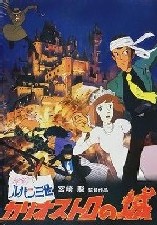

Raz Greenberg looks back on Hayao Miyazaki’s feature animation debut thirty years ago and celebrates The Castle Of Cagliostro, the highly entertaining action adventure movie that remains one of the director’s most unique entries in his filmmaking career.

2009 saw the American release of Ponyo, the tenth feature film of Hayao Miyazaki, and this month also marks the 30th anniversary of the Japanese animation grand-master’s debut film, Lupin III: The Castle Of Cagliostro. Though not as widely-acclaimed as some of Miyazaki’s other works like the children’s fantasy masterpiece My Neighbor Totoro or the Academy Award winner Spirited Away, Cagliostro commands an equally important place in the Miyazaki cannon. The film is a transitional work for Miyazaki in many ways, starting with moving from television work and animation work on other directors’ features into directing theatrical features of his own. Alongside the director’s 26-episode television epic Future Boy Conan, released a year before Cagliostro (and sadly, still unavailable in English-speaking countries), the film defined what a “Miyazaki story” is: from its grandiose action sequences to deeper themes, from hilarious slapstick moments and funny faces to realistically detailed and carefully animated dramatic scenes, the unmistakable touch of a gifted creator was everywhere. With Cagliostro, an auteur was born.

One reason that Cagliostro often gets overlooked in Miyazaki’s filmography is that the film, though a stand-alone work, is also part of an existing franchise – and one that it never seemed to have fully fit in to, alienating both fans and people unfamiliar with the original material. The roots of the franchise date back to the history of modern crime fiction.

In 1905, French writer Maurice Leblanc (pictured above) introduced the character of Arsene Lupin to the genre, and it immediately became a sensation. The stories and novels about Lupin, a thief with a heart of gold who often fights for just causes on the wrong side of the law, are credited with the development of the “Gentleman Thief” archetype in genre books, along with the caper plots that follow the careful planning and execution of a perfect crime. At the height of his popularity, with his slick attitude, and seemingly endless pool of tricks and deceptions, Lupin was the biggest literary rival of another iconic genre hero from across the channel – the cool, logic-driven English detective Sherlock Holmes. Leblanc actually turned this rivalry into a personal affair when he confronted his own hero with an English detective named Herlock Sholmes, a pun obvious to pretty much everyone to this very day.

In 1967, 26 years after Leblanc’s death, Japanese manga (comics) artist Kazuhiko Kato, better known by his pen name Monkey Punch, introduced the character of Arsene Lupin III, the grandson of the famous literary thief. Drawing inspiration from a wide variety of sources – from Leblanc’s original stories through contemporary crime and spy fiction to the satirical graphic style of the American Mad magazine – Kato made his hero, in many ways, in the image of his literary grandfather, but in many other ways, a very different person. Like his grandfather, Kato’s Lupin was the world’s greatest thief, a master of deception that no lawman could rival. However, he didn’t seem to have inherited any of his grandfather’s gentlemanly character. In fact, he seemed to lack any sense of honor whatsoever: backstabbing everyone, friend and foe alike, was a habit for him, either to increase his share of the profit from the current crime he’s involved with or simply for his own sadistic amusement. And though the old-fashioned romantic attitude of Leblanc’s Lupin would probably be considered chauvinistic by today’s standards, he would have undoubtedly rolled in his grave if he witnessed his grandson’s behavior among women – rude, violent, often crossing the line into plain sexual harassment. But Kato kept the general atmosphere of the series light; at their core, the Lupin III stories were played for laughs, and functioned as a satire of sorts on the very anti-social behavior they supposedly promoted.

As noted by Miyazaki himself in his recently translated essays anthology Starting Point: 1979-1996, Kato’s manga was very much a product of its era. In the late 1960s, Japan was still celebrating its amazing post-war economic recovery and prosperity, and Japanese youth of the era found two conflicting sentiments they could identify with in Lupin’s character: they adored him both as a rebel going against a corrupt economic system, but also as someone who could enjoy the good life this system brought with it – good food, fast cars and expensive clothing.

