it uses only fifty words.

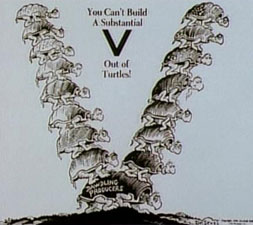

He had many other accomplishments, though. He was an editorial cartoonist for the New York paper PM from 1941 to 1943, contributing over 400 cartoons. He also did a number of cartoons for the War Bonds campaign, and these appeared in many papers during the War years.

At 38, he was too old to be drafted; so, wanting to make a larger contribution to the War effort, Geisel tried to hook up with Naval Intelligence. To his chagrin, he ended up being assigned to the Army during World War II and was sent to California to write for Frank Capra’s Signal Corps Unit. There, he received the Legion of Merit, and two of the films he worked on received Academy Awards. In 1945, he wrote and produced the propaganda documentary short subject Your Job In Germany, a.k.a. Hitler Lives (the name Warner Bros. distributed it under). He also worked on 1947 Best Documentary Feature winner Design For Death. With success in documentaries, he went on to try feature films. 1953 saw Seuss write and design the musical fantasy The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T.

One of his most famous books led to him presiding over a publishing line at Random House. Geisel’s 1957 classic The Cat In The Hat came about in response to the famous contemporary article Why Johnny Can’t Read, which partially blamed the problem on bland reading primers in schools. Dr. Seuss was actually mentioned in the article as an appropriate choice of illustrator, since his drawings encouraged rather than stifled imagination. This led to two publishers asking Geisel to try writing and illustrating a reader. His original publisher, Houghton Mifflin, retained textbook rights, while Random House got retail rights. When writing The Cat In The Hat, Geisel’s goal was to make an interesting and fun book, in contrast to the simplistic and boring books that kids had normally been given to read in school. Still using only “approved” words from the Dolch reading list, he managed to create a story capable of entrancing and entertaining young readers. The success of The Cat In The Hat resulted in the creation of the Beginner Books line, a division of Random House overseen by Geisel and his wife, Helen Palmer (whom he had met during his brief stay at Oxford, and married in 1927). Many of these books were written and illustrated by Geisel under the Seuss name, while some books were handled by others. Occasionally, he would write a story as “Theo LeSieg”, to be illustrated by someone else. Former Random House President Bennett Cerf once remarked that he considered Geisel the sole genius out of all of Random House’s popular authors.

“Dr. Seuss” was a household name by the time that Helen died in 1967, and Geisel remarried the following year, to Audrey Stone Diamond. He won the Pulitzer Prize in 1984, just one of many awards he received in his lifetime. Mr. Geisel died on September 24, 1991, but Dr. Seuss shall live forever on bookshelves, in libraries, and in the hearts of his innumerable readers.

I have purposely left out some details in his life story, though. So, on now to Dr. Seuss’s animation legacy…

Obscure Animation

Probably even some of the biggest toon buffs out there have not heard of the earliest of the Seuss cartoons. In 1931, Vitaphone released two animated shorts distributed by Warner Bros., titled ‘Neath The Bababa Tree, and Put On The Spout, that were apparently advertisements for the Flit bug repellant. Dr. Seuss received some sort of credit on them, but as they are lost films there is more speculation than fact to be had. Geisel may have written them, or even done some animation on them, or they may simply have used his designs.

Dr. Seuss Brings Horton To Bob Clampett And Gets Looney

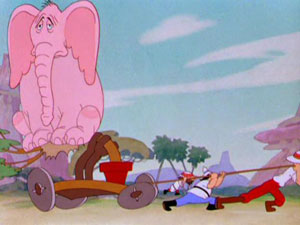

Horton Hatches An Egg was the fourth Dr. Seuss book, having been published in 1940. It concerned an elephant who agrees to sit on an egg for a bird that ends up disappearing for a good long time. Warner Brothers animation director Bob Clampett loved the book, and he pitched an animated adaptation to his boss Leon Schlesinger. The 1942 cartoon short of Horton was a charming success, due largely to its faithfulness to the source material, and it stands as the only book truly adapted by the legendary Warner Bros. animators.

(Horton got a sequel when Geisel wrote Horton Hears A Who in 1954. This story introduced the “Whos” that became even more famous in The Grinch Who Stole Christmas. The second Horton story was adapted by another Warner Bros. veteran, Chuck Jones, for a 1970 Peabody Award-winning television special. And, of course, Blue Sky made a CGI feature out of it in 2008.)

