In C.S. Lewis’ Prince Caspian book, victory is brought to the Old Narnians by the Awakened Trees that push the Telmarine Army back to the Great River where the Beruna Bridge is no more, destroyed the day before by Bacchus and his people the day before, liberating in the same move the River God in a poetic display of ivy and hawthorn.

In C.S. Lewis’ Prince Caspian book, victory is brought to the Old Narnians by the Awakened Trees that push the Telmarine Army back to the Great River where the Beruna Bridge is no more, destroyed the day before by Bacchus and his people the day before, liberating in the same move the River God in a poetic display of ivy and hawthorn.

But for the movie, director Andrew Adamson decided to make the destruction of that bridge the climax of his film, both in story and visually, with the River God himself coming to the rescue to defeat the Telmarines, in an impressive and splashing display of furious water.

Not a small challenge, technically speaking. But an exciting one for the person who had already succeeded in art directing the building of Miraz’s Castle or the final battle at Aslan’s How, as you’ll read in our previous articles on the subject.

Celebrating the occasion of Prince Caspian‘s release on DVD and Blu-ray, we welcome again Frank Walsh for an ultimate insight and the last – but not least – episode of our series on the art direction of the second chapter of the Chronicles of Narnia movie saga!

First view of the location

Animated Views: So, tell me, Frank. What will your last story on Prince Caspian be about?

Frank Walsh: Towards the end of Prince Caspian there is a climactic scene where the Telmarine Army, lead by King Miraz, march against the Narnians. Andrew Adamson, the director wanted to precede the final battle by setting Miraz the challenging task of having to ford a monstrous river to reach his enemy. In much the same way Julius Caesar, in 56BC, had taken his army against the Germanic tribes by a building bridge across the Rhine, so Andrew set us the task of achieving the same for his film. Caesar accomplished this task allegedly in 10 days; we had 40, accompanied by the predictable ‘flood’.

Frank Walsh and Location Manager James Crowley trying to keep their feet dry!

AV: First of all, how did you manage to find the right location for the shooting?

FW: Extensive scouting worldwide produced a river and valley in Slovenia matching the scale of Andrew’s vision, and the other large vistas he was going to shoot in New Zealand. The Bovec River fed by glacier melt is a truly breath taking location, and I first visited it with Andrew and Roger Ford, the production designer, in early winter. The river swollen, by the snowmelt, was almost a raging torrent, some 60 metres wide and around 4-5 metres deep in the centre. I recall standing in the middle of a group of producers, all eyes on me, as I contemplated if it was a fools undertaking or not: not quiet sure they believed me when I said it was achievable. Not too sure I was totally convinced, but I felt confident that I had a good team around me to make it happen.

An ambitious, not to say dangerous, undertaking that was going to be additionally complicated by severe restrictions such as difficult access, its close proximity to national parkland and local downstream habitation. The major stipulations, by the authorities, being that we could not introduce any materials that might endanger the environs ecologically. Anything built, then had to be removed entirely afterwards, leaving no trace, and any construction undertaken would have to withstand the potential ‘hundred year’ climatic catastrophe that might endanger any communities downstream.

Director’s recce, note color of the water, from the glacial melts

AV: How was the design of the bridge created?

FW: Although Slovenia does not have a long history of large-scale western feature films, we were fortunate to source a good local art director, who, like myself, and many of my key team, benefited from a background in architecture. This was critical to make sure that the permissions with the local river authority and various ministries would be professionally addressed, and backed by our Slovenian producer; we worked through all the objections that were raised.

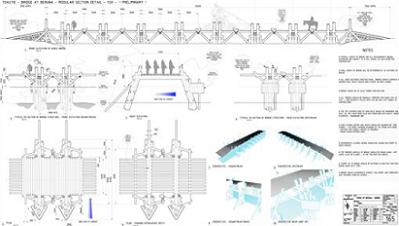

One of several CAD drawings of the Bridge

The design of the bridge had to appear to be made from quickly felled trees, however it had to be strong enough to take the shooting unit, cast and extras in all weathers and withstand the extreme river forces, whilst being quick and easy to build and dismantle.