Another sign of the new economic boom was the rise of Japanese animation. Comics became a cheap and accessible form of entertainment in the immediate years following the war, and by the 1960s solidified their status in Japan as content matured along with readers. Like comics, animation existed in Japan long before the war, but the post-war years brought it to prominence: toy manufacturer TOEI began producing high-quality color animated features in the late 1950s, and as television began its massive invasion into Japanese homes in the following decade, studios and productions began to flourish. The country’s comics and animation industries soon began to collaborate, feeding each other’s success. And with the popularity of Lupin III, an animated adaptation of the character seemed like a natural development.

A short animated pilot based on the manga was completed in 1969 by the animation studio Tokyo Movie Shinsha (TMS), with plans to expand it to both film and television productions, but these plans failed to materialize. In 1971, the studio finally managed to get a television series off the ground, but Lupin’s way to becoming an animated franchise was still plagued with many problems. The first team recruited to animate the show tried to follow the adult sensibilities of the original manga – the Lupin III series was one of the first animated shows in Japan made primarily for an adult audience – and the show met with poor ratings. Miyazaki and his long-time partner from his days in TOEI, Isao Takahata, were brought into the production in order to take it in a more action/adventure direction that would appeal to a wider audience, but ratings failed to improve, and when the series ended its run, the prospect of a second season seemed very unlikely.

Miyazaki and Takahata co-directed 14 out of the series’ 23 episodes. As Miyazaki’s earliest credited directing job, these episodes are something of a letdown when compared to his later works – certainly in film, but in television productions as well. There is nothing particularly bad about them, but there is nothing really outstanding about them either. Miyazaki and Takahata did bring a talent for directing kinetic action scenes from the TOEI productions, a talent they now had to implement within a modern-day environment (learning valuable lessons on the design of such environments in the process), and the never-ending battle between Lupin and Inspector Zenigata, the police detective determined to capture him, proved to be as highly entertaining on the TV screen as it did in the comics. But other elements from the comics proved to be harder to translate. Lupin’s gang, consisting of sharpshooter Jigen, swordsman Goemon and femme-fatale Fujiko, proved to be a bland and uninteresting bunch, and scripts often felt uninspired and formulaic: the attempt to appeal to both hard-core fans of the original manga and a wider audience appears to have pushed the show into a lose-lose situation.

Still, a few episodes rose above the general mediocrity. In Hunt Down The Counterfeiter! Lupin competes with another criminal over the services of a retired counterfeiter, who is reluctant to go back to his old line of work. Many of the set pieces of this episode – notably a sequence taking place outside and within the top of a clock-tower – seem to be a general rehearsal for Cagliostro, and the episode also leads to an unusually brutal and tragic climax. Beware The Time Machine!, one of the series’ zaniest episodes and a rare example of a pure science-fiction plot in the show, followed Lupin in his attempts to outsmart a time traveler who promises to make him disappear by killing one of his ancestors. Which Of The Third Generation Will Win? further dug into the Lupin mythology, when it confronted Lupin III with the grandson of Inspector Ganimard, the arch-nemesis of his literary grandfather. Rescue The Tomboy! revealed an unfamiliar and more altruistic side of Lupin III, as he came to the rescue of his father’s partner’s daughter. The episode also featured an exciting train-chase that inspired a similar sequence in Miyazaki’s later film, the magnificent 1986 steampunk epic Castle in the Sky.

Despite the initial lukewarm audience reaction to the series, reruns proved to be quite popular, and in 1978 the franchise returned to life with an animated feature, simply titled Lupin III (released as The Mystery Of Mamo or Secret Of Mamo in English-speaking countries). Directed by Soji Yoshikawa, the film returned to the dark and adult-oriented roots of the original manga, and the big screen proved to be a far more suitable platform for this attitude than the TV screen. The film was a hit, and production immediately went underway to get another film out, as quickly as possible. Miyazaki was offered the director’s chair, and accepted the job. Completed in the insane schedule of just four months, Castle Of Cagliostro was probably a very different film than what the producers and the audience had in mind, but turned out to be a magnificent film nonetheless.

