Popeye the Sailor has long been one of the most popular and recognizable comic strip characters in the world. In all honesty, he seems to be well past his heyday, with his daily comic strip now in reruns and no new cartoons having been made for years now outside of that odd CGI special; but he is still a legend. Things appear to be on an upswing for the ol’ sea salt, however, as his original comic strips have come back into print in a deluxe book line from Fantagraphics, and of course his legendary cartoon shorts from the Fleischer studio are finally coming to home video for the first time in an authorized edition. With the renewed attention being given to Popeye, it is a good time to look back at what has made him a pop culture icon for so many decades.

The Genius From Chester

The Sailor began his career in a rather unassuming way, as a bit player in an already well-established comic strip by E.C. Segar (1894-1938). The Chester, Illinois native had been a motion-picture projectionist at one time, known for making chalk drawings on the sidewalk by the Chester Opera House in order to advertise what was playing inside. When he was old enough, he traveled to Chicago to become a newspaper cartoonist. Some good connections led to an assignment on Charlie Chaplin’s Comic Capers, which in turn led to him taking on an illustrated feature that reviewed entertainment happenings in town, called Looping The Loop. A man in the Hearst newspaper organization noticed his work, and Segar was offered the opportunity to come to New York to work for Hearst’s King Features Syndicate. It was there that he was directed to work on a comic strip that was to be named Thimble Theatre in 1919.

Segar chose as his characters the oddly named Oyl family: siblings Castor (a fairly benevolent schemer) and Olive (skinny, but somehow something of a guy magnet), their parents, and Olive’s boyfriend, Ham Gravy. At first, the strip followed the gag format, with each day’s events unrelated to the others. Over the next ten years, though, Segar became fond of continuity, and weekly themes evolved into telling actual stories. This opened up the narrative considerably, and allowed for the introduction of more complex elements, such as ongoing plots and a wider array of characters. Segar became known for his many zany creations, who usually only showed up for a single sequence and were never seen again. The Oyls and Ham Gravy were often, relatively speaking, the “straight men” in the affair, although they certainly had their share of foibles and odd traits.

The daily strip had been doing well enough, telling enjoyable stories of uncommon wit and playfulness, and a Sunday color page was added in 1924; but a storyline that began in late 1928 would see the strip altered forever. In this story, Castor and Ham had decided to travel to Dice Island with their luck-producing Whiffle Hen in order to make some quick cash. They got themselves a boat, but needed a man who knew how to sail it. Searching around for a suitable-looking fellow, Castor spied a runty-looking older fellow with one eye, smoking a corncob pipe. The date was January 17, 1929.

In the next few days and weeks, the strip enjoyed a new dynamic that was mystifying. Somehow, the new character’s charm and salty sensibility brought a whole new aura to the strip, elevating it several notches above its already laudable status. Popeye, named only in his third daily appearance and never intended to stick around past his introductory storyline, ended up taking over the whole strip. Suddenly, the strip was twice as interesting and twice as funny.

Popeye’s look evolved greatly over the years, but many aspects of his character were evident from the first week of his life, especially his brusque nature. There has been some conjecture by the people of Chester that Popeye was inspired by a local man named Rocky Feigle. Rocky was a tough old coot who worked at the town saloon and was rumored to have never lost a fight. No doubt, Segar’s exposure to Feigle was an influence, just as other town residents could be seen in other Thimble Theater characters to some extent.

