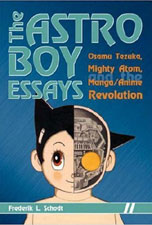

The Astro Boy Essays: Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, And The Manga/Anime Revolution

The Astro Boy Essays: Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, And The Manga/Anime RevolutionBy Frederik L. Schodt

Stone Bridge Press

September 1, 2007

Paperback

248 pages

$16.95

Animated Views is very pleased to present a book review by a guest contributor, Raz Greenberg. Raz is an avid student of animation, and has written and lectured on the subject. This is his first review for Animated Views.

Frederik L. Schodt is a scholar of Japanese culture, known mostly for his work on manga (Japanese comics), as both a translator and as a researcher of the subject. His books Manga! Manga! The World Of Japanese Comics (1983) and Dreamland Japan: Writings On Modern Manga (1996) have achieved a status of canonical texts among those wish to study the field. In his new book, The Astro Boy Essays: Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom And The Manga/Anime Revolution, Schodt examines the life and work of the man who is perhaps the most prominent figure in the history of Japanese comics – and who also played a major role in shaping the animation industry of the country.

Osamu Tezuka (1928-1989), considered to be the “God of Manga”, has earned the title due to the massive output of comics he drew (estimated to be around 150,000 pages) in the post-WWII era. He created dozens of memorable heroes in different genres that defined and paved the way for artists who followed in his footsteps ever since. With such a prolific career in comics, it should come as a surprise that in his short life Tezuka had time for other projects – but the role Tezuka played in the history of Japanese animation is at least as significant as his work in comics.

For Schodt, Tezuka was more than an important artist – the two were friends, and Schodt also served as Tezuka’s interpreter. Tezuka wrote the introduction to Schodt’s book Manga! Manga!, and Schodt devoted an entire chapter discussing Tezuka’s life and work in his later book Dreamland Japan. Other scholars – notably Fred Patten in his essays anthology Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004), also discussed Tezuka; but The Astro Boy Essays is the first book in English devoted entirely to Tezuka and his work, albeit from a very narrow focus.

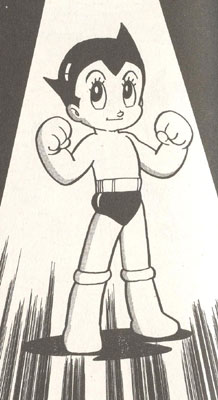

As the title suggests, The Astro Boy Essays is basically about the development of Tetsuwan Atomu, or “Astro Boy”, as he was known in English – the futuristic boy-robot, Japan’s answer to the American superheroes, and one of Tezuka’s most iconic characters in both comics and animation. In terms of cultural significance, Tetsuwan Atomu was the Japanese equivalent of both Superman and Mickey Mouse. Other titles and characters from Tezuka’s enormous body of work are also mentioned throughout the book, but barely discussed: the story of Tezuka and his work is told through Astro Boy almost exclusively. So, The Astro Boy Essays may be the first book in English devoted entirely to Tezuka, but it focuses on only a fragment of his work— a very important fragment, to be sure, but still only a fragment. As Schodt explains in the introduction, a book trying to deal with all of Tezuka’s work would have been monstrous in size, and there’s also the problem of many American readers not being familiar with Tezuka’s lesser-known and more serious works (though in recent years some of these works such as Phoenix and Buddha actually became widely available in translation). The Astro Boy Essays is more of an introductory text, an initial analysis of Tezuka’s work rather than an attempt for a thorough look at his entire career. And as such, Schodt presents it in his usual fascinating, though-provoking manner.

As the title suggests, The Astro Boy Essays is basically about the development of Tetsuwan Atomu, or “Astro Boy”, as he was known in English – the futuristic boy-robot, Japan’s answer to the American superheroes, and one of Tezuka’s most iconic characters in both comics and animation. In terms of cultural significance, Tetsuwan Atomu was the Japanese equivalent of both Superman and Mickey Mouse. Other titles and characters from Tezuka’s enormous body of work are also mentioned throughout the book, but barely discussed: the story of Tezuka and his work is told through Astro Boy almost exclusively. So, The Astro Boy Essays may be the first book in English devoted entirely to Tezuka, but it focuses on only a fragment of his work— a very important fragment, to be sure, but still only a fragment. As Schodt explains in the introduction, a book trying to deal with all of Tezuka’s work would have been monstrous in size, and there’s also the problem of many American readers not being familiar with Tezuka’s lesser-known and more serious works (though in recent years some of these works such as Phoenix and Buddha actually became widely available in translation). The Astro Boy Essays is more of an introductory text, an initial analysis of Tezuka’s work rather than an attempt for a thorough look at his entire career. And as such, Schodt presents it in his usual fascinating, though-provoking manner.