The film opens with both Lupin and Jigen pulling off a successful casino robbery, only to discover that their loot is comprised entirely of forged bills. In an attempt to trace the origin of the forgeries, both arrive at the small European monarchy of Cagliostro, and discover that its sinister ruler, Count Cagliostro, is running a global money-counterfeiting operation. The Count has other plans too – notably, forcing the monarchy’s heiress, young princess Clarisse, to marry him. Can Lupin foil his plans and save the princess?

As the synopsis suggests, Cagliostro presented the audience with a very different Lupin III than the one they knew. With the exception of the robbery at the opening scene, he is portrayed in the film as an almost totally selfless character: his coming to the aid of global economy when the authorities are helpless against the Count’s political power, and his delicate romantic courting of the young princess followed by the tragic realization (on Lupin’s part) that the two just aren’t destined to be together – such behavior was more characteristic of Leblanc’s original Lupin than with Kato’s manga version of his grandson.

Indeed, Leblanc’s Lupin seems to have been a major influence on the film. The characters of Clarice and Count Cagliostro both refer to the twelfth novel in the original Lupin series, The Countess Of Cagliostro (translated to English under the title Memoirs Of Arsene Lupin in the US, and The Candlestick With Seven Branches in the UK). The novel, presented as a prequel to other Lupin stories, featured a young Lupin who is determined to marry his lover Clarice, over her father’s objection to her marrying a commoner. In an attempt to prove himself worthy of Clarice’s hand, Lupin finds himself mixed up in an affair involving Josephine Balsamo, a beautiful woman suspected of being the daughter of the notorious 18th century conman Alessandro Cagliostro. Josephine herself is part of a bigger plot to find an ancient treasure related to Clarice’s family heritage.

The references to these elements from Leblanc’s novel in Cagliostro go beyond the superficial level of names and roles assigned to characters. Miyazaki’s Clarice has something of both the novel’s Clarice and Josephine: Like the novel’s Clarice, she is a gentle, helpless girl, trapped in the tradition of her high-class family. But as the film progresses, much inspired by Lupin, she gains the determination and inner strength of the novel’s Josephine, without acquiring any of the latter’s negative characteristics of greed and jealousy. It seems that Josephine’s darker personality traits have found their way to Fujiko’s character, and yet compared to her behavior in previous incarnations of the franchise, her character’s portrayal in Cagliostro is rather tame. She is also after the treasure, and she causes a lot of mayhem, but unlike Josephine, she does not try to come between Lupin and Clarice – perhaps recognizing a lost battle when she sees it.

Even more interesting is the relationship between the film’s Lupin and his grandfather in Leblanc’s novel. As noted above, The Countess Of Cagliostro was written as a prequel to the other Lupin novels, drawing a portrait of the thieving artist as a young man, with readers fully aware of what this young man will turn out to be. Miyazaki’s film gave the audience an older and experienced Lupin III, one who examines his own past in a rather critical manner, a past that the audience was fully aware of through his previous manga and animation incarnations. Two brief flashback scenes in the film present a young and overconfident Lupin in his failed attempt to rob the Cagliostro family, an attempt that led to his first meeting with a much younger Clarice. In the film’s timeframe, older and wiser, Lupin must succeed where he once failed, now for a noble cause rather than a selfish one. This interpretation of the character may have been a little too radical for its fans, but contrary to some claims, it did not turn Kato’s creation into something different: the film’s Lupin is very much the same character from the previous manga and animation incarnations – he just grew up.

The regular cast of supporting characters also seems to have matured in the film. In the TV series, Jigen and Goemon’s main function was to be sidekicks for Lupin, tools in the execution of his plots. In Cagliostro they became something more akin to friends and confidants, who – not unlike Lupin himself – realize that there are things worth fighting for other than their greedy ambitions. In the course of the film, even Inspector Zenigata learns to respect Lupin, putting aside his own obsession with the thief’s capture and realizing that there are greater dangers and evils in the world, ones that only people like Lupin can truly struggle with.

