The Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, France (September 14 2006–15 January 2007), the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Montréal, Canada (8 March 2007–24 June 2007).

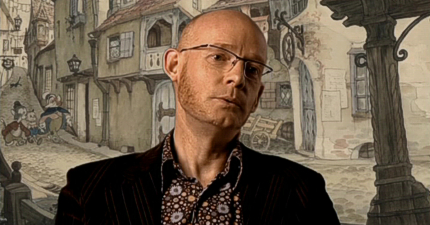

Animated News & Views’ Ben Simon travels to Paris to tour and experience the Il était une fois, Walt Disney (Once Upon A Time…Walt Disney) art exhibition at the Grand Palais, and speaks to the commissioning curator and the exhibition’s instigator Bruno Girveau about this once in a lifetime, ten years in the making event.

Paris, France: unquestionably the artistic capital of the world; home to the Louvre and perhaps the biggest “installation” of all, the Eiffel Tower! It’s also where Bruno Girveau, chief curator in charge of collections for the National Superior School of Fine Arts, Paris, unveiled his latest exhibition, a lavish and highly detailed look at many works of art from the Disney Studios’ Golden Age, complemented (and making it “accessible” to high art types!) with authentic works by such luminaries as Friedrich, Kittelsen, Dadd, Lüttner and Wasse. The connection? These Europeans were some of the artists who influenced Walt Disney and his closest animators, illustrators and background painters during the informative years of growth at his Studio. It was a time that saw such leaps and bounds as the first cartoon in Technicolor, the first full-length color and sound animated feature, and such groundbreaking films as Pinocchio and, arguably as close as animation got to “high art” aspirations, Fantasia.

During all this time, Walt found inspiration in the stories handed down from generation to generation in Europe, an inspiration fueled by a mid-1930s trip that resulted in well over 300 books being transported back to the Studio, where a library was founded for any employee to, pardon the pun, draw upon. The sources of plots, of course, were a primary consequence, though many do not realize that the look of certain sequences, of characters and indeed the very perception behind some of Disney’s works, were also inspired by these books, as well as paintings, landmarks and other sources that the artists, many of European extraction themselves, brought with them from their own cultures. Girveau’s exhibition is all about setting that record straight, highlighting not only the amazing work of many Disney artists that usually toiled away under the shadow of their admired boss, but also of the significant art and artists that dictated many of those choices.

Concentrating on Walt’s own timeline of producing animated features, from Snow White in 1937, until The Jungle Book some thirty years later, Il était une fois, Walt Disney strives to uncover these influences, many of them surprising even to seasoned scholars. It seems the Disney films are bursting with such references, from the 13th Century sculpture of Queen Uta at Naumburg Cathederal, Germany, that influenced Joe Grant’s conception of the Wicked Queen in Snow White, the paintings of Dulac and Jank that so influenced Eyvind Earle’s work for Sleeping Beauty, and even so far as to the artists quoting the movies they were watching of the day: back to the Wicked Queen again for the mention that there’s a little Joan Crawford in her too!

The exhibition, with its many wonders of art from around the world and those exclusively on loan direct from Disney’s own Animation Research Library, sounded too good to miss, especially since Paris is now just one short(ish!) train journey away from London these days. Although I was born to French speaking parents, I have not kept the language up and so, dragging my Mother along to act as my Parisian guide and emergency translator, I hopped on the EuroStar bound for the French capital. I was lucky enough to have secured an interview with curator Girveau, which quickly turned from being a formal discussion into a personalized guided tour as we chatted enthusiastically about the exhibition and our own favorite works.

Bruno has fought long and hard to stage the show, coming up against the highbrow French art critics who were initially horrified to hear that, in the place which usually hangs works by Poussin and Chardin on the walls, he planned to excerpt Mickey Mouse clips! On meeting the man himself, it’s clear that he’s an art historian with a modern edge: the leather jacket an expression of his rebellious nature and the warm smile revealing more than a hint of impish mischievousness. I had taken a full tour of the exhibition the previous day, which I was more than glad of as we sped through the enormous amount of artefacts on show. As we meet, Girveau asks me if I enjoyed and had time to see the exhibition beforehand and I have to admit that, yes, “we came at half past ten in the morning and we left at eight in the evening!”

Bruno Girveau: So you have a good idea of the exhibition!

Animated Views: Yes! What was the trigger that set you off on this road to putting the exhibition together?

BG: Ahh. Actually I had the idea of the exhibition ten years ago when I was looking at the Disney movies, the Disney classics, Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, and so on, and when I saw, for instance, the castle in Sleeping Beauty. As a historian of architecture I recognized that there were some sources of inspiration, with medieval engravings, and paintings, and castles by Viollet-le-Duc for Ludwig II of Bavaria, and so, at that moment I had the idea to do the exhibition. In fact, I’ve been at work really for three or four years; it took about three years to actually organize the exhibition.

AV: Is this something you always wanted to achieve or was it something only inspired itself from that time you saw those classics, when you said “oh I really have to do this”?

BG: It’s when I saw the classics. I said that I should do this and then I had to do a lot of research after! I read the book by Robin Allan, you may know it, which is the “Bible”; the basis of the exhibition.

AV: That’s the European book?

BG: Yes, that’s about the European sources of inspiration. It’s the best – and the only – book ever written on this subject. So I met Robin Allan a lot of times and he wrote an essay in our catalogue which is a kind of a summary of his book, which has never been translated into French. So that was the basis, and afterwards I did more research in the Disney Archives, and by meeting the artists from the Disney Studios, and so on.

AV: Was there a particular image, for example when you were watching Sleeping Beauty, that really grabbed your attention and made you sit up and take notice? “Ahh, that looks like such and such”…

BG: Yes, yes. For instance, when I saw the castle, I said to myself that it was inspired by the illuminated paintings of Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, which is one of the most famous manuscripts of medieval times, which is out in Chantilly. Unfortunately it’s not possible to loan this piece, but also there are other sources of inspiration like Gothic restoration by the French architect Viollet-le-Duc in the Nineteenth Century, and I think that the most important source are the castles of Ludwig II of Bavaria. So I recognized these kinds of very long towers in the castle of Ludwig II, which are incredible castles almost in the Disney style before Disney’s style! So at this moment I said to myself there’s something to be done, and then I realized that there is a real possibility of doing an exhibition, because there’s not only the castles, but all the cinema of Walt Disney is made of these sources of inspiration and, of course, of his own inspiration, in his own style, but it’s done with pieces from the past.

AV: It’s all melded together and they came up with something new. It must have been a very exciting time, once you saw this connection, and then it sort of exploded…

BG: Yes, because I didn’t realize that there was this connection with movies, and some are unexpected, like the German Expressionist cinema; it’s incredible to see how many connections there are between movies by Murnau, by Fritz Lang, and the shorts and the feature animation movies by Walt Disney. It’s really incredible and it was a surprise for me too. But Robin Allan found a lot of these connections in his book.

AV: It’s a wonderful book.

BG: Yes, it’s wonderful; it’s Walt Disney And Europe.

AV: So why is now the right time to present the show? With everything turned CGI it seems to me to be a healthy reminder of the kinds of films we rarely see nowadays, the traditional hand-drawn features, even from Disney themselves. Was it because it just took so long to mount?

BG: Yes, because I think it was impossible, especially in France, to do such an exhibition, about a man who is for the French the baton of mass culture. I’d say he was very pejorative. So, I’ve been waiting a long time to do it; now I think it’s possible, there are some critics, but not too many as expected, and people finally realize that Walt Disney is a great artist. So I think we had to wait to present it, in France I mean, because for many people Disney was already a genius, so it’s really only for the critics to understand, and the people like…me! I mean, I’m a curator of a French national museum, so in my world where I’m living and working…

AV: You shouldn’t like “cartoons”!

BG: Yes! But I’ve been loving cartoons for many, many years, because I was myself interested in the comic strips, and in my mind there’s no two sides of culture, there is only culture: popular and scholar…

AV: Academic?

BG: Academic, yes. That’s because the Grand Palais is the most important place for exhibition in France, but for academic exhibitions, like Poussin, Manet…

AV: Like in England, in Piccadilly, the Royal Academy.