Detail from the CAD drawing

Due to the local geographic conditions and constraints put upon us by the Slovenian authorities, we felt we should employ a recognised bridge building company to ensure the safe installation, which would adhere to all the relevant codes of practice. Several companies pitched for the work, and eventually Primorje, a civil engineering company of some reputation, won the brief. Although they had not built a bridge based on a 2000-year-old concept, however liaising closely with them we designed a workable solution that fulfilled all the criteria.

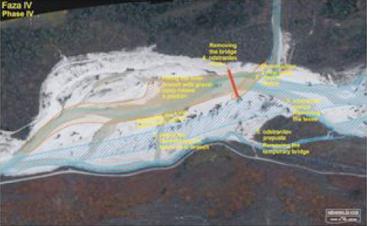

Art department model, the red lines indicate the proposed rerouting of the river

The actual bridge design team in Prague was lead by Phil Sims, who produced complex computer aided design drawings for official approval, and also to better acquaint the construction team with exactly how the bridge should appear. The building materials appearing to be roughly hewn by axes, rather than cut with power saws and adding dummy wooden pegs to hide fixing bolts, for instance, was a major visual effect we had to capture. As usual, our producers wanted to spend as little money as possible, so very tight financial control was essential. This formed my biggest headache as unforeseen problems arose throughout the realization of the project.

Location plan showing normal flow of the river

A very large, room sized model was constructed of the river and bridge, that we could manipulate the position and better understand how it would look in the river. This was also a useful tool when Andrew and Roger were in New Zealand. Using mini cameras, we set up live video links to them, so they could look at the model and discuss any concept or design issues directly with us in Prague.

Planned rerouting of the river, so the bridge can be built safely

AV: How did it take to build such a bridge?

FW: Apart from the issues in creating a bridge as I described earlier, there was the problem of the build and shooting schedule. We were only allowed a very small construction period, so as not to disrupt the social use of the river by canoeists etc. With shooting scheduled to be during the summer, and also the need to move at great cost, so many of the filming crew from Prague, the schedule dictated a bizarre arrangement of building order. In the script the Bridge is first seen being built and Andrew wanted to show how the Telamarines were felling a whole forest to achieve the task. Then we see the army crossing on their way to Narnia. The troops are then seen retreating across the Bridge, where the River God destroys them and the Bridge. Finally we see Aslan and the children on the riverbank with the destroyed bridge.

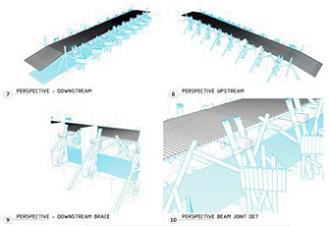

Visualisation by the art department to show how the bridge would look

To achieve this, we would first build the bridge as a full complete structure, capable of actually taking our ‘Army’. All the scenes of crossing and the retreat were then filmed. The schedule allowed for two days originally, (but in reality more like one) to dismantle half the bridge, for the arrival scene to be filmed, and then finally overnight, everything left, had to be ‘creatively’ wrecked for the aftermath of the River God’s attack.

Apart making sure the bridge appeared correct for the film, the biggest issue was how to build such a structure, made up of individual components in a fast flowing river, without making permanent piled fixings into the river bed (prohibited because we had to guarantee returning the river to its original state). After much head scratching we proposed completely diverting the river temporary, to allow the bridge to be erected in the ‘dry’. This the authorities accepted after much discussion and submission of water flow data etc to prove it was a safe solution.

Overview showing new forest and Bridge, and the secondary unit access bridge

over the feeder tributary, before the river was rerouted back to the old course

The procedure we adopted was as follows:

Phase 1: Excavating a trench on an existing raised area in the middle of the river.