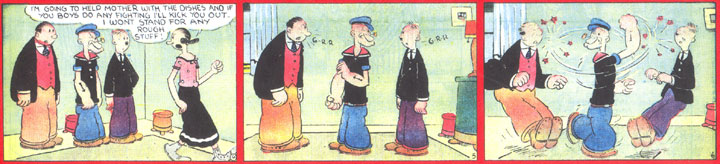

Aside from his toughness, the early Popeye was known for his uneasy relationship with Olive, which led to romance when she kissed him in August 1929 (although she said it wan an accident at the time). Even in the beginning, Popeye said “Blow Me Down” a lot (starting in just his fourth appearance), and he took no guff from anyone. He was not necessarily heroic in the traditional sense, but no one could argue the appeal of a man who was so supremely self-confident and believed in himself more than anything else. The rougher edges this attitude gave him were softened a bit in later years, as the original depiction of Popeye actually showed him to be explosively violent and physically reactionary, in ways that may seem a bit shocking today. He usually punched first and asked questions later, finding out he had decked an innocent about as often as he smashed a villain. Of course, this has much to do with the times, as Popeye came about in-between two world wars and at the beginning of the Great Depression— a time of great uncertainty when people must have enjoyed seeing a man who was unafraid to lash out and take charge. It was also very early in the history of widely syndicated entertainment, before people became more sensitive to the portrayal of violence and its effect on young readers in particular. This roughness of character seen in the sailor was tempered, however, by Popeye’s absolute sense of right and wrong. A more moral character never existed. He was a champion for his time, fighting the good fight in an unwavering way.

By 1932, Popeye had pretty much taken over as the star of Thimble Theater, much to the surprise of his creator. Several newspapers started to rename the strip Thimble Theatre, Starring Popeye, and the trend would continue to include many more papers, until eventually only the name Popeye was retained. Anyone who has dabbled in the creative arts knows that works of art can take on lives of their own, and this was certainly the case with Segar and Popeye. Popeye’s star status was proven with the arrival of scads of merchandise, mentions of Popeye by radio comedians, and loads of fan mail for the sailor. Popeye had pushed Ham Gravy out of the strip, and the daily continuities continued to churn out whimsical characters, whether for short stays or as recurring characters. More successful ones included Popeye’s enemy the Sea Hag at the end of 1929, mooching Wimpy in 1932 and his enemy Geezil shortly thereafter, Roughhouse in 1932, and baby Swee’pea (who was sent to Popeye through the mail) in 1933.

Popeye Gets Animated And Finds His Voice

Such was Popeye’s success that New York cartoon producer Max Fleischer, known mainly for Koko the Clown and Betty Boop, sought out a deal to make Popeye into an animated cartoon star. He met with a Mr. Gortatowsky of King Features, who was reportedly surprised that anyone would want to animate such an ugly character. Nevertheless, terms were agreed to, and in today’s lingo, a “pilot” was shot. Popeye was featured in a 1933 Betty Boop cartoon entitled (Betty Boop Presents) Popeye The Sailor. The cartoon featured Popeye, Olive, and newly created rival Bluto. Betty also hosted tryouts with The Little King and Henry, but only Popeye was launched into his own film series, beginning with I Yam What I Yam later in 1933. What followed were dozens of successful cartoons by Max Fleischer and his directing brother Dave. It is the Fleischer Popeye cartoons that are best loved by animation fans, due to the complexity of the animation, the often intense creativity of the stories and staging, and a certain “spark” that has never been recreated elsewhere; and, like other Fleischer works, the use of actual three-dimensional backgrounds was sometimes employed to great effect.

Naturally, these cartoons were also where the Popeye and Olive Oyl voices were first heard, and they were perfect even if little thought was given to any actual lip-synching in the Fleischer shorts. Mae Questral, of Betty Boop fame, provided Olive’s frantic wails (except for 1938-1941, when Olive was done by Margie Hines), and studio in-betweener Jack Mercer did most of Popeye’s charming stream of consciousness mutterings (taking over from William Costello after the first few cartoons; Costello was fired for making too many demands). The ongoing popularity of the films continues today, despite the fact that all of the Fleischer shorts were made in black and white; they also did three longer two-reelers in color that are marvelous.

The cartoons had a huge impact on how the public viewed Popeye and his cast, not to mention his favorite vegetable. While spinach was mentioned in the strip as being the source of Popeye’s fighting prowess, it was emphasized much more in the cartoons (probably every one of them, in fact). The self-proclaimed spinach capital Crystal City, Texas made Popeye the first cartoon character to have a statue erected when Popeye’s went up there in 1937. Spinach consumption in the United States went up by a third during the 1930’s and most of the credit was given to the powerhouse sailor. Many of you have likely seen Popeye-brand Spinach on your grocery shelves, as it has become the number two brand in the U.S.