BG: Yes…it’s the “temple”, the highest place. But to convince people from The Walt Disney Company, I said to myself that “I have to be in this place”, not another. It could have been the Centre Pompidou maybe, but this is one of the most well-known, respected places, prestigious… But, it took a long time to convince people from my world.

AV: And what has the reaction been from those critics?

BG: Ahh, I mean 90% are absolutely surprised, pleased, they love the exhibition, but there’s you know…

AV: A tiny amount…

BG: Yes, for instance, some newspapers, like Libération, “hate” the exhibition, but not because it’s “Walt Disney” but because it’s the Walt Disney Company.

AV: Because it’s “corporate”?

BG: Yes.

AV: But surely that’s what’s nice is this is about early Walt Disney; it is Walt Disney, not the Disney Company…

BG: Yes, that’s what I’m trying to explain, but some people have…

AV: Tunnel vision.

BG: Yes, they couldn’t see this without the politics; not to the artist, not to the films. So it’s difficult for them to forget all that ideology and see Disney as an artist. But it’s really 300 people against those few critics!

The exhibition opens with an introduction to Disney’s world of fairytales and their European sources of inspiration, highlighted by Philippe Rousseau’s 1885 painting Le Rat qui s’est retiré du monde (The Rat Who Withdrew From The World), which clearly evokes the feel of a classic Disney tale in its one image. On show within this section is original Disney merchandise from the time, including Mickey and Minnie figures that still draw gasps of recognition from the younger members of the public who visit. On the wall, biographies for the primary artists whose work will be touched upon throughout the exhibition are displayed, alongside what is clearly intended as a way to “tie” Walt Disney to France directly: an image of Walt accepting the French Legion Of Honor medal in 1935 is presented right next to that very medal itself, on loan from Walt’s daughter Diane.

AV: I think that the Medal Of Honor is a nice way to tie Walt Disney and the French together to start off the exhibition. Was that the intention of that, to kind of bridge a link?

BG: It’s because Walt Disney loved Europe, especially France and he came here a lot of times. The first time was during the First World War…

AV: When he was an ambulance driver.

PIONEER ARTISTS OF THE DISNEY STUDIOS

On the opposite wall, I am astonished to see Ub Iwerks’ ACTUAL drawings for Plane Crazy and Gallopin’ Goucho, and spend some time examining the nearly 100 year old images; the indentation of the pencil lines really expressing the vitality and energy that the pioneering Ub was eventually well known for. Next to these, Cy Young’s image for Mickey, in his first color appearance for The Band Concert, is interesting also for the fact that these pencil drawings are in color too. Another mouse is depicted in Art Babbitt’s pencil drawing for The Country Cousin, and standing so close to it shows the amazing amount of detail that even the shorts received; it easily beats today’s somewhat rushed and formulaic work. On the other hand, however, Babbitt’s 1930s model for Mickey feels surprisingly “off model”. I speak to Bruno about the amazing experience of being able to look at these pieces in close up, and the remarkable attitude of Disney’s own Animation Research Library, who have previously flatly refused any requests of loaning their history out to third parties.

BG: Yes, they are used to being very, very protective, but for this exhibition…

AV: They trusted you.

BG: They trusted me, I don’t know why! Maybe my plan was good, but they’ve opened the doors of the archives. They’ve never before lent so many pieces, but they loved the idea of the exhibition, and I went three times to the Animation Research Library in Glendale. You know, it’s a long way to get such pieces, but they were really very enthusiastic, and so it was a pleasure. I think it’s the first time that they agreed to lend so many pieces and items like the first drawing for Mickey. But we have also lent from Diane Disney Miller, Walt Disney’s daughter. She was very generous, and she understood the plan.

AV: A very switched on lady. I interviewed her in 2001 and she was lovely.

BG: Yes, I think so.

AV: Now, this Ub Iwerks stuff is just, for me, mind-blowing. It’s just overwhelming, and what’s really superb to see is the indentation on the paper; you can just really see that energy and imagine what it was like for them back then when they were just making their first films in secret and showing them in the garage, and it’s fantastic…

BG: Yes, It’s the very beginning of the Walt Disney story.

AV: And who would think…what would they think now if they saw it! It’s here, you know?

BG: Ahhhh…

AV: For them at the time it was just a quickly drawn image and…whoosh…on to the next one.

BG: Yes, but really it’s a nice piece of history; it’s how he was formed.

AV: Oh, absolutely.

The introductory room suitably covered and drooled over, we begin our tour proper, and my excited and insatiable inner thoughts of what wonders we might bump into next are answered quickly by perhaps the most breathtaking exhibit in the entire show, and something I was totally unprepared to witness: the Snow White Oscar, presented to Walt by Shirley Temple in 1939 for the creation of the world’s first animated feature, and consisting of one full-sized Academy Award and, naturally, seven miniature ones. Not for the last time as I walk the halls of the Grand Palais, I am speechless.

AV: This is…amazing.

BG: Lent by Diane Disney Miller. It’s a very moving piece.

AV: Yes, I saw this yesterday and I spent about half an hour just looking at every angle. It’s, I think, the only distinctive special Oscar that’s ever been made…

BG: Of this kind, yes, and you know it’s so different from the others because Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs was the first feature animated movie ever done. So they had to imagine another kind of Oscar for it. It’s not only amusing, but it’s about what Snow White being the first movie means.

AV: That’s fantastic. I’m just speechless.

The Snow White Oscar leads us through a projection room that highlights several film clips that influenced the Disney films of the time. The Mad Doctor is juxtaposed with a scene from Frankenstein, while the King Kong parody in The Pet Store will be known to many fans. Walt was a known Chaplin fan, and scenes compared between the Donald Duck short Modern Inventions and Chaplin’s Modern Times show up the similarities in both of their work. The clear stimulation of German Expressionist cinema as Faust, Waxworks, The Cabinet Of Dr Caligari and Der Golem are portrayed in accompanying clips from Fantasia and The Sorcerer’s Apprentice – truly insightful once one appreciates what the Studio artists were themselves watching.

The section is very popular, with the limited seating packed to standing room only, and we have a little difficulty in getting through. Finally, there’s a break in the crowd, we make a run for it, and I’m able to question Bruno on another, this time non-intended moment of astonishment.

AV: Moving through these clips, I was surprised to see The Mad Doctor was…colorized! Was that deliberate or simply what was provided?

BG: Yes, it’s not the right version! Unfortunately, the Disney Company gave us this copy, but it should be in black and white.

AV: It should be black and white, yes. I only noticed it quickly because it’s actually one of my absolute favorite Mickey cartoons and I know it very well, from when I was able to get hold of an old print years ago before it was re-issued on LaserDisc and DVD. The scenes at the end, where he’s walking in that spooky castle, and there are those 3D backgrounds – in 1933 no less – that’s, you know, that’s fantastic.

BG: It is, and there’s a lot of connection with Frankenstein, by James Whale.

AV: Yes, another favorite film of mine. And in Disney you see the James Whale films and Universal’s Old Dark House…all of that. You were saying that you found it surprising that they were borrowing from those figures, Murnau’s Faust for example, and those kinds of films. How did you put the sources together when you started looking for them?

BG: Some of these connections had been found by Mr Allan, some others by me, and I’ve asked cinema historians. So this is a mix of all these people, but I’ve seen the Disney movies a lot of times too, and found the sources of inspiration in my own culture. As I knew that the German Expressionist cinema was one of the most important of inspirations, I saw all the German Expressionist films to see the connections between them, and especially for Fantasia, the Night On Bald Mountain.

AV: That scene where all the demons are rising up from the town is almost shot for shot.

BG: Yes it’s directly inspired by Faust, by Friedrich’s film, of 1926.

AV: I have all those on DVD too and I’ve always found them fascinating, almost animated in themselves and certainly with style that is, I would say, theatrical even.

BG: Yes, and I am sure that we can find other such examples of inspiration.

AV: As you say, though, it is strange to think that you’ve got these “Mickey Mouse” artists watching these films.

BG: Yes!

AV: …at Disney’s of all places!

BG: Yeah, but Walt Disney said to his artists that he wanted them to see those movies, not only the German Expressionist movies but also films by George Cukor, and by Chaplin, by Keaton and so on. All the Hollywood cinema, and the European cinema.