These changes are also reflected in the film’s design. While the character design for the TV series kept the original manga style of twisted and exaggerated features inspired by Mad magazine, the characters of Cagliostro have a more streamlined, cleaner look, closer to the clear-line style of Franco-Belgian comics. The gorgeous, colorful, pseudo-European scenery in which the film takes place was doubtlessly inspired by Miyazaki’s own travels: in the decade that predated the production of Cagliostro, he made many trips to the old continent, making landscape sketches for animated adaptations of classic children’s literary works such as Johanna Spyri’s Heidi and Edmondo De Amicis’ From The Apennines To The Andes. Yet the main European influence on Cagliostro came not from the real world, but from an earlier animated masterpiece.

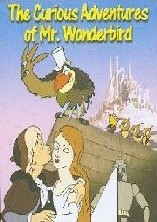

From a very early stage in his career, Miyazaki has admired Paul Grimault’s animated feature, La bergére et le ramoneur (The Shepherdess And The Chimney Sweep). Loosely adapted from a fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen, the film followed two young lovers who must run away from a pompous, evil King determined to marry the Shepherdess. The film’s production proved to be a nightmare for Grimault, and it was initially released against the director’s wishes in an unfinished form in 1952.

But even unfinished, the film’s beautiful visuals captured the hearts of many animators worldwide – especially, it seems, at TOEI, where Miyazaki had worked for the better part of the first decade of his career. In 1969, Miyazaki was one of the animators working on the studio’s version of Puss ‘n Boots, based Charles Perrault’s classic tale but actually more closely modeled after Grimault’s film: the relationship between the boy-protagonist Pierre and the sharp-tongue cat Pero strongly resembled those between the young Chimney Sweep and the wise Mockingbird in Grimault’s film. Other elements in Puss ‘n Boots echo Grimault’s film, especially a scene in which Pierre and Pero disrupt a planned wedding between the evil demon and a helpless princess. In Puss ‘n Boots, this scene leads to the film’s climatic chase sequence, animated by Miyazaki and largely considered as a prototype for the climatic sequence of Cagliostro.

Cagliostro also borrowed many narrative and visual elements from Grimault’s film: the basic plotline of disrupting the wedding of an evil tyrant and a beautiful innocent girl, the tyrant’s luxuriously-decorated palace that is also full of traps, and a gang of henchmen serving the tyrant – both oversized goons and ninja-like assassins (in one of the most delightful scenes in Cagliostro, the assassins’ masks come off – revealing a bunch of embarrassed, middle-aged people). The film’s portrayal of Lupin himself seems to combine both the delicate romanticism of the Chimney Sweep and the Mockingbird’s talent for mischief. Fujiko’s character has inherited some of the Mockingbird’s traits as well – particularly toward the end of the film, when she takes over a TV news report in a manner very similar to the narration provided by the Mockingbird toward the end of Grimault’s film.

As with Leblanc’s original novel, Miyazaki’s references to Grimault’s film show a deeper understanding of it beyond the surface-level visual and narrative elements. Grimault used height and depth as metaphors: the evil king in his film lives in the top floor of the high tower of his palace, ruling over a kingdom of beautifully-designed buildings and monuments, though its streets are eerily-empty, thinly-populated by his servants. Only underneath this kingdom, underground, live the common folk in poverty, without even the privilege of sunlight. The castle of Count Cagliostro is a similarly extravagant monument of architecture, built on the foundations of evil – the forgery operation that has been running underneath it for years, fueled not only by the Cagliostro family greed, but also by the collaboration of the nations that supported it. If Grimault presented the struggle for freedom as the struggle of the people against the tyrant, Miyazaki reminded his audience that this struggle should take place on a global, rather than personal or even national level. In an interesting coincidence, shortly after the theatrical debut of Cagliostro, Graimault won his own personal struggle for freedom: in 1980, he finally managed to complete and release his film the way he meant for it to be seen, under the new title Le Roi el lóiseau (The King And The Bird).

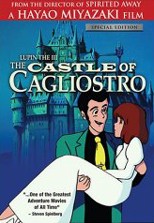

Miyazaki’s interpretation of Lupin’s character resulted in a wonderful film, but unfortunately it also proved to be a bit too different for fans of the franchise, and upon its initial release in Japan, Cagliostro was considered a box-office disappointment. Outside Japan, however, where most spectators were unaware of the character’s history and background, the reaction was very different. For the non-Japanese audience who experienced a Lupin story (and Miyazaki’s direction) for the first time through Cagliostro, the film presented some of the most incredible action scenes ever seen, in and outside of animation. The early car-chase, the dangerous escape from the castle, and the climatic clock-tower sequence left viewers with their jaws dropped. Rumor has it that Steven Spielberg himself praised Cagliostro as adventure filmmaking at its finest (this rumor has never been confirmed, but it didn’t stop at least one American DVD release from carrying the supposed Spielberg quote on its back cover).

Another major figure in the American entertainment industry upon whom Cagliostro made a very deep impression is John Lasseter. In the early ’80s, Lasseter was a young animator at Disney, unhappy with the studio’s generic productions at the time. It was the discovery of Cagliostro that demonstrated to Lasseter what animation can really do, and what kind of films he wanted to make himself. Lasseter went on to become the creative leader of the computer animation studio Pixar, and his admiration for Miyazaki turned into a personal friendship between the two. Lasseter has declared that Miyazaki’s movies are an important source of inspiration for the Pixar animators.

Other young rising stars at Disney appear to have also been inspired by Miyazaki’s debut feature. John Musker, Lasseter’s classmate in CalArts and a prominent figure in Disney’s later renaissance of the late ’80s and early-to-mid ’90s (directing The Little Mermaid and Aladdin) paid homage to the climatic clock-tower sequence of Cagliostro in his 1986 feature directorial debut, The Great Mouse Detective. Homage to the aftermath of the same sequence, spiced with a look inspired by Castle In The Sky was also paid in Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise’s 2001 adventure, Atlantis: The Lost Empire.

Cagliostro and Miyazaki’s work in general were also an important source of inspiration for a team of young animators at the Warner Brothers Studio as they embarked on a journey to re-invent superhero animation at the early ’90s. Batman: The Animated Series and its many sequels and spin-offs set new standards for dark, sophisticated storytelling in American TV animation, and the animators working on them were quick to recognize Japanese animation as a rich source for ideas. An extended homage to Cagliostro was paid in the climactic sequence of The Clock King, one of the early episodes in Batman: The Animated Series, with a more brief reference also made in Mask Of The Phantasm, the first feature in the animated Batman franchise. The production of Mask Of The Phantasm also closed a cycle of sorts, when it employed the services of Yukio Suzuki, a Japanese animator who started his career as an in-betweener in Cagliostro – he would go on to direct episodes of Batman Beyond, the spectacular futuristic take on Batman’s character.

Back in Japan, it turned out that the box-office performance of Cagliostro did not spell the end of the Lupin III franchise, or Miyazaki’s involvement in it. In 1980, a new TV series starring Lupin debuted in Japan, becoming a hit and spreading across no fewer than 155 episodes. Toward the end of the series’ run, Miyazaki was brought in to direct two episodes – Albatross, Wings Of Death and Farewell Beloved Lupin. After Cagliostro, Miyazaki was obviously thinking big in terms of direction, and both episodes feel as though they could have been a part of some big-screen action spectacle. Sadly, they had problems fitting within the short timeframe of a standard television episode.

Albatross, Wings Of Death pits Lupin against an evil scientist armed with nuclear bombs onboard an airplane, holding Fujiko as a hostage. With its paper-thin plot, the episode is essentially a non-stop action affair, which could have worked better as part of a larger narrative. As it is, Albatross, Wings Of Death is entertaining but forgettable, with the main attraction being the exciting sky chase (Miyazaki’s specialty) and the design of the evil scientist character – a design that Miyazaki would re-use for two more sympathetic characters: the old airship mechanic in Castle In The Sky, and boiler-room operator Kamaji in Spirited Away.

In Farewell Beloved Lupin, a series of daring crimes is performed by a giant robot, and suspicion falls on Lupin’s gang as the responsible party. The government, meanwhile, seems happy to exploit the situation by enforcing martial law. The episode features well-crafted action scenes, inspired by the classic Fleischer brothers’ 1941 Superman cartoon Mechanical Monsters (the jewel-robbery scene that opens the episode is an almost shot-for-shot recreation of a similar scene from the Fleischers’ film), and its political message against the abuse of government power gives the narrative a feeling of depth that Albatross, Wings of Death had lacked. But the episode still proved a bit too ambitious for its own scope: things get resolved too quickly, and the twist about the villain’s (and hero’s) true identity feels forced.

In 1984, Miyazaki’s theatrical adaptation of his own manga Nausicaa Of The Valley Of The Wind debuted, becoming his second feature. The film was a success, led to the foundation of Miyazaki’s animation studio Ghibli, and effectively ended his long career on TV productions. But shortly before that happened, in the last small-screen production to involve Miyazaki, he managed to give Lupin III a final bow by adapting the stories of his grandfather’s greatest literary rival.

In 1981, Miyazaki wrote and directed six episodes in the Japanese-Italian co-production Meitantei Holmes (Famous Detective Holmes), an animated adaptation of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, in which the entire cast was presented as anthropomorphic dogs (the series is titled Sherlock Hound in its American release). More action-oriented compared to Doyle’s mystery-solving plots, the series nonetheless provided highly entertaining weekly thrill-rides, set against beautiful backgrounds designed in Victorian style, with light touches of steampunk technology.

The first three Sherlock Hound episodes directed by Miyazaki are particularly fascinating, as they appear to be a direct continuation – in both narrative and concept – of his work on the Lupin franchise. In A Small Client, Holmes is approached by a little girl (whose design is somewhat similar to Mei, the young protagonist of Miyazaki’s later film My Neighbor Totoro), asking him to find her missing cat. The first part of the episode contains a terrific scene in which Holmes decodes an encrypted message, a task that reminds the audience of his literary origins. The second part of the episode leads to an action-packed climatic confrontation between Holmes and his arch-nemesis Moriarty, in an attempt to stop the latter’s plot to flood England with forged coins – an obvious reference to Cagliostro.

In Miyazaki’s next episode, Mrs. Hudson Is Taken Hostage, Holmes’ housekeeper is kidnapped by Moriarty, in an attempt to extort Holmes into stealing the Mona Lisa from the London National Gallery (loaned by the Louvre, one assumes). The episode plays almost like a piece of fan-fiction: what would Holmes do if he found himself in Lupin’s shoes? The setup for the episode’s robbery scene, which includes a classic Lupin-style threatening letter sent to the police, an angry Inspector Lestrade who could double for Zenigata, and a clever deception, all add up to a highly entertaining story, which becomes even more entertaining with the added value of the scenes portraying Moriarty and his henchmen as they attempt to deal with their hostage.

The third Miyazaki episode, The Blue Ruby – a name that alludes to the literary Holmes mystery, The Adventure Of The Blue Carbuncle, though largely unrelated to it otherwise – opens with Moriarty pulling a clever Lupin-like stunt of his own, when he creates a large-scale diversion in order to steal a precious gemstone. But shortly afterwards he loses it to a young, resourceful pickpocket girl – who soon must rely on Holmes to pull herself out of trouble. Much like Miyazaki’s work on the Lupin franchise, this episode carries the sentiment that not all thieves are bad people. Miyazaki directed three more episodes in the show, notably The White Cliffs Of Dover, which introduced many elements that would form his 1993 feature Porco Rosso. Licensing problems delayed the broadcast of the show until 1984 – the same year that marked Miyazaki’s final move to theatrical features.

Miyazaki’s work on the Lupin franchise, leading from television to film and back, represents a fascinating stage of his career, one that shaped his skills as an animator and storyteller, and set him on the path to becoming one of the world’s most admired animators.

While writing this article, I have consulted several sources highly recommended for anyone who wishes to know more about Miyazaki and Lupin III. Helen McCarthy’s book “Hayao Miyazaki, Master of Japanese Animation: Films, Themes, Artistry” remains, ten years after its initial publication, the best introduction to the world of Miyazaki and his films. On the Internet, Nausicaa.net is the definitive Miyazaki resource, and the Lupin III Encyclopedia is the place to learn everything one wants to know about the Lupin III franchise. Finally, a highly informative and entertaining commentary-track for “Castle of Cagliostro” has been recorded by Chris Meadows, and is available for download at his blog. Listening to it makes repeated viewings of the film a very rewarding experience.