According to Segar’s longtime assistant Bud Sagendorf, Segar created Popeye’s nemesis Bluto by the Fleischers’ request, as they needed a regular villain for Popeye. Bluto was a composite of many of Popeye’s past newspaper strip foes, and initially appeared only in the cartoons, except for one early comic strip appearance. His popularity in the shorts led to Segar including him in the strip more regularly as well, although some disagreement or misunderstanding over the name (between King Features and Paramount) in the 1950’s caused Bluto to be renamed Brutus for the comic strip and comic books.

To Segar, this popularity was a double-edged sword. He was delighted that fans of all ages had taken to the Sailor so well, but it led to Hearst telling him to tone down Popeye’s language and violence in a memo from 1934. Popeye still fought, of course, but he always had to show just cause first. To Segar, this meant that the character was diluted a little, but I like to think that it was showing Olive’s influence on him too. This seemed to lead directly to the creation of a nasty, feisty character for the strip who could make up for the softening of Popeye: Poopdeck Pappy. When Popeye found his Pappy in 1936, it allowed Segar an outlet for showing crass behavior in a humorous way, without compromising Popeye himself. As Segar continued his work on the strip, he added more novel characters. The magical Eugene the Jeep came along in 1936, becoming an instant favorite. And of course, who could forget the notorious Alice the Goon character, introduced in 1934? Hairy, evil, naked Alice was an abomination at first, but later on readers warmed up to her when she beat up the Sea Hag, got dressed, and became somewhat domesticated.

A less well-known example of Popeye’s popularity was the production of a Popeye radio program. Three attempts were made, twice by Wheatena (their shows had Popeye getting his strength form eating Wheatena brand hot cereal!), and once by Popsicle, between 1935 and 1938. Around 200 episodes were broadcast in total, although only a few of the programs exist today.

Having Found One Father, Popeye Loses Another One

Sadly, Segar died of leukemia in 1938. Today, many fans regard him as a genius of the comic strip form. His characters were stunningly original, and his stories were tremendously creative and fun. The few years that he worked on Popeye have had an enormous impact on popular culture. He was lucky to have enjoyed some of that success while he was still alive, too. Aside from the enormous popularity of the cartoons, the strip was hugely successful and made him wealthy. A 1936 magazine article placed his annual income at $400,000.

The comic strip was taken over by writers Tom Sims and Ralph Stein, while artwork was done by Charles H. “Doc” Winner, and later by Segar’s own assistants, Bela Zaboly and Forrest “Bud” Sagendorf. Sagendorf’s name will be most familiar to many fans; he assumed total control of the strip in 1958, and continued with it for many years, as well as producing many of the comic books. Sagendorf also wrote a book entitled Popeye: The First Fifty Years in 1979, and provided many new illustrations for it. His own contributions to the strip included Popeye’s Granny and Dufus. He died in 1994.

Other contributors to the comic strip included Bobby London, a former “underground” cartoonist. His six-year run came to the end when King Features fired him in the early 1990’s over what they saw as his overly contemporary and “relevant” take on the character. The current daily strips are reprints from the Sagendorf era, while the Sunday page is by Hy Eisman.

But Why So Popular?

The reasons for Popeye’s popularity must be apparent to anyone who has enjoyed his exploits, although those reasons are likely different for everyone. I believe the answer goes back to those early appearances in Thimble Theater, where his personality was already on display, even if it was a bit rough. Popeye has always been uncompromising, in a way that many of us envy. He takes charge of a situation immediately, and does not show weakness. Like all of us, he does not always understand his environment or his circumstances, but it never prevents him from coming out on top in the end. Still, he has a vulnerable side too, that shows when he gives way to Olive or has to handle little Swee’pea.

Artistically, Segar had a unique style that has been carried on by successive artists, even if there have been modifications along the way. The Thimble Theater characters are truthfully a bit ugly and bizarre, but they also have a roundness that still allows them to be appealing. The comic strip’s storylines always had something for everyone, bouncing from satire to slapstick and from drama to fantasy. The cartoons, at least the first decade’s worth or so, used a formula that nevertheless was as enjoyable as it was reliable. And all incarnations of Popeye and his supporting cast have displayed a group dynamic that is unmistakably unique and winning.