Phase 2: Opening the trench upstream to allow the river to follow a new path, south of the existing main water flow.

Phase 3: Build a dam wall in gravel/stone, to block the reduced flow running down the old river course, and direct all the water down the new route.

Phase 4: Construct the bridge in relatively dry conditions, protected by the dam wall.

Phase 5: Upon completion of the bridge build, and its safety certification, the dam was removed and the river returns to its old course, now flowing under the new Bridge.

Phase 6: The trench is filled in and no trace of the excavations left (to avoid any changes of the water course later that might upset the unique topology of the river here and further downstream).

Finished Bridge, showing drained riverbed looking downstream

This approach also allowed us to achieve another of Andrew’s stipulations, in that the water had to appear to be deeper, especially if there was reduced flow due to the summer heat. We originally wanted to build a dam downstream to maintain a fixed height of water, but the authorities had refused this. So our excavations allowed us to dig out some deeper parts either side of the bridge, so it appears that the retreating army are in water deep enough to drown in.

Finished Bridge, showing drained riverbed looking upstream

The responsibility for the on ground build was passed to my most experienced art director, Dave Allday assisted by Katja Soltes, the local art director who had guided the project through the complex permissions stage for me. Their task was to supervise and trouble shoot the installation, ensuring that whilst we completed a sound and safe bridge structure that it also complied visually with the parameters of the film. Naturally, their presence during the revamps was crucial to ensure that we hit the schedule set by the production, and to keep the set looking as it should appear in the film.

The river rerouted back under the Bridge. At the top of the picture

a second new access bridge, installed by Frank Walsh and team

for the filming period, can just be seen, concealed by more trees

AV: Did the location itself have to be re-designed too?

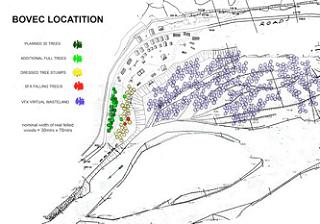

FW: Despite the natural beauty of the location, Andrew felt there were insufficient trees close to our building area, especially on the Narnian bank. So our Greens Team under Jon Marson had the task of sourcing full size trees to place in the dry shingle bed of the river.

Overview showing the Bridge in its second redressed state during

the revamp, a crane being used to remove bridge sections

Over 100 trees and large amounts of under foliage and forest floor were needed for this. Due to the local constraints however, these entire alien flora had to be kept separate from the river, and everything had to be completely removed after filming. To achieve this, entailed driving plastic drainpipes tubes vertically into the riverbed, in which to anchor the trees, and placing a plastic carpet across the ground so the new forest floor would not seep into the river. All this work occurring during one of the hottest periods of the year meant there was a constant battle against the tree becoming brown and dead looking.

One of the 100 trees being carefully placed in position

Luckily there was plentiful supply of water close by to keep spraying the leaves, but it required constant attention from the team throughout. Due to the location position, each tree had to be forested in a sustainable wood, which was some 15kms away. In shipments of between one and three at a time depending on size, they were then transported by lorry, manhandled individually by mechanical crane through the river, and placed securely in position. Usually they sustained some wear and tear during this process, so often branches had to be replaced and any other damage concealed.

View from Narnia bank, showing the new ‘forest’ in the

foreground, and camouflaged access bridge across side tributary

On the Telmarine bank, they also had to also install hundreds of cut tree stumps, to make it appear that Miraz had cut down the forest to provide the building materials. Most came from the same trees that were felled for the forest extension on the other riverbank, and to maintain our commitment to being ecologically responsible, after filming all the trees and like the bridge materials were removed and sent for recycling.

View looking upstream, showing added tree stumps and the

dressed ‘Camp’ beyond. Camera by red dots indicated on plan below

The remaining forest dressing was also removed and the site cleaned back to return it to the state as we had found it originally. The only trace being access routes we had installed along the north bank, which were retained as part of the local long-term plans to upgrade the river as a leisure amenity for the local community and visitors to the area.