AV: And then Disney was accepted by Hollywood itself, and he became one of the big players himself, especially after Snow White of course, when just before that everybody thought he would fail, and that would be the end of Disney’s.

BG: Yes, because he’d tried to work in the cinema industry, but he didn’t manage to break in, so he decided in this moment that he would become the master of animation, and he managed to do animation as high art, so it’s really amazing.

AV: I guess it worked out for him!

Breaking away from the endlessly repeating Steamboat Willie whistle from the film sequences, we enter the book room, where a more sombre tone of some reverence seems to hush the excitement of the exhibition down. Perhaps it’s the ingrained act of remaining silent in a library, but the enthusiasm is barely contained once my eyes catch the selection of Walt’s own reading matter as well as some picks from his 1935 tour of Europe that litter the room alongside illustrations by some of the world’s most renowned and celebrated artists, including Gustave Doré, Edmund Dulac, Honoré Daumier and Arthur Rackham. These are Walt’s original copies of these books, and it’s of great interest to notice a couple of Snow Whites, books on Peter Pan and Alice In Wonderland, and a collection by Charles Perrault from 1697.

The staff library was set up for the benefit of the artists, who were allowed to borrow the books and keep them for any given length of time, and Walt kept the library – now stored at Walt Disney Imagineering – well stocked. A 1949 trip around the world resulted in 90 books being sent from France, 81 from Britain, 15 from Italy and, reflecting just how great an inspiration the German illustrators were from that country, 149 from Germany. On loan from WDI, it’s fun to pick out the names of those artists that borrowed the books from the Studio library – from the card inside, we know that Dick Huemer returned Grandville’s Fables on Sept 22 1955!

The room wouldn’t be complete without mentioning Gustaf Tenggren’s Pinocchio drawings; Eyvind Earle’s Sleeping Beauty, and a 1923 book, Madame D’Aulnoy’s Fairy Tales, illustrated by Tenggren himself before he was lured to the Disney Studio to work on concepts for Snow White. Images from those later films adorn the walls to illustrate further the obvious visual connections between the sources and the final product, as “Disneyfied” by Walt. Claude Coats’ original oil on paper rendering of Mickey Mouse as The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, which was lithographed for the Fantasia LaserDisc box in 1990, can be viewed with all the touches of human hand inherent, and when we come to some Snow White concepts, it is just spine chilling to be able to lean in to the actual drawings that we only usually get to peek at via the still galleries on those kind of videodisc collections.

Some of the titles of the books will be mythical volumes long since known and perhaps even peeked at by many fans, but astounding to see “on the page”, as it were. Eadweard Muybridge’s Animals In Motion sits under glass for close inspection alongside his The Human Figure In Motion – BOTH SIGNED by the author! And if that wasn’t enough, Edwin George Lutz’s Animated Cartoons, from 1920, is right next to them, with Charlie Bowers’ Aesop’s Fables, from 1923 appearing with a very “Walt like” signature version of his name on the cover, perhaps itself its own sort of source of inspiration.

A final touch is the appearance of another animation pioneer’s work, that of Winsor McCay and a sequence from his 1911 Gertie The Dinosaur, which evidently still has the power to grip both grandparents and grandchildren alike as they thrill to Gertie’s exploits again, or perhaps for the very first time. Gertie, it seems, is still awe-inspiring kids of today.

AV: Apart from the film clips, some of the artists themselves have acknowledged the painters and illustrators they admired. At other times the sources seem perhaps more sketchy. There must have been some educated guesswork used in placing some of the inspirations, and especially with these books. What else was involved in pulling the artwork together that inspired Disney and his artists?

BG: Oh yeah, there was a lot. One of the curators of the exhibition is Pierre Lambert, who is one of the most famous writer historians…

AV: Ahh yes, of those amazing books.

BG: Yeah, he put together a lot of really amazing books, and he met a lot of artists before they died and he managed to ask them about the kind of sources of inspiration. He also had the idea of doing an exhibition one day, and I met him four years ago. I’ve spoken myself to some of them…people like Joe Grant; before he died last year I met him two or three years ago, and I talked with him for a very long time, and I asked him what his sources of inspiration were, for instance, for the Queen and the Witch in Snow White. He said to me, “yes, it’s a mix of Doctor Jekyll And Mr Hyde, there is a version with John Barrymore in 1920”, and I said to him, “did you see the version by Mamoulian in the ’30s?”; “yes, but it’s not the only source of inspiration, it’s also a woman who was living next to me in another house, and it’s also Joan Crawford…” So, I had some conversations with some artists. Some of them have, in fact, written what their sources of inspiration were, so it’s the mix of all those things, but also there is Robin Allan, and I did some researching in the Disney Archives to know, for instance, we are in the room devoted to the books, of literary sources, and so we could find in the register book, in which all the books are listed, we can know exactly when they bought all the books in the library. All the books which are in this room were the ones bought in ’35 by Walt Disney himself, so it’s just another way to know where the sources of inspiration are. Because we have books by Grandville, by Doré, by Daumier, but also by German illustrators like Moritz von Schwind, Richter, Busch; also by English illustrators, of course, like Rackham, and so we can find the connection between the books and the illustrations of the books and the movies.

AV: Especially in the Disney library, where they had to date and sign for each book, so that would tie in to what films they were working on as well.

BG: Yes, we made the connection between the date in the books where they were listed and the dates of when the films were released, so for instance, for Sleeping Beauty I’ve seen that Eyvind Earle, who is one of the most important artists for the film, took out books about medieval gardens, about medieval architecture, Gothic architecture in France, a book by Viollet-le-Duc, so it’s really easy to find…

AV: It’s another way to tie it together. Speaking of those illustrators, I must say that Tenggren has always been a favorite of mine…

BG: Yes.

AV: …and then to see an original book that he illustrated was very special.

BG: Yes, and it’s the reason why Walt Disney employed Tenggren, because he had seen the books illustrated by Tenggren in the very beginning of his stay in the United States, and Disney found them absolutely amazing, tremendous, so he appointed Gustaf Tenggren in ’36, during the conception of Snow White and, yes, obviously Tenggren is one of the best.

AV: I remember seeing his image of the Seven Dwarfs when I was very young and even at that age the image just speaks to you, doesn’t it? The whole character comes to life within the picture; he just gets all that perfectly on the paper.

BG: He came from Sweden, and was of course inspired by the trolls, and the dwarfs in Scandinavia in his work. It was all, of course, completely transformed by Disney, but it came from Scandinavia, via Tenggren and his culture, brought back from Europe.

AV: And there’s clearly a lot of that influence in Snow White. It must have been tough going through and choosing which books would actually be seen. What was the process of selection?

BG: Oh, it’s a selection from French, Italian, German and English books, and most importantly, the artists. We know that the masters inspiring Disney were Gustave Doré, Honoré Daumier, Ludwig Richter in Germany, and Hermann Vogel, Arthur Rackham in England and Beatrix Potter of course. So we have focused on these books, but there are thousands of books in the Studio library…it was really books lent by artists from the Studios, and that were on their tables when they drew.

AV: That’s remarkable.

BG: And we have an example of a book lent by Walt Disney himself, and we opened it at the page…did you see?

AV: Yes!

BG: You have the card inside…and the first name is Walt Disney!

AV: And then Dick Huemer…

BG: It’s Les Fables de La Fontaine de Grandville. It’s quite a big deal, for the French I mean…a lot of people realize today that Disney was reading Les Fables de La Fontaine, illustrated by Grandville, a French book, from the 19th Century.

AV: As with everything here, it’s amazing how this is as open as it is to people that wouldn’t have had access or realized any of this before.

BG: Yes, it’s also to say that we’re not so different. American people and European are not so different, because Walt Disney was not a cultivated man, he was a middle-class American, I could say without any culture, but he had a fantastic, tremendous imagination and he had the idea to look at European culture; to read books; to see some movies…so he was interested in culture, even if he didn’t want to say that he was. He was afraid of being an artist.

AV: And perhaps maybe being accused of “copying”.

BG: Yeah, but it’s absolutely wrong to think that! He was beyond the others…

AV: An extension of what came before.

BG: Yes, and as a great artist he managed to create his own universe; his own world absolutely different from his sources of inspiration; completely new. I mean Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs was the first film ever made like that! So, we can’t say that it’s a copy of “this” or “that”.