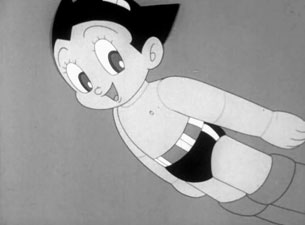

The book’s opening chapters describe the cultural phenomenon Tetsuwan Atomu came to be in Japan, and then provide a short biography of Tezuka himself, his early stylistic influences, and how the character of Atomu and the world surrounding him developed from Tezuka’s original concept. For those chiefly concerned with the animated incarnation, however, things start getting interesting around chapter 4, which describes how Atomu made the transition from comics to TV animation, eventually revolutionizing the Japanese animation industry. Again, there is a discussion of the artistic influences on Tezuka from other animators, in particular Disney and Fleischer, along with the revelation that Tezuka actually considered a career in animation long before he turned to comics, and in fact created a 20-second animated short as kid. Schodt also reminds the readers that Tezuka was not working in a vacuum, and that an animation industry existed in Japan long before he set up his studio, Mushi Production, to adapt Tetsuwan Atomu into an animated TV series in 1963. At the same time, however, I also got a feeling that Schodt – while openly admitting that by today’s standards, the 1960s series looks crude – is somewhat too forgiving towards the cheap, time-saving animation techniques Tezuka employed in his studio. Tezuka can hardly be blamed for inventing limited animation techniques for TV productions (Americans were there at least a decade earlier), but he did make it popular enough to encourage many other studios to jump on the wagon. Japanese animation received a stigma for making things quickly, cheaply, and without much care for quality, a stigma that would accompany it for many years to come. Tezuka’s success, therefore, certainly led to the enormous output of animation coming from the country to this very day, but it did so at a price.

Yet Tezuka made another achievement – perhaps his most significant achievement – when he managed to sell the Tetsuwan Atomu animated series, now renamed Astro Boy, for broadcast in the United States, where it became a hit. This made Tezuka the first man who managed to popularize Japanese animation in the West, a task others before him (in particular the Toei Studio, with its lush and expansive productions) failed to do. And the fact that he did it with a black-and-white series, at a time when color broadcasts were taking over in America, makes it even more amazing. The fifth chapter in Schodt’s book deals with the American reaction to this cultural import, and in my opinion, it’s the best chapter in the entire book. The story of how cultural differences between Japanese and Americans were reflected in the show and had to be resolved through dubbing and editing is fascinating enough, but Schodt also explores just how deep an impression Tezuka made with the show on key figures in the American film industry, some more likely to have noticed it (Walt Disney), some less so (Stanley Kubrick).

At this point the book moves back to discussing the character of Atomu/Astro Boy at large, its influence on manga and anime that followed it, its influence on readers, its cultural significance, and how Tezuka’s personal ideology fit into everything. As readers of Schodt’s previous books already know, he is every bit as talented in making cultural analysis as he is in documenting history, and this part of the book also makes a very interesting read.

The final chapter of the book deals with Tezuka and his iconic hero in the years following the bankruptcy of Mushi productions. Here Schodt reveals some of Tezuka’s shortcomings, mainly the fact that for all his success, he wasn’t a particularly good manager or businessman. In this chapter, Schodt also gives some quotes from people in the Japanese animation industry who weren’t too happy about the working and quality standards Tezuka introduced. As Schodt demonstrates, the success of Atomu/Astro Boy actually became something of a burden for Tezuka himself in his later years, as he tried to take his work in a more serious direction – strongly evident in the production of a new color animated show about the character in 1980, which unsuccessfully tried to balance between the artist’s old and new sensibilities. It’s here that the limited scope of the book becomes a problem, when it barely touches upon the fact that, in the same decade, Tezuka actually became a critical darling in the global animation community thanks to experimental shorts like Broken Down Film, Legend Of The Forest and Jumping. Readers unfamiliar with Tezuka’s post-Mushi animation career might finish the book concluding that while as a manga artist he moved from Tetsuwan Atomu to bigger and better things (a point Schodt makes very elaborate), he hardly made the same artistic progress as an animator.

Reservations aside, Schodt has again managed to produce a wonderful book, a much-needed first comprehensive study in English about one of the most important people in the history of both comics and animation. Hopefully, both Schodt and other writers will follow with future studies of Tezuka’s work.