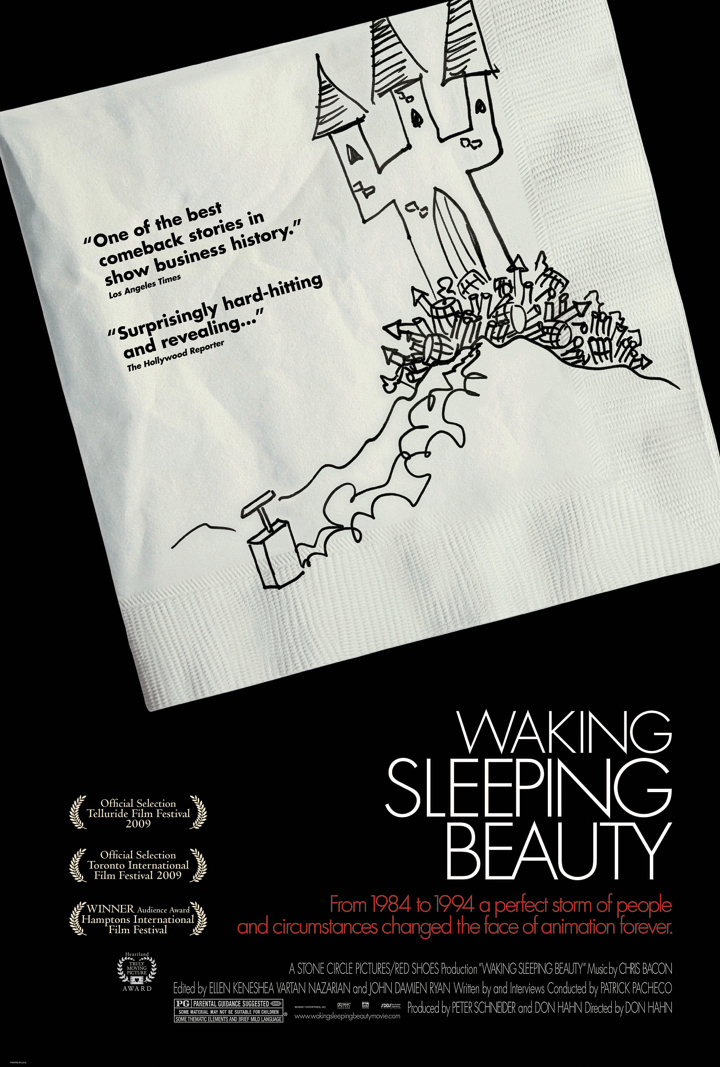

Don Hahn’s refreshingly honest documentary on the “Disney Renaissance” of the 1990s, from its explosion to its explosive downfall, opens today on selected screens in New York, Los Angeles, San Francsico and Chicago. A poster and full press release, in which Hahn describes his film in depth, follows:

circumstances changed the face of animation forever.

Official Selection – 2009 Telluride Film Festival

Official Selection – 2009 Toronto International Film Festival

Winner, Audience Prize – 2009 Hamptons International Film Festival

Winner, Truly Moving Picture Award – 2009 Heartland Film Festival

Stone Circle Pictures

Red Shoes Productions

WAKING SLEEPING BEAUTY (Rated PG)

Directed by Don Hahn

Produced by Peter Schneider, Don Hahn

SYNOPSIS

By the mid-1980s, the fabled animation studios of Walt Disney had fallen on hard times. The artists were polarized between newcomers hungry to innovate and old timers not yet ready to relinquish control. The conditions produced a series of box office flops and pessimistic forecasts: maybe the best days of animation were over. Maybe the public didn’t care. Only a miracle or a magic spell could produce a happy ending.

Waking Sleeping Beauty is no fairy tale. It’s the true story of how Disney regained its magic with a staggering output of hits—The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King and more—over a 10-year period.

Director Don Hahn and producer Peter Schneider bring their insider knowledge to Waking Sleeping Beauty. Hahn was one of the Young Turks at Disney who produced some of its biggest sensations. Schneider led the animation group during this amazing renaissance and later became studio chairman. Their film offers a fascinating and candid perspective of what happened in the creative ranks set against the dynamic tensions among the top leadership, Michael Eisner, Jeffrey Katzenberg and Roy Disney (the nephew of Walt).

The process wasn’t always pretty. The filmmakers bring a refreshing candor in describing ego battles, cost overruns and failed experiments. During times of tension, the animators’ favorite form of release was to draw scathing caricatures of themselves and their bosses. Director Hahn puts several memorable ones on display and marshals a vast array of interviews, home movies, internal memos and unseen footage.