AV: Although lots of people would like to say that, I think. Some people at the time, especially, which is maybe why it was so difficult for him to be accepted, because he was so different.

BG: Yes, he was different. That’s right.

AV: What’s so appealing is that all ages are able to come and enjoy the exhibition. We toured with the audio description yesterday and saw, although it’s not Disney…

BG: Winsor McCay and Gertie The Dinosaur…

AV: Yeah, and you see the grandparents listening to the guide and then getting excited themselves about telling their grandchildren all about how things were animated. It brought to mind that all of the art here holds universal appeal, and I just think it’s wonderful that children are still thrilled to be watching this.

BG: Yes, and you know it’s a short released in 1914!

AV: My favorite of his is The Sinking Of The Lusitania, which is phenomenal.

BG: Well, he was one of the masters of animation. Very modern.

AV: Absolutely! And there are shots in there that are much more powerful to all that the special effects of Titanic – which borrowed, I think, a lot from that film – tried to achieve emotionally.

BG: It’s incredibly modern, that’s the reason why the people are so attracted.

AV: Yes, and I was pointing out yesterday how this was even before they had cels, and McCay recreated every background as well. I mean, you see all the detail and then when the water sinks…it really is just exceptional.

BG: Well, I would like to do, one day, an exhibition about animation from the very beginnings to the manga we have now.

AV: Wow!

I continue to talk with Monsieur Girveau as we begin to stroll down the walkway between the book room and the next section. A huge panoramic blow-up of Snow White looms over the visitors as they walk through, and Girveau points out a quote by Walt, “I believe in fairytales”, which I agree is a great point of view. We continue through into the Architecture sections, which shed light on the many real world structures and locations that the Disney artists drew from, including in some cases their original European countries of birth. Many of the acknowledged artists in Il était une fois, Walt Disney are known to have European backgrounds, most notably Tenggren, of course, but also Albert Hurter, from Switzerland, and the Danish Kay Neilsen.

As one compares the resulting Disney images with the inspirations, these influences are clear – in some cases one could easily mistake an original source as a concept image for any certain production, perhaps as with the town in Pinocchio, modelled on Rothenburg in Bavaria as seen in Arthur Wasse’s Vue de Rothenburg. Tenggren pops up again here, bringing with him his German influences that would greatly affect Snow White and the spectacular Pinocchio concepts on show. It was Tenggren’s idea, Bruno shortly tells me, to transpose Pinocchio’s setting from Italy to Bavaria. At this point the remarkable scope of Girveau’s whole enterprise dawns on me, also partly due to the fact that I now find myself staring ardently at the ORIGINAL background art for the outstanding opening shot of Pinocchio, where the frame starts out in the stars over a small town and the Multiplane Camera pans past the rooftops, down into the street and up to Geppetto’s cottage. As the scene plays overhead on a projection screen, I wonder where else in the world could you watch this famous shot and then turn around to view that original hand painted artwork up close? Astounding!

The section is completed with the pick of Eyvind Earle’s obscenely detailed (preliminary study!) panoramics for Sleeping Beauty, based primarily on the paintings of Christian Jank. These drawings and paintings, justly celebrated by fans and historians of animation art, are fascinating to view up close, and one could easily spend the entire day in this one section alone, just picking out all the details. I admit to Girveau that the opening Pinocchio shot background has me hooked…

AV: Walking through here yesterday, I actually became very overwhelmed by just the amount of art on show, and I’m glad I’m back today because when we’re finished I’ll take another tour. I find that you can’t take it all in; there’s just so much that you simply want to stand and stare at. I want to absorb it all, and remember it.

BG: Yeah, but many of the drawings, the Disney Studio drawings are masterpieces of drawing.

AV: This one, of Pinocchio’s town…I’ve seen this image reproduced, of course.

BG: This one is one of my favorites…

AV: Yeah, I have to say it’s probably one of my favorites here. To see this up close and be able to make out those brush strokes…

BG: And this is really the background production painting for the first sequence of Pinocchio.

AV: From the beginning, yeah. Actually, I think again we were here for about half an hour and I was just pouring over it…

BG: Yes, for people who know animation and Disney scenes, it’s a great opportunity to see these kinds of things.

AV: Phenomenal.

BG: The first time I saw it in the Archives I spent half an hour in front of the piece, saying to myself “Wow, it’s incredible”.

AV: Yes, yesterday we were here doing the same. And you can’t help but do the pan and try and track it…

BG: You can imagine the Multiplane Camera…

AV: Also the town concepts themselves, based on Rothenburg, are highlights. All of Tenggren’s work over on this side is simply breathtaking.

BG: The watercolors by Tenggren are absolutely wonderful, and Tenggren actually was the man who moved Pinocchio’s story from Italy to Bavaria, because he was an artist from the north of Europe, with his own ideas and culture. Walt Disney, at the very beginning, didn’t want to move the story from Italy, but when he saw the watercolors by Tenggren…

AV: How could he say no?

BG: Yes, yes! Obviously you’d say yes; it’s the right idea.

AV: You’ve actually answered one of my next questions, which was going to ask about your favourite piece here. It’s clear you’re in love with the Pinocchio town as much as I am!

BG: Why? Because it looks like a Bruegel painting, it looks like primitive painting. Very, very liberated. It’s a wonderful piece, and we can possibly forget about all the sources of inspiration. Of course, just above the background we have a Bruegel painting. It’s very, very important, but they’re not so far apart.

AV: And we have this remarkable work for Sleeping Beauty.

BG: Yes, the gouache by Eyvind Earle for the fairies’ house in the forest, and it’s absolutely amazing, technically superb. It’s wonderful.

AV: Again, you could spend a day looking at all the detail, and then look at it again and still find something new.

BG: And all these drawings for the forest in Sleeping Beauty on the other wall are background production drawings; I mean the ones used for the shooting of the sequence.

AV: There is a feeling that you could stare and stare and something is going to almost “move”, like you’re waiting for something to happen because they’re so full of life. What came to mind yesterday is that we have these important paintings, works of art which are there for their own sake, to look at and to take in, but all these animation backgrounds…they have the same level of detail, and yet they’re just there to just get passed over once, and they’re gone. Back when they were making them there was no video, DVD, or television even, and these images would potentially never be seen again. It’s just amazing that all this detail goes into it for what was essentially “swoosh” and it’s gone.

BG: Yes, it’s only a few seconds in the movie. I compare my exhibition to…in French it’s “arrêt-sur-image”.

AV: Like a freeze-frame. You can pause it.

BG: Yes, it’s a way to spend more time on one image of the movie, and this is the opportunity to see the background as long as you want.

AV: Yeah, because you see these on the LaserDiscs and the DVDs, they have the galleries, but that’s still not the same as coming here and looking and, as with the Ub Iwerks images earlier, you know that his pencil was on that paper, and you know that Eyvind Earle was drawing this piece, and actually painted that, and it just takes it to another level.

BG: Yes, yes, because you are really in front of the art.

AV: Like with this Peter Pan one…

BG: This one was for the overview of London for Peter Pan, and it’s compared to a watercolor by Gustave Doré, La Nuit de Noël (Christmas Night).

AV: Yes, you can certainly see the identical colors, and the lines, you know, and the whole same feel of it…

BG: Yeah, but it took a long time to find the right comparisons…absolutely clear and evident; obvious for everybody.

AV: The choices are…we say “spot on” in English.

BG: Yes, spot on.

AV: Now, why just Disney? The other studios at the time often included similar artistic references, perhaps Max Fleischer especially, and there were a lot of artists running between the studios, such as Grim Natwick, who did Betty Boop at Fleischer’s and moved to Disney and was put to work on creating Snow White because he was “good with girls”. Did you keep it tied to the Disney Studios because of the name and the vast amount of work produced?

BG: Yes, I think that Disney was the most popular, so it was that everybody knew or has seen Disney’s feature animated movies, but the exhibition for me is not only an exhibition about Walt Disney; it’s also about the links between low art and high art, and I think that Disney was the most relevant, or the best example to explain the links between those two worlds. So of course we could do this demonstration with all the studios, but I think Disney himself and all the artists around Disney, who came from Europe…Kay Nielsen, Gustaf Tenggren, Albert Hurter…there are so many great artists in the Disney Studio that I just think that these Studios were better.

AV: Well, Walt was always pushing for that as well, wasn’t he, in that direction, whereas Warner Brothers was very broad, big characterisations, and Fleischer’s was possibly “crude”, with the rubber hose type of animation.

BG: Yes, it’s quite interesting, of course, for people who love animation, but I had to choose one point of view, and the most efficient, especially for such a place. But I have in mind something more complex and more exhaustive.

AV: The next one, the sequel!

BG: Yes!

AV: Was it therefore easier to concentrate on one Studio, or because it was Disney and they’re so big was it still just as hard as putting a show on from various different studios?

BG: Yes, but I hope that one day I can do an exhibition about the history of animation, and Disney will be just a small part…because there are so many other things.

AV: That’s going to be a nightmare! I’m just thinking of where all the copyrights for all the cartoons have now spread everywhere.

BG: Yes, it’s really quite difficult to do such an exhibition…for all the rights, especially for movies. For all the movies in this exhibition, to have the clips – phew! It’s a huge task.

AV: You can see what’s gone into this…it’s absolutely amazing. Leading off from that, when you were putting this all together, was it always just about Disney, or were there times when you were tempted to bring some other names in and maybe open it up to other animation intellectuals such as Chuck Jones or, maybe, Tex Avery as well? Or, in concentrating on Disney, was there a line drawn at what you could include, or not include? How did you come to the selection of saying “okay, we’re going to focus on these films and leave those ones out”?

BG: No, I always focused on Disney. The first idea was the sources of inspiration. So I imagined with this that there should be links between the sources of inspiration and Disney movies, though you’re right, some of the movies are not in the exhibition. For instance, The Sword In The Stone…previously I had some drawings in this section of the exhibition about architectural drawings, but I had too many, too many drawings, so I didn’t put these drawings in, and some films, for instance Lady And The Tramp there are only two or three drawings; One Hundred And One Dalmatians, two.

AV: It’s more about what’s directly relevant…

BG: Yes, in terms of inspiration. But sometimes I was tempted to include some drawings only for their own beauty…

AV: Art for art’s sake.

BG: Yes, but it was so difficult to make the selection, because I had about 400 drawings that we were bringing, and that’s only for the Disney side, because we’ve also all the paintings and sculptures from western art, so it’s just half of the exhibition. I had probably more than 400, and I had to go back to 250, so you can imagine how many drawings…

AV: So it was a case of “oh let’s sneak this in…”, but not too many!

BG: You know there are other things involved in such an exhibition as well; I mean the cost of the exhibition. So when you say “it’s a huge exhibition”, it’s almost 500 pieces, so even for the Grand Palais it’s…

AV: It’s a big one!

BG: Yes, it’s a big one. I heard it cost about three million Euros, so even for the Réunion des Musées Nationaux it’s…big.

AV: So the criterion has to be focused.

BG: Yeah, I have to focus it on many points and other issues.

AV: So, this piece here, of the European Disney castle, is the only modern piece in the exhibition, I think?

BG: Yes, it’s the modern one. It was made for Disneyland Paris. I was expecting another model, the first model made for the first Disneyland in Anaheim, California, more ancient than the one made in 1955. Unfortunately I didn’t manage to get it, so I have this one, but it gives an idea of the castle in three dimensions.

AV: What I like about this is that it’s almost like a regurgitation of all the influences. You have the original sources, and then you’ve got the Disney castle from ’55, the DisneyWorld one from 1971, and then the Sleeping Beauty one that they use as the Studio logo, and all of that is mixed in and you get this one which is perhaps the ultimate! So it’s like a whole big full circle, this being so much more intricate than the 1955 one, with it having everything extra on it. Kind of like the quintessential fairytale castle.

BG: Yes, right. Absolutely.

AV: So, it’s quite a nice piece to have. The old one would have been great, but this is a good substitute.

BG: Yeah, and there is something there from the early drawings by Eyvind Earle…

AV: The trees…

BG: The square trees. The shapes for them are all squared because it’s inspired by primitive painters, Flemish and Italian primitive painters.

AV: And his tall barks…

BG: Yes, there as well.

AV: And are they like that? At the park? Or was it just for the model?

BG: Ahhh, I don’t know! I’ll have to check that.

AV: It would be interesting to see if they carried that through.

BG: Yes, and behind the castle we have all the sources of inspiration by Viollet-le-Duc, the castle by Ludwig II of Bavaria, and the fantastic drawings by Eyvind Earle. He used to say that nature shouldn’t be drawn as realistic…

AV: Nature shouldn’t be natural.

BG: Yes, as did the primitive painters.

AV: And he used a kind of stencil to add the leaves on.

BG: Yes, there are a lot of pictures of Eyvind Earle working.

AV: Yeah, and again the comparisons are just spot on, and they’re such a good choice for people coming to this for the fist time to be able to see this and easily pick out and recognize, “oh yeah, that’s that” and “that’s this”.

BG: Yes, and this exhibition is also about the history of the moving of the imagery. From the “old world”, going to the United States, and coming back to Europe, completely transformed by Disney…it’s surreal. But, we are not always able to understand that, so this is the opportunity to say “look at these images”. Everybody knows the castle, of Sleeping Beauty, but do you know that it came from this?

AV: Exactly, and there’s the castle in The Sword In The Stone, where Merlin lives at the top, which always brings to mind to me the notion that if the Sleeping Beauty castle had been ruined it would have looked like that. They seemed to have gone for that look, I think, in the film, because it’s all falling apart, all the bricks as Merlin walks up the stairs fall and the tower shakes and rumbles. Was there an inspiration for that type of castle there or were they, as I think in this case, referencing themselves? It always gives the impression to me that they were looking at their quintessential castle and ruining that, maybe as a comment on switching from the lush, 1950s cel-painted look of Sleeping Beauty and going to the rougher, sketchy look of the 1960s Xerox process. Is this Disney borrowing from Disney?

BG: Yes, sometimes the source of inspiration came from Disney. I mean, for Fantasia, we’ve a short, from the ’30s…

AV: Water Babies.

BG: Yes, and all the Silly Symphonies were a kind of laboratory for the next feature movie, so it’s not a surprise.

The Architecture section flows through into Anthropomorphism, which looks in detail at Disney’s unending practice of giving human attributes to otherwise dumb animals or inanimate objects. Chief among this section is the chance to get up close and personal with Jiminy Cricket, pre-and-post donkey incarnations of Lampwick from Pinocchio, and the Nutcracker animals of Fantasia – all in the form of beautifully detailed maquettes that haven’t been seen publicly in years.

A favorite of mine within this selection is Emmanuel Frémiet’s striking bronze Ours mendiant (Begging Bear), portraying a docile and contemplative bear reaching out with a friendly paw. Though it does not seem to have a direct influence on any of the films touched upon in Il était une fois, Walt Disney, the anthropomorphism is a clear indication of the variety that would pepper Disney’s films and continue to do so as recently as Brother Bear, to use a blatant example. As with the rest of the exhibition, this section is packed with visitors, the mixture of humanized animals from both an artistic heritage and Disney proving to be a big draw. I ask Girveau if the turnout for the exhibition has been better than expected.

BG: It’s completely different from the usual attendance, with lots of new people. There are a lot of parents, and as you say, grandparents and children. I think it’s the first time you can see children in an exhibition at the Grand Palais. People are concentrating on the Wednesday, which is the day when school is closed here, and on the weekends, but there are a lot of people, and during the holidays it increases. But at the opening of the exhibition people who were used to coming to the Grand Palais, they were, how could I say…

AV: Shocked?

BG: Shocked, yeah, well not shocked but they thought that it was not an exhibition for them. But they’re beginning to come back because they have heard that it is an exhibition put together by a historian of art, and it’s not only a Disney exhibition. In a way it’s an academic kind of exhibition, because there are some paintings by well known artists, but also drawings by Disney artists. And those pieces are, according to me, real masterpieces.

AV: Oh absolutely, of a different kind.

BG: Yeah, of a different kind.

AV: And absolutely as valid.

BG: Yes, but you know that a curator told me that you couldn’t hang a painting by Bruegel and a Disney drawing; it’s not art…

AV: You have proved it can be done.

BG: But just to say too, that it’s not so easy in the curator world to do such exhibitions.

AV: I find that odd, because art comes from art, which you demonstrate at the end of the exhibition, for example. But for somebody who is in that environment, in that world, not to see that…

BG: Actually, I also had some unexpected congratulations, for instance, by Pierre Rosenberg, who was the former director of the Louvre, which is very well known…

AV: It’s an institution.

BG: He is an academician too, the most well known French curator in the world, and he’s absolutely in love too…

AV: Astounded.

BG: Yes, and he’s a man of the Chardin Exhibition, he did about 40 exhibitions here, and he came back two or three times, as a grandfather with his children, so it’s really unexpected, but I’m really happy. You may change minds.

AV: Well that’s what you set out to do, so you’ve succeeded. But it’s a good introduction for children to the world of art as well.

BG: Yes, really.

AV: Ulterior motives?

BG: Yes, it’s a new kind of exhibition for a new kind of audience. And maybe some of these children may learn something about art.

AV: Yesterday, we saw children drawing the Pinocchio maquettes, and one of them was studying it, drawing it, and you know, perhaps there’s an animator for the future. But what’s really nice about this art is that it touches everybody. You look at it, and even just seeing a background launches this internal recognition, not even as someone who knows animation like myself, but the faces on all the kids. They smile, and it’s like these pieces where they look and recognise them, but then they’ll see that again back in the originals and start to recognise the inspirations.

BG: Yeah, and there is also something very important we didn’t talk about which is the scenography of the exhibition, which was made by one of the most famous Italian designers. His name is Alessandro Mendini, and he’s a designer for Alessi, for Swatch, Philips, us…everybody has something designed by him, and it’s the first time that he’s done an exhibition. I’m really, really happy because it’s exactly what I’ve been waiting for.

AV: The display cases look as though they have been coated in pixie-dust.

BG: Yeah, do you know the displays are inspired by the coffin of Snow White…

AV: Ahhh, yes! I didn’t know what it was, but I knew there was something…

BG: Yes, of course, it’s not a coincidence. And the plexi-showcase is inspired by the glass cover. The base is from the base of the coffin in Snow White.

The examples of anthropomorphism and the talk about Walt’s first feature bring us nicely into a devoted section on “the first and fairest of them all”. Particular attention is given to the forest escape sequence from Snow White, from the inspiration of Yan’ Dargent’s painting Les Lavandières de la nuit (circa 1861), which depicts the haunted human-grabbing hands of the forest trees, through the Studio’s concept and background art of the stunning ravine-drop layout, to playing the fully completed sequence on an overhead projector. The progression perfectly illustrates the immense power this scene still has with its sharp cuts, intense action and heart pounding music, thwarting anything the CGI pretenders have yet accomplished.

Another example of Walt’s groundbreaking genius is found in a comparison of the Wicked Queen’s transformation into the Old Witch, reminding us that Disney had perfected the art of “morphing” long before computers made it easy! This Queen/Witch transforming collection contains, as a highlight, an explanation into the genesis of the character, with Joe Grant’s original pencil sketches for the Old Witch being absolutely extraordinary, as well featuring the oft-mentioned Queen/Joan Crawford comparisons and tossing the Naumburg Uta into the mix for a fresh twist.

All of which makes spotting the sources of inspiration in the Disney Studio’s work something of a game to be played in future, especially when watching other films of the Golden Age period. One such image that demonstrates this is the balcony scene from George Cukor’s 1936 version of Romeo And Juliet, almost shot for shot staged in the same way for the similar encounter between the Prince and his one true love in Snow White the following year. Looking through the countless examples on display, it soon becomes clear that Walt and his artists were not only absorbing and retelling stories, but their own visual lineage as well, long before other more fêted artists, such as Andy Warhol, made it “okay” to do so.

And then downstairs! We’re roughly just past the half-way point now, and yet the exhibition continues to expand. Concentrating on Disney’s early animated features, we enter a series of “rooms”, each dedicated to the Studio’s first few movies following the Snow White milestone. Pinocchio features many pieces that may be familiar to aficionados, including maquettes of the entire cast, though several have never been seen before.

It’s clear from the space provided to the film that Pinocchio is something of a Girveau favorite, which I’m guessing is probably second only to his love for Sleeping Beauty. What’s especially exciting is seeing the actual Pinocchio marionettes built and used for the production, and hearing the extraordinary story behind the discovery of one of them…

AV: What is important, and nicely achieved with the inclusion of the maquettes here, is that the character designs get good consideration as well. The backgrounds, because of what they are essentially, routinely get a lot of attention and are looked on as painted works, but the show illustrates that the characters have just as much care, if not more, taken over them. What is high art’s stance on maquettes – because of their delicacy are they more significant than the model sheets or are the character design drawings just as vital?

BG: I think it’s both, because they were made to help the artists to imagine the characters in three dimensions. There are some model sheets for three dimensional drawings which help the animators, especially for Snow White, but unfortunately there’s only one model, which we have in the exhibition.

AV: I like how they have been spread throughout the sections, but this is the most concentrated collection, for Pinocchio. Monstro, for example, is incredible.

BG: For Pinocchio we have a really large range because they still exist. It’s not the case for Snow White, for Fantasia, but it was the only way to have an idea of the characters in three dimensions. And so these pieces were, like the books upstairs, on the drawing tables of the Disney artists. So, it’s very moving to see them, and especially the puppet of Pinocchio on the left which was the original puppet used for animation, for the character of Pinocchio. You know that they found him behind a wall?

AV: Behind a bookcase?

BG: Yes, completely, found three/four years ago, and the people who found them called the Disney Archives, and said “we found something”…and it was a case of “ahh, just stop everything”…and it was this puppet.

AV: That’s a miracle, to think that was all those years later.

BG: Yes, it was unbelievable.

The scope of the show has never been in doubt, but turning the corner into Fantasia’s domain and just catching a glimpse at the length of the exhibition space to come really does reiterate the fact that Girveau’s Il était une fois, Walt Disney presentation is huge. The Fantasia section looks at sources for the many mythical creatures in the film’s various sequences, including a clip from the previously mentioned Silly Symphony from 1936, Water Babies.

At this point, I mistakenly inform Bruno Girveau that “I found Water Babies an interesting choice” because it is the one Silly Symphony that wasn’t actually made by Disney. I am, of course, confusing this with Merbabies, a sequel film that Walt wasn’t too keen on completing although there was great demand for it. Rudolph Ising and Hugh Harmon used to work with Disney at his first studio in Kansas until they went off and created their own studio, Harmon-Ising. For some reason, Walt needed the Silly Symphony finished and it was outsourced to them and they actually produced it at their studio. It was developed at Disney’s and released under his name as a full Silly Symphony entry, but Harmon-Ising animated it. Since I had confused the two (very similar) films, my wondering if that slice of trivia was the reason it was specifically chosen ended up being a moot point, and something that I instantly recalled once I returned to the hotel (of course)!

Bruno politely listened and told me that he’d “learned something”, and although it could well be that he didn’t realise my mix up, the fact remains unknown by all but the most avid aficionados. The Harmon-Ising pair, whose own Symphony series the Happy Harmonies was very similar in design, did produce the follow-up Merbabies, but the Water Babies film on show at the Grand Palais is a Disney production. However, my note that the even later third film, Winkyn, Blinkyn And Nod, might have been perhaps a better choice still stands, as it has much more similarity in terms of foreshadowing Fantasia in its backgrounds and lighting.

Of the other examples on show, the paintings Dissonanz (Dissonance) and Kämpfende Faune (Fauns Fighting), both by Franz von Stuck (from 1910 and 1889, respectively) show the clear influences on The Pastoral Symphony sequence’s character designs. Heinrich Kley’s watercolors are compared with Kay Nielsen’s astonishingly striking concepts for the Night On Bald Mountain, while scenes from Benjamin Christiansen’s Häxan and FW Murnau’s Faust play against the completed Chernabog sequence – the winged and tormented figure of Emil Jannings’ Méphisto really stressing the almost pastiche nature of Bill Tytla’s celebrated character animation.

Indeed, allowing for such close viewing also belies some of the short cuts taken by the Studio in the production of the films, and surprisingly, for all its artistic aspirations, some selections from Fantasia show up the differences between the intricate concept pencil drawings and the sometimes rather more simplistic and seemingly cruder final paintings.

A full audio guide is an optional extra for both adults and children, which is an immense bonus as the show spreads its sights to educate widely, but one description erroneously points out that Fantasia was Mickey’s only starring role in a feature. Even given the focus on the first features and Walt’s own timeline, the show has forgotten that the Mouse had a much bigger role in Fun And Fancy Free, from 1946, in the Mickey And The Beanstalk sequence. I ask Bruno why some of those films have been omitted…

AV: The show obviously concentrates on Disney’s early films in particular, while the later ones have been given smaller space. How was that balance found? I was a little bit surprised to find a lack of coverage on the later 1940s work – during the War there were many striking artistic and iconic images produced by the Studio, and even in the “Package Features”, where Walt was fundamentally churning out a number of “Popular Fantasia” sequels like Make Mine Music and Melody Time, there were many stylistic sequences.

BG: Well, it’s only a choice of curator, because Fantasia for instance, is the best example for us, and some of the other sources of inspiration were not so easy to illustrate in an exhibition. An exhibition is not a book, it’s not a movie, it’s something different that means you have to have something which can work in a room, so that’s the reason why I’ve left out some films like Make Mine Music or, yeah, Fun And Fancy Free. It’s just a choice of curator. You’ve seen I can have some really good paintings for The Pastoral Symphony in Fantasia…these are the masterpieces of symbolist painting in Germany, paintings by Franz von Stuck, and an artist from Switzerland, Arnold Böcklin, they are masterpieces…and I have convinced the German museums to lend some. It’s easier to do a room devoted to Fantasia, because I have something more impressive and strong, and Fantasia is, I think for my demonstration, the best example…

AV: The most artistic…

BG: Yes, the most artistic movie, and I think maybe it’s the only really artistic movie that Disney tried to do. Other films are entertainment, but this one was an ambition, of doing something artistic. So that’s the reason why there are two rooms devoted to Fantasia.

And so, as such, the remaining films from the 1940s are more lightly touched upon, with a smaller section devoted to passing the spotlight over Dumbo (1941) and it’s surrealistic Pink Elephants sequence, a literal nod to Bambi (1942) by way of showcasing Rico Lebrun’s wax portrait of the title character’s head from the artists’ drawings, and a slightly larger selection from Cinderella (1950) that dwells on Beatrix Potter’s inspirations for the mice added to Disney’s version of the story.

More mouth-watering is an extensive collection of David Hall’s concept studies for the abandoned 1939 version of Alice In Wonderland, showing just how close the Studio was aiming to emulate John Tenniel’s original book illustrations had the film been made at that time.

Hall was obviously a very busy chap at Disney’s in 1939. Apart from creating over 400 images for Alice, he created a number of paintings for Peter Pan, another feature discarded until later treatment. Ironically, both Alice and Pan were ultimately designed by Mary Blair, and a selection of her work here demonstrates the vast differences between Hall’s very stately, almost Victorian paintings to Blair’s angular, brash and very American late 1940s/early ’50s take.

Thanks to John Canemaker’s excellent Mary Blair book and current issues of the films produced during this period, the art here has been more widely touched upon in recent appraisals of Disney’s work, and this section is perhaps the one most briskly walked through by hardcore fans. This is also due to a leaning towards straight layout and cel set-ups, which means there’s little to compare them to their influences apart from the wonderful The Picture Story Book Of Peter Pan, from 1931, and Iris, a lavish 1886 painting by John Atkinson Grimshaw that clearly highlights the ancestry of Tinker Bell. Since Lady And The Tramp – one of my own personal favourites in terms of the grandly detailed CinemaScope backgrounds – goes unmentioned, it’s down to the lure of Hall’s images for Alice and, another favorite, Pan, that enchant here.

AV: I noticed that later on in the exhibition, there’s more of a reliance on cel setups as opposed to concept art or influences.

BG: We have both, cels and background production, and concept art, especially by David Hall and by Mary Blair.

AV: Ahh, yeah, David Hall’s stuff is incredible. I’ve never seen that in any great detail.

BG: No, nobody has ever seen it before because it was not used for the movie. So it’s completely “new”, but he was a tremendous illustrator.

AV: I was blown away, and by his Peter Pan as well…

BG: He was Irish, and of course he was completely inspired by English illustrations, by fairy paintings.

AV: There’s a lot of Tenniel’s original style in there as well…

BG: Yes! It was directly inspired by Tenniel’s books, of course, the masterpiece of illustration in England. Unfortunately for him it was not used for the film, and Mary Blair was in fact the artistic director. Same thing for Peter Pan, he did a lot of watercolors for Peter Pan. Of course you know that both are masterpieces of English literature, from Lewis Carroll and James Matthew Barrie.

AV: Looking up here at this projected scene, this is one of my favourite shots, of Peter Pan and the children flying over London, and that just there, when the clouds open up and we zoom through; there’s a real rush and you’re almost with them. The illusion of height there is so well created, you could almost fall into that.

BG: Yes, absolutely.

With the 1940s and early 1950s glazed over, I’m hoping for more from the later films, especially Sleeping Beauty, which seems to be a Girveau favorite, but we’re next greeted by a Marc Davis’ pencil test drawing for possibly Disney’s most famous and successful villain, Cruella De Vil, and Bill Peet’s strong, bold character designs for her, based upon the actress Tallulah Bankhead. But being in Dalmatian territory surely means we’ve entered the 1960s? For a second, I’m shaken, until I notice that chronology has been mixed up somewhat for space purposes. Although unfortunately Mary Poppins and The Sword In The Stone have been skipped entirely, we do pass a token cel setup from 1955’s Lady And The Tramp, and naturally it’s from the Tony’s Diner sequence (The Jungle Book is similarly touched on by way of one image in a previous section).

Moving next door, and Sleeping Beauty finally takes the spotlight in her own “chamber”. Another number of cel setups, placed against Eyvind Earle’s backgrounds, hog the spotlight but the highlights here are more of Earle’s inspirational paintings and their source in the form of Briton Rivière’s St George And The Dragon (1908-09).

One thing I spot is that some of the setups look like cel copies that have been cut out and laid on – a Sleeping Beauty frame of the three fairies seems particularly out of place. I put the question of whether the original cels have been cut up, or if these are laser copies, to Bruno…

AV: I saw on some of the setups that you have the original backgrounds and cels that are obviously also original, but then I noticed that not all of them have the directly “painted look” like the excellent shot of Hook in the Peter Pan section. Some of them, as with the Sleeping Beauty fairies here, look like they have they been copied?

BG: Yes. The Archives have chosen to put some cels on background production, but sometimes not the original cel on the background…

AV: But one that works.

BG: Yes, one that could happen. Depending on the Archives, maybe it was thirty years ago they did that, so we have some background production we found without cels, and some with, and some are examples. There is an example upstairs of The Jungle Book, and I was expecting the drawing with King Louie on the throne, and there’s no King Louie! I have the background production, but I need King Louie because it’s the section devoted to anthropomorphism!

Although squeezing in a mention for The AristoCats, the last animated feature to get the direct go ahead from Walt himself before he died in 1966, would have made for interesting inspection on how the Grand Palais would have attempted to work Disney’s own version of Paris into a positive spin, one wonders if this isn’t the precise reason that the line has been drawn here. After all, it’s a natural break off point, and could the French actually accept their own capital city reversioned by way of Disney’s cartoonists? Perhaps a little too close to home! So, with the features under the direct guiding hand of Uncle Walt at an end, we begin to head towards the closing stages now, and perhaps the mot anticipated section yet. I’d known going in that the exhibition would include a showing of the recently completed Destino, but I wasn’t quite expecting the experience that followed!

The originally proposed film was intended to bring Walt Disney together with a “real” artist, Salvador Dalí. Perhaps mindful of the critics that had savaged Fantasia as low art at best, Walt certainly wanted to continue pursuing the use of animation as a true art form. The features of the 1940s went some way towards that, though their popular slant was a way for Disney to appeal commercially to general audiences who had likewise found Fantasia too “highbrow”, and Walt was obviously itching to get more “serious”. On the other side of Hollywood, the celebrated surrealist Dalí was working with Alfred Hitchcock, himself a self-professed Disney fan, on the dream sequence for the director’s Spellbound. Walt heard that the Spaniard was in town, and they eventually met at a dinner party hosted by Jack Warner. Dalí, who on seeing Snow White had proclaimed Disney as “one of the three great American surrealists” alongside the Marx Brothers and Cecil B. DeMille, leapt at the chance of collaborating on their own film.

Dalí spent the next two months at the Studio, and by all reports the two artists got on fine. Destino was originally conceived as an eight-minute short, to be a combination of live-action and animation, but after numerous concept drawings and more than a couple of dozen completed paintings, the project – for reasons unknown – fell through. It wouldn’t be the first or last time Walt would abandon a fairly well developed idea around this time: a similar team-up with Aldous Huxley on another Alice In Wonderland never came to fruition, and a joint-effort between the Studio and British author Roald Dahl resulted in the publishing of a book but not the intended project that sparked the relationship, to be a feature film based on Dahl’s story The Gremlins. Alas, Destino fell by the wayside after an 18 second piece of test footage was completed, and was abandoned after eight months of continued work. Walt moved his attentions on to the greater interests of live-action, special effects filmmaking and, of course, “living” cartoons in the genesis of his theme park aspirations, possibly mindful that he had reached the zenith of what could be feasibly achieved with animation artistically, at least in the direction he had taken it.

Originally as part of a new Fantasia project, Walt’s nephew Roy E Disney took Destino under his wing and attempted a reconstruction of the film with one of the original artists, John Hench, and director Dominique Monfery, using the original recording of the title song, a Mexican ballad by Armando Domínquez, for authenticity. Due to the film’s origins, Disney’s Paris studio was selected for the animation, and work began in May 2001, and completed in 2003 (a nice touch has the closing credits in dual English and French). Some have criticised the film for being nothing more than a way for corporate Disney to finally gain ownership of the Dalí artwork – it was well known that the Studio Archive possessed the imagery but did not own the right to present it until Destino was completed one way or another, such was the contract signed between Dalí and Walt in the 1940s. However, one would like to think that it was an honest and artistically driven initiative, spearheaded by Roy after the title was name-checked in his 2000 continuation of Fantasia. Now, at the Grand Palais, Dalí and Disney find themselves where they belong.

Quite what Walt or Dalí would have actually made of Destino has to go unanswered, of course, since their original intention was never completed. What Monfery and the creators (Hench is given co-writer status) of this short have managed to do, however, is to compose a definitive story through amazing abstract and surrealistic imagery. Set to Domínquez’ ballad (with English lyrics by studio writer Ray Gilbert, and performed by Dora Luz), the short doesn’t sit still for a moment, and despite its artistic aspirations, never feels simply like a bundle of paintings come to life. It’s experimental to say the least, but of the kind of mainstream experimentalism a big studio can afford to do every now and then. Heaven knows what the critics of the time would have thought – coming off the back of the derided Fantasia could have struck a bitter blow to Walt. But, now, we can marvel at this historic achievement – just three years shy of being 50 years in the making.

The style is all Dalí, the fairy tale story (ostensibly about a ballerina who falls for a baseball player and their attempts to meet) all Disney. The movement is exceptional, the result of the CAPS system aiding the animators to create absorbing humans with real, human-like characteristics, but the CGI doesn’t blend as well as it might. Perhaps Dalí’s visual scapes – the Tower Of Bable, the monastery bell tower, the wall where the sands of time slip away, a nightmarish beach and, of course, the trademark eyeballs and melting clocks – are already too rounded and rubbery to be pulled out and about into strange proportions through the CG manipulations. But the Multiplane-styled effects work wonderfully, and ultimately Destino works, almost brilliantly, and, technology aside, it does feel like an old Walt short, principally due to the 1940s audio recording, which really assists in setting it in the period it might originally have been completed. Who knows…if Fantasia had been the artistic and commercial success Walt had envisioned, we might have seen Destino much, much earlier.

As part of Il était une fois, Walt Disney, the Destino short is awarded its own dedicated room, though I found it wasn’t quite shown to its best advantage. Presented in its correct ratio, of course, the projection slightly failed to register in the room, what with the soft lighting creating the mood sparring against the short’s often dark images. The audio, in the interests of not spilling into adjoining rooms, is at a lower than a desirable level, making the lyrics rather elusive to pick out. I’d have much preferred a dedicated screening, or perhaps regular showings in the Grand Palais theatre, which is running a concurrent series of Disney and animation movies in conjunction with the event. Making up for these minor shortcomings is the inclusion, around the room, of 17 of Dalí’s original concept drawings including several paintings, previously unseen, such as the self-explanatory White Telephone And Ruins from 1946.

Although the finished film reflects the tone and style of Dalí’s flamboyant approach to art, it’s clear from these images that he had a far more intricate and very different film in mind – his ballerina, for instance, is much more a classic Disney type here than the modern Esmeralda who dances through the 2003 Destino. Certainly examining the images invites another viewing of the short, upon where many new details can be picked out.

Whatever else, Destino provides Il était une fois, Walt Disney with a more than fitting close. It’s finalisation at the Paris studio completes a full circle that started with Walt receiving the French Medal Of Honor at the beginning of the exhibition and ends with a short that has direct influence from a “reputable artist” in Dalí, and ultimately animated in Paris.

AV: So, in closing with Destino, it really brings things back full circle.

BG: Yes, it’s one of the first times that we can see this version of Destino, made in France, at the Disney Studios in Paris, in 2003.

AV: Yes, and it seems to me to be a very appropriate conclusion.

BG: Yes! You’ve said it.

AV: These Dalí pieces along the walls here are particularly impressive. I found myself watching the short and then looking at the pictures, then watching the short again, and every time you can just see more and more in each.

BG: And you know that some people didn’t realise that there are original paintings by Dalí on the walls? They see the movie and they move on. Destino is so attractive that they miss all this!

AV: I understand it was originally intended in the 1940s as part of another South American picture, like Saludos Amigos or The Three Caballeros, and this new version was, I think, one of four pieces created for a third Fantasia feature, along with other sequences such as Lorenzo, One By One, and The Little Matchgirl, which they just finished and have released as short films in their own right. That next Fantasia hasn’t happened yet, but going back, and I think we touched on this upstairs, but the original Fantasia is about as close to actual animation art, real moving art, that Disney Studios ever got, yet it is often ridiculed by the highbrow art critics as being “crude”. What’s Bruno Girveau’s take on Fantasia, given the technology they had at the time, where without computers to retain the animators’ pure lines they had to ink and paint everything for the cels. How do you think it turned out?

BG: Ahhh, well…I think it’s a very ambitious movie. Not completely perfect, but I think we have to imagine that, even today, who would take the risk of doing such a movie? I mean, to make it…

AV: To make it popular?

BG: Yeah, to make classical music, and contemporary music, popular and bring it to people. It’s amazing. I don’t think that today anybody would do such a movie.

AV: They tried with Fantasia/2000 didn’t they?

BG: Yes, but I think it was not as “good”.

AV: It was maybe too commercial?

BG: Yes, unfortunately. So, it’s imperfect, I mean, its sequences are really different, one from the other, I think the masterpieces are The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, and maybe The Night On Bald Mountain is also is pretty good.

AV: I have to say I like The Rite Of Spring, I know it’s not very popular sometimes, but the whole idea of what they’re doing with that…

BG: It was the most difficult sequence, and it’s not so bad, actually.

AV: With the first animated dinosaurs, apart from Gertie of course, but intentionally done realistically, and again to see that in 1940, you know…

BG: Yes, and it was also inspired by The Lost World movie by Harry Hoyt.

AV: That was animation, with stop-motion.

BG: Yes, the first animation with dinosaurs, quite. It is very impressive.

AV: And there’s, again, the influence of The Rite Of Spring in other later films; in Jurassic Park, the obvious example, there are shots that you can just see Spielberg has used as a direct homage, and that’s fun.

BG: Unfortunately Fantasia was not successful when it was released, but with time, they all became classic, classic movies.

OF INSPIRATION IN CONTEMPORARY WORKS