More Cartoons And Other Appearances

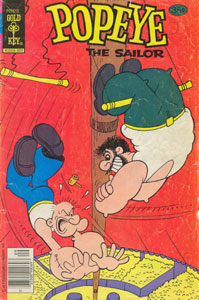

The Fleischer brothers were removed from their own studio when Paramount took it over in 1942, but the studio was renamed “Famous Studios” and continued to make new Popeye cartoons (eventually in color starting in 1943) until 1957. Changes were made in the cartoons, including white Navy uniforms for Popeye and Bluto, new clothes for Olive, and the addition of nephews for Popeye (copying Donald Duck’s nephews). By the end of the Famous run, an amazing total of 228 cartoons had been made, and they were among the first be shown on television the same year as the last one was produced. This made Popeye an early TV star, and he would continue to be a children’s favorite for decades.

During the 1960’s, King Features Syndicate decided that they wanted a piece of the action and contracted several studios around the world to produce new Popeye cartoons for television. Paramount Pictures, Jack Kenney Studios, and Rembrandt Films in Italy produced these 220 cartoons in just two years. They vary wildly in quality, with the best being described by fans as “decent” and the worst as unwatchable.

CBS and Hanna Barbera began a Popeye collaboration in 1978-1981 with their The All-New Popeye Hour ; this series, though, had to obey the current broadcast standards, thereby excising the violent aspects of the stories and making them rather drab. Future incarnations moved further yet from the heart of the characters. Hanna-Barbera carried all-new episodes in their The Popeye and Olive Show that premiered in 1982 (this was the one that had segments with Olive in the army, and Popeye as a caveman). 1987 saw the coming of Popeye and Son , which portrayed Popeye and Olive being married years before they tied the knot in the comics.

Speaking of which, the wedded union was shown in 1999 in the pages of a special one-shot comic book written by popular Hulk and Supergirl comic writer Peter David, and drawn by Dave Garcia and Sam de la Rosa. The cover was by Tom Grummett (who resides in my hometown!), best known for being one of the artists in the Death Of Superman storyline from the early 1990’s. The stunt was not reflected in the comic strip itself, though, and the Popeye-Olive-Bluto dynamic remains undisturbed in newspapers. A King Features spokesperson described the comic as a “one-shot fantasy”.

One can also not forget the 1980 Popeye live action film directed by Robert Altman and starring Robin Williams— of course, many fans would like to forget it. Personally, I have always enjoyed that interpretation, but for many observers the film failed to capture the spirit of the cartoons. I would recommend that viewers instead look at the original comic strips by Segar before passing judgment. Although there were aspects of the Altman film that were inspired by the cartoons, it is really closer in tone to the comic strip. And even if you didn’t care for the script, you have to admit that the casting was wonderful. Williams did a fine Popeye, and Shelley Duval was a terrific Olive Oyl. Ray Walston’s Poopdeck Pappy and all the smaller roles were likewise well played.

The latest frontier for Popeye-on-film was CGI, as a new computer-animated film (Popeye’s Voyage: The Quest For Pappy) was produced to celebrate his 75th anniversary in 2004. Although some fans have deemed it unsuccessful, at worst it had no negative effect on Popeye’s ongoing popularity. He remains heavily merchandised, and is still one of the most recognizable fictional characters in the world. Until the recent reissuing of the Segar comic strip and announcement of Warner’s securing of home video rights to all the Popeye cartoon series, it appeared that we would only have our childhood memories of enjoying Popeye’s exploits in papers, in comics, and in his cartoons. Those memories are worth a lot, but new books and DVDs are even better— not just for those of us who have always loved Popeye, but for our kids too!

Recommended reading:

Popeye: The First Fifty Years, by Bud Sagendorf

The Fleischer Story, by Leslie Carbaga— this has tons of further info on the cartoons, and lots of artwork

The Complete E.C. Segar Popeye, now out of print, published in 11 volumes by Fantagraphics Books

E.C. Segar’s Popeye, Fantagraphics’ redone reprint series (now in process)

Popeye: A Cultural History, by Fred Grandinetti (everything you wanted to know, and more)

Websites:

Don Markstein’s Toonopedia Popeye page

E.C. Segar info

Popeye on radio

Animation World Article

Article on the wedding