Announcing the world premiere of Waking Sleeping Beauty at the 2009 Toronto International Film Festival, the festival’s documentary programmer Thom Powers said, “Waking Sleeping Beauty celebrates the rich history of Disney animation and honors the many writers, artists and composers who created the Disney magic. The treatment is so thorough that it includes key figures who famously left Disney such as Don Bluth, John Lasseter and Tim Burton. At one time, children imagined that Walt Disney’s signature meant a film was the creation of one man. This is a more grown-up portrayal that reveals the collaborative, often contentious, experience in all its complexity.”

MAKING WAKING SLEEPING BEAUTY

For 10 years, producer Peter Schneider contemplated the idea of making a documentary about the incredibly fertile and turbulent decade that produced some of Disney’s most successful films and revitalized the animation industry. There had been plenty of reporting about this moment in Disney history, but none of it told the complex, riveting story that Schneider had witnessed up close.

“The articles and books that have been written never captured the whole story because they were told from an outsider’s point of view,” says Schneider. “They didn’t capture the joy of a group of creative people firing on all pistons or the unique drama among the key players as they clashed over who would take credit for the renaissance of the animation department.

“Once animation became the ‘heart and soul’ of the company again, everybody started vying for a piece of it,” he says. “Feature Animation was central to the drama.”

Schneider and Don Hahn, the film’s director, were both present during the era they have documented in Waking Sleeping Beauty. “The story parallels the animated films themselves,” Hahn points out. “They’re all about love and conflict. Waking Sleeping Beauty is about the love of a group of people for an art form and the conflict that occurred when that art form became incredibly lucrative and prestigious.”

Both Schneider and Hahn had been deeply involved in the creation of films including The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin and The Lion King. Many years later, they got together. “As with most good films, the idea for this one started in a coffee shop,” says Hahn. “As we sat down with our lattes, we inevitably started talking about our time together at Disney.”

They recalled their years at the studio with mixed emotions of euphoria and horror. They had been part of a team that produced a series of films that were phenomenally successful artistically and financially. “On the other hand, it took its toll,” says Hahn. “And it left us with some incredible Hollywood stories to tell.”

Initially, Hahn was concerned that the story covered too many movies, too many characters and too much time to be told succinctly. “It’s a rich period with some of the most dynamic personalities in the history of entertainment,” he says. “How are you going to capture all that in a 90-minute film?”

But Schneider convinced him that they were in a unique position to tell the real story. “We were in the room,” says Schneider. “We probably knew too much about what happened.”

“But,” adds Hahn, “we thought that if we could tell that story in as honest a way as possible, it would be an amazing tale: Shakespearean characters and palace intrigue mixed with cartoons. Who wouldn’t love that?”

The filmmakers first enlisted the support of Dick Cook, who at that time was chairman of The Walt Disney Studios. He had worked side by side with Schneider and Hahn during those years. “We warned him the film might stray into difficult areas,” says Schneider. “Without hesitation, Dick said ‘Yes.’”

They all felt enough time had passed that the central players on both the artistic and business sides would be willing to speak openly. “It would be at the least cathartic, and possibly an instructional parable for the future,” Hahn says. “Dick recognized that it was a unique time in all of Hollywood—a perfect confluence, as he put it, of executive boldness, artistic excellence and sheer luck.”

Although the film shows the studio in a less than positive light at times, Cook’s backing of the film never wavered. “There were many late nights when I was tearing my hair out trying to tell a tough story,” says Hahn. “I was always wondering if there would be some ‘day of reckoning’ on the film, a day when we would be asked to censor it and edit down some of the more unflattering passages. That day never came.”

The next hurdle was securing the cooperation of Michael Eisner, Roy Disney and Jeffrey Katzenberg. Fifteen years had passed, but they had never before gone on record with their personal memories of that time. “For a long time, it was too raw for them to be able to speak about,” says Schneider. “The biggest surprise for me was how frank everyone was. There was a consensus that the story needed to be told.”

The intervening years had a cooling effect on the former rivals. “At that point, there was no reason for them not to talk about it,” continues Schneider. “No one was feuding. They had each made peace with themselves.”

“In fact,” says Hahn, “Roy Disney was eager to talk. And Jeffrey Katzenberg couldn’t have been more cooperative. Michael was apprehensive at first, but when he saw our approach to the material, we gradually won him over.”

It was unavoidable that the filmmakers, who were so intimately involved in the events they were retelling, would bring their own points of view to the story. “I realized very early that my truth on this topic would not always jibe with Peter’s truth or the truth of the other participants,” says Hahn. “We decided to interview all the players and let them describe their own experiences – their own ‘truth,’ – sort of like 10 blind men describing an elephant. We had some of the best storytellers on earth, why not let them tell their stories in their own words about this insane, creative thrill ride we all lived through.”