The Puppetooned Seuss

George Pal, producer of the Puppetoons series, made two animated shorts using Dr. Seuss stories. The Puppetoons were brilliant shorts utilizing stop-motion animated figures, many of which can be seen on the DVD release of The Puppetoon Movie. 1943 saw The 500 Hats Of Bartholomew Cubbins released, followed by 1944’s adaptation of And To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street. Both were narrated by actor Victor Jory, and the latter had live-action bookends. As wonderful as the Puppetoon Movie DVD is, it sadly does not include the Seuss films, but you can see snippets of them in the documentary In Search Of Dr. Seuss.

Private Snafu Joins Seuss In The Army

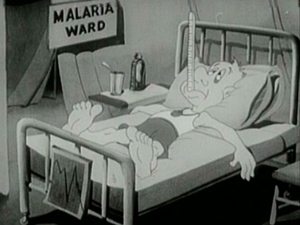

Meanwhile, while working in the Armed Forces Motion Pictures Unit under Hollywood director Frank Capra, Geisel was enlisted to head the animation branch and to assist in the development of the “Private Snafu” series. The character has been credited as being created by Geisel and Phil Eastman, although spearheaded by Colonel Capra. For those that don’t know, “SNAFU” is an acronym meaning Situation Normal All F*bleep*ed Up; this word was popular among enlisted men at the time. Private Snafu was the personification of this notion of bad mojo, and was to serve as an example to the men of what not to do. The shorts, along with live action training or informative films, were to be attached to various entertainment films sent overseas to servicemen as part of the biweekly Army-Navy Screen Magazine newsreel.

In each episode, Snafu would learn through experience how to be a poor soldier, with the hope that the real soldiers watching would learn from Snafu’s mistakes. Snafu had his own Jiminy Cricket-like conscience/advisor, a Technical Fairy, First Class.

The artistic collaborators were determined through a bidding process, with a few different cartoon studios showing interest. Walt Disney, who did produce many cartoons for the war effort, put in a bid, but he wanted to retain character ownership and merchandising rights. Instead, the Leon Schlesinger studio won with a much lower bid (by two-thirds). Schlesinger’s studio output was normally distributed theatrically by Warner Brothers, but now such directors as Friz Freleng and Chuck Jones were to be at the disposal of Dr. Seuss himself. Mel Blanc was also on hand to provide voices, including the voice for Snafu, and Carl Stalling provided the music. UPA also did two Snafus as part of their A Few Quick Facts series. After a disagreement between Schlesinger and the Army, his studio stopped working on Snafus, and Harman-Ising did one; the Tex Avery unit at MGM also did one, but although it was completed it was never filmed since the war ended before it could be shot.

Snafu’s scripts definitely showed Seussian flair, often containing sing-songy lyricism and rhyming. They also had things that one would not find in a Dr. Seuss book or a Bugs Bunny cartoon— like cursing, bare bottoms, and booby jokes— since they were not subject to Hollywood censors. And like the Looney Tunes of the time, the Snafu films had racial caricatures of Japanese and Germans, in keeping with the wartime desire to dehumanize the enemy.

The idea of the Snafu shorts was met by skepticism in some quarters, but turned into a great success. They were very popular with the men, and were effective in teaching lessons to troops that were often relatively uneducated or naïve. Twenty-eight Snafus were made between 1943 and 1945, and they can be found on a DVD called The Complete Uncensored Private Snafu.

Dr. Seuss Goes Boing Boing

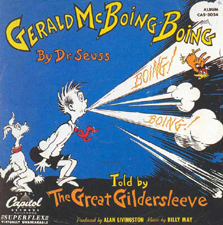

Theodor Geisel had yet another creative outlet that I have not mentioned yet. He wrote a children’s record called Gerald McBoing Boing, which was adapted by the UPA animation studio in 1951. UPA was a trendsetter in those days, known for a highly graphic style that eschewed realism. Its cartoons were cartoony in the best sense— backgrounds were often highly stylized with strong perspective and bright splashes of color, and motion was simple but exaggerated. The UPA cartoons were sophisticated in their artistic sensibilities, making them appeal to critics and intellectuals; but they were also very entertaining. Still, Gerald McBoing Boing stood out from the rest of their output, winning an Oscar for Best Animated Short Film. It was also voted #9 in the “50 Greatest Cartoons” survey of a few years ago, and featured in Jerry Beck’s book of the same name.