Design plan for trees and shows part of this area of the river downstream of

the Bridge, created for the scene where the children first see the construction.

AV: Then was the set-dressing part. How did you accomplish that?

FW: The set-dressing department, headed by Kerrie Brown had to decorate the riverbank to make it appear there was an encampment for an army of thousands, as per Andrew and Roger’s brief. This required the design and making of hundreds of tents, workshops, forges, log stacks etc, etc, along the Telamarine riverbank. Obviously, all of this dressing had to be installed at the last moment due to flood danger, and of course the predictable happened!

The Bridge finished waiting for the river to return…..

Heavy rains descended and the river rose. At one point just before filming it appeared that a disaster was imminent, as some lower lying areas disappeared under water, with dressing being swept away. Miraculously, the waters receded just before the 1000 strong unit turned up for filming, and before the river had inflicted much irreparable damage. It felt as if the River God was actually there, but had been in a benign mood that day, but a warning none the less, not to anger him.

The rising river threatens the Bridge, the water

level having risen by two metres overnight

AV: How did you integrate visual and special effects?

FW: The 2nd Unit were the first to arrive, a few days before the main unit, to shoot the main army sequences, and the wide shots required by the visual effects department. Certain scenes required actors to appear to interact with the River God, which would later added digitally. This required careful coordination especially in making sure eye lines, to this ‘invisible’ figure, were accurate so they appeared to be looking at the right angle and position. Discussion with the visual effects department early on, about how we could achieve this, explored initially the idea of using a large weather balloon attached to a motor driven winch. However, issues such as wind control negated this idea, so ultimately a miniature helicopter, skilfully flown, was used to place the River God’s head in the correct position.

Rising waters threaten the Telmarine camp

Andrew also wanted to see the actual river level fall as the river God rose up out of the surging waters. Naturally this was impossible to achieve neither practically by altering the river flow because of the veto on damming the river, nor by building any special mechanical rigs, due to the risk of contamination to the water from the equipment. So, as is often the case, the best solution being the simplest, the actors just bent their legs to look as if the water level was rising and falling.

In scenes where the bridge is seen being lifted and then destroyed completely, a combination of real physical effects were used in the river, water cannons, high-pressure hoses and so forth to establish the destruction, and for close ups. However, the visual effects team needed some key pieces to be physically moved and shattered. This was impossible to do due to time, costs and other ecological considerations in the Bovec River as a real effect.

To achieve what they asked for, after filming was completed in Slovenia, some bridge parts were shipped back to Prague, rebuilding them on purpose made rigs, against massive green screens outdoors. To assist the visual effects and editors, before the rebuild, we had to carefully plot the orientation of the bridge pieces in relation to the sun path, to exactly match the footage already shot in Slovenia. Individual shots could then be perfectly intercut, without shadows moving distractingly. One bridge section was built on a steel frame with a twisting motion, which using balsa wood planking for safety, bits of the bridge could be violently broken off around the stunt men. Another large section was built on a hydraulic tilting rig, strong enough to carry a horse and rider safely, which could be angled up to almost 45 degrees. It was an astonishing sight to see how our specially trained horses where able to take such an inclination without fear, having absolute trust in their Spanish stunt riders. Visual effects then had all the physical elements they needed, to composite into their digitally created parts, to produce film as you now see it.

AV: Once again, you share with us behind-the-scenes stories that are adventures in themselves. Thank you so much for all that!

FW: Hopefully the audience enjoyed the sequence, and the foregoing will expand the appreciation of what went into making it happen. I would like to take this opportunity to acknowledge the contribution made by my team and our Slovenian colleagues who helped realize this challenge set by Andrew.

Collector’s Edition is available to buy now from Amazon.com

With all our thanks and gratitude to Frank Walsh.

For more on the making of the Beruna Bridge, several clips are available on YouTube, the third of which can be viewed here.