To maintain some distance from their material and emotional connection to that period, Schneider suggested that Patrick Pacheco, a veteran journalist who has written for The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times and The Wall Street Journal, conduct the interviews.

“It was important to have someone involved who challenged our assumptions,” Schneider says. “We thought Pacheco could better elicit some provocative material from the interview subjects. So we sent him off with his tape recorder and a list of names. We thought we could capture the story by interviewing 20 people. He interviewed OVER 75.”

“Peter and Don made the contacts and then got out of the way,” says Pacheco. “They made no demands except to tell me that they were looking for an emotional and dramatic story. It became clear early on that Howard Ashman was its poignant heart, not only because of his untimely death but also because of his crucial role. At one point, Roy Disney even compared him to Walt in terms of his influence.”

Pacheco’s interviews uncovered some other surprises for the filmmakers. “Another revelation was the key diplomatic role played by Frank Wells in the delicate balance among Roy, Jeffrey and Michael, something which had never before been explored in accounts of this period,” says Pacheco. “I assumed that Frank’s value to the company was his business acumen. But his talents as a diplomat were just as important—if not more so—to the success of this period.

“It was striking how Roy’s behavior was molded by his innate sense of responsibility, because he alone carried the name Disney and how subtly he was able to wield that power,” says Pacheco. “To my surprise, Jeffrey and Michael were also open in talking about past grievances. It was almost as if they were using the interviews as an opportunity to speak to each other after a long, deep freeze.”

“It’s really a classic Hollywood story in that it reminds us that this town was built by a bunch of ambitious, eccentric and passionate artists, which included Walt Disney and his successors,” says Pacheco.

Waking Sleeping Beauty painstakingly balances the sometimes conflicting points of view of the animation team members and the studio chiefs who competed against each other for control and credit. However, Schneider observes, “It was not us versus them. Sure, the artists can be a subversive lot. Believe me, I took a lot of hits when I first arrived at Disney and they are in the movie. But we all got into the trenches together and that led to a mutual respect.”

And as Eisner says in the film, “Go to any institution, any university, any hospital, any corporation, any home, any house, you know what, the human condition overshadows bricks and mortar, every time. And it’s about fear, and envy, and jealously, and comfort, and love, and hate, and accomplishment. Every institution has it. Were we a bunch of artistic, emotional people running around screaming and crying and ranting and raving? No, it was an organized group of people, working together, saying, let’s put on a show.”

This often contentious collaboration resulted in a “perfect storm” of talent which led to an extraordinary renaissance of the art of animation, which led to artistic recognition, a lot of attention, and incredible box office grosses.

Large egos and infighting are legendary in Hollywood, but much of it usually stays behind closed doors. The power struggle at Disney played out in a uniquely public way and the rumors and reality coming out of the studio transfixed the Industry.

“Disney offered one of the biggest stages on earth for the personalities to surface,” says Hahn. “With success came magazine covers and talk show appearances—and not just for the top brass. Prior to that, the animation industry had been one of the most anonymous professions on earth, not unlike monks copying bibles. Suddenly the artists got their 15 minutes of fame and more. With fame came ego, and with all the good press, it was easy to start believing that you deserved to be in the spotlight. It’s fleeting, as the film shows.”

Prior to 1984, animated films were produced through what Hahn calls “a well-tooled production pipeline.”

“The era from 1984 to 1994 was more akin to a gasoline fire,” says Hahn. “It was a time of high productivity, stressful debate on every creative grain of the movie, and intense pressure to out-do the last accomplishment. It was chaotic, exhausting and thrilling.”

When conceiving the documentary, the filmmakers posted two key rules over the Avid editing system: “No talking heads. No old guys reminiscing.”

”It was Don Hahn who came up with the idea to use only footage that was shot during this 10-year period, with current voiceover,” says Schneider.

“Using only the archival footage from that era was the big breakthrough,” Hahn adds, “I wanted to transport the audience into the rooms where Peter and I sat, into the eye of the storm.

And we were really fortunate because unauthorized photography was always strictly prohibited on the Disney lot, but some of the best and rarest footage comes from animator Randy Cartwright,” Hahn continued. “Cartwright would covertly walk the halls with his cameraman, a young John Lasseter, and film the inner workings of the animation division. This rare glimpse into the studio became the centerpiece of the documentary’s first act.”

“What makes it even funnier is that studio head Ron Miller walks into what is essentially Randy’s opening shot,” says Hahn. “Randy could have been thrown into jail, but thanks to a good-natured Miller, the footage survived.”