Gerald was a young boy who spoke only in sound effects, which was certainly a different twist. The novelty of the character extended to the artistic conception of the film, with the artists striving for visual simplicity in order to focus on the sounds and ideas in the film. They seemed to be more inspired than usual, thanks to the magic of Seuss. The characters were little more than rounded stick figures, and the backgrounds had no lines to define walls, floors, or ceilings. Instead, items on a wall (like a clock or picture) were placed and drawn in careful perspective to suggest the form of a room; sometimes just a splash of flat color would suffice to define a wall. After that successful first short, three more followed; but those lacked a Seuss script and were not as successful. Gerald still got a thirteen-episode run of an early television show, where he hosted a program that showed new and old UPA cartoons. The Gerald McBoing Boing Show appeared on CBS for the 1956-57 season. Gerald also shared a five-issue comic book run with fellow UPA star Mister Magoo, as well as being featured on numerous licensed goods. Gerald also appeared with Magoo in a television short, and as Tiny Tim in the Magoo TV special Mister Magoo’s Christmas Carol.

The Television Specials

Dr. Seuss forever was immortalized on celluloid when his 1957 book How The Grinch Stole Christmas was adapted by Chuck Jones for a 1966 television special. Jones, of course, was an associate of Geisel from the Snafu days, so Geisel was receptive to the idea of working with Jones again. It has been reported that he did have reservations about expanding the simple story enough to fill a half-hour special (one wonders what Geisel would have thought of the bloated live-action version with Jim Carrey), but as you all know the result was a holiday classic. Geisel even wrote a new song for the cartoon, You’re A Mean One, Mr. Grinch. This special led to many more specials, beginning with another Jones collaboration, the aforementioned Horton Hears A Who! from 1970.

Following Horton, Seuss worked with animation studio DePatie-Freleng Enterprises on a series of specials. This meant another Looney Tunes reunion, of course, as Friz Freleng himself was one of the head men at the studio. DePatie-Freleng churned out several Seuss specials in the 1970s, beginning with The Cat In The Hat in 1971. The Lorax came in 1972, Seuss On The Loose in 1973 (this included short cartoons for The Sneetches, The Zax, and Green Eggs And Ham), and 1975’s The Hoober-Bloob Highway. The Grinch made a return in the DePatie-Freleng cartoon Halloween Is Grinch Night, a 1977 special which won an Emmy. An Emmy nomination also came for the 1980 special Pontoffel Pock And His Magic Piano.

The last Emmy win for a Seuss project came for The Grinch Grinches The Cat In The Hat, a 1982 special that wonderfully combined Seuss’s two most famous creations. This special began as a DePatie-Freleng effort, but in the end came out of Marvel Productions, as the studio was renamed when Marvel Comics took it over. The De-Patie-Freleng specials are all available on various DVDs from Universal, or all together on one disc called Seuss Celebration.

In 1986, Thidwick, The Big-Hearted Moose was adapted in a ten-minute short produced in the Soviet Union. With artwork painted on glass, it is among the more unusual but enchanting Seuss adaptations to look at. Bizarre but great on a different level is Ralph Bakshi’s The Butter Battle Book. This 1989 TV special, done for Turner Entertainment, was extremely well animated, but perhaps the least kid-friendly of all the TV specials, with its anti-war storyline and open ending. Turner had one more Seuss project commissioned, when Hanna-Barbera adapted a late Seuss-written book, Daisy-Head Mayzie, in 1995. The special came out ahead of the book itself, a book that was not illustrated by Seuss. Nevertheless, the special was a success; and, following tradition, it too was nominated for an Emmy award. The Turner specials are available along with the Horton cartoons on the recent Horton DVD.

In Closing…

Dr. Seuss’s contribution to children’s literature is undeniable, and in researching this article I discovered that his talents took him into a great many other areas. My admiration for the man has grown along with my surprise as I turned up each new tidbit of information. When I started writing this article, I already had an outline ready and thought I knew what I was going to say; however, I ended up having to add a few sections to accommodate the new information I was discovering during my research. I am pleased to have this platform to share Dr. Seuss’s legacy with you, especially to acknowledge his contribution to my favorite art form. Now, if you will kindly excuse me, I think I’ll go read Green Eggs And Ham again. It’s my daughter’s favorite. What fun it is to share it with her!

As usual, I relied on numerous websites for information. I acknowledge them here:

Carol Hurst’s Children’s Literature Site: Dr. Seuss Feature

Dr. Seuss Index by Raymond Hamel

Dr. Seuss at infoplease

The Dr. Seuss Web Page

Catalog of Political Cartoons by Dr. Seuss

Don Markstein’s Toonopedia

Dr. Seuss adaptations at Wikipedia

Private Snafu at Wikipedia

Seuss and Vitaphone Information

More on Seuss and Vitaphone

Seuss biographical information

Seussville bio

The Big Cartoon Database

The DePatie-Freleng Website

Plus, Leonard Maltin’s Of Mice and Magic (and The 50 Greatest Cartoons) again proved indispensable.