Cartwright’s home movies lend immediacy to the story that transports the viewer back in time. “I wanted that voyeuristic feeling of actually walking the hallways and being there in the room,” says Hahn. “We see these guys – Glen Keane, Tim Burton, John Musker, Ron Clements, John Lasseter — operating at the very beginning of their careers.”

Writer Jim Cox shot another round of film during the making of Oliver & Company, this time capturing a young Peter Schneider, Oliver director George Scribner, and some precious footage of the late Vance Gerry and Joe Ranft at work in their story room.

The filmmakers were given access to all the archival vaults at Disney for clips, and discovered another, more unorthodox source for some unique images: Hahn’s mother. She had taped television coverage when the films first came out.

Schneider and Hahn also were able to choose from a rich catalogue of caricatures created by artists for an annual show that was held each year to lampoon them and their bosses. “There were thousands of the funniest, nastiest caricatures imaginable to choose from,” says Hahn, “so the biggest problem was selecting which drawings were best to tell the story.”

Greed, envy, hope, desire, passion, jealousy, fear and love are the stuff of great movies. They also worked behind the scenes of one of the greatest Hollywood dramas in history. “You name it, and it was there,” says Hahn. “We were people with hopes and ambitions who lived with each other as a family in order to make the best movies we could.”

“Making the film was emotional, cathartic and difficult,” says Hahn. “But when I look back, at those years, I do so with equal parts pride, joy, sadness and humility. Pride in what we accomplished together with some paint, pencils, paper and persistence, and sadness at the loss of Howard Ashman, our friend and mentor.”

“I’m humbled to this day by the audience’s reaction to these films, and happy to have been in the right place at the right time to see it all happen,” Hahn continues. “It was a winning season, in every way as exciting and hard fought as any winning season in any sport. And we were lucky to be players.”

“So many people grew up with the movies created during that period,” says Schneider. “This is the story behind those films and it’s a story you can’t get from any other source. In the ‘50s, Walter Cronkite had a series called ‘You Are There.’ Well, it’s Disney, 1984 to 1994. And you are there. I hope the audience will find it as amusing, passionate, emotional and provocative as those years were for Don and myself.”

ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS

Don Hahn (Director) is one of the most successful filmmakers working in Hollywood today. He produced the Disney classic Beauty and the Beast, the first animated film to receive a Best Picture Oscar nomination from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, and to win a Golden Globe for Best Picture. His next film, The Lion King, broke box office records all over the world to become the top-grossing traditionally animated film in Disney history and a long-running blockbuster Broadway musical. Hahn also served as associate producer on the landmark motion picture Who Framed Roger Rabbit (with Amblin’ Entertainment). His other films include The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Atlantis: The Lost Empire and the 2006 short, The Little Matchgirl, which earned Hahn his second Oscar nomination.

He is currently developing the stop-motion animated feature Frankenweenie with director Tim Burton, and directing and producing several documentary projects. Hahn has also authored three books on the art of animation, including the 2008 book, The Alchemy of Animation, which provides the definitive account of how animated films are created in the modern age. Hahn was born in Chicago and studied as a music and art major at Cal State Northridge.

Peter Schneider (Producer) has enjoyed an extensive and multi-faceted movie and theatrical career. His directing credits include the current West End Production of Sister Act, The Musical, The Breakup Notebook, Marc Blitzstein’s opera Regina, Glen Roven’s Norman’s Ark, a revival of Grand Hotel, The Musical, a live action-animation short starring Julie Andrews celebrating the 40th anniversary of Mary Poppins, as well as projects at the WPA Theatre, Playwrights Horizon and Circle Rep.

His Broadway producing credits include the multi-awarding winning The Lion King, for which he won a Tony Award, and Elton John and Tim Rice’s Aida. He is one of the producers of the New York hit Marvelous Wonderettes and the currently running sequel in Los Angeles, Life Could be a Dream. During a 17-year tenure at the Walt Disney Company, where he held several titles including President of Animation and Chairman of the Studio, he was responsible for creating and distributing over 50 movies including The Lion King, Golden Globe Award-Winner Beauty and the Beast, The Little Mermaid, Toy Story, Who Framed Roger Rabbit (with Amblin’ Entertainment) Remember the Titans and The Princess Diaries.

Schneider was the Associate Director of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Arts Festival, is a world champion bridge player, having won the Transnational Open Teams in Estoril, Portugal and received an honorary doctorate from Purdue University. He is married and has two daughters.

Waking Sleeping Beauty, a documentary about Disney Animation from 1984-1994 will be released in the spring of 2010, opening March 26, 2010, in New York, Los Angeles, San Francsico and